Harm Was Done: Subversive Sympathy in Anakana Schofield’s MARTIN JOHN

In her second book, a kind of footnote to her debut novel Malarky, Anakana Schofield presents us with Martin John, a sexual offender hiding out in London having fled the West of Ireland. Told by a corrupt, collective chorus, the novel details Martin John’s compulsive, constrained psychology as well as that of his mother and, for a few devastating pages, one of his victims. Where does Martin John sit in relation to such works as Nabokov’s Lolita and A.M. Homes’ The End of Alice, and what role do such works serve?

Martin John is not always an easy book to read, partly because Martin John’s is not an easy consciousness to inhabit, and partly because he’s a sexual deviant. Originally from the West of Ireland, where he’s assaulted multiple girls and women as well as one man, which proves too much for his mother, Martin John has been sent to hide out in London.

The book is primarily told from the displaced perspective of the voices inside his head–a corrupt, unfeeling kind of chorus. Seeing Martin John, amongst other things, ejaculate on an unconscious woman, I wondered at the novel’s being heralded as “a brave book to write,” untouched by charges of crass gratuity that have befallen, to varied degree, such novels as A.M. Homes’ The End of Alice and Nabokov’s Lolita (Homes and Nabokov’s narrators are of course paedophiles, which Martin John is not, though he assaults children while still a child himself).

In the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani describes The End of Alice as “a . . . single-minded pursuit of sensationalism . . .” It’s true that the book graphically hypothesizes how criminals such as Chappy, an imprisoned paedophile, come into the world. While still a child, for instance, he is made to insert his fist inside his mother. She orgasms, and he believes he’s killed her.

Kakutani also writes of Lolita,

. . . the novel was less a tale about a middle-aged man’s lust for a 12-year-old girl than an astonishingly layered meditation on language, literary conventions and the American myths of innocence and the retrievable past.

The dismissal of Alice seems too easy, the praise for Lolita too myopic. Lolita is, of course, all the things Kakutani describes, but it is also a tale about a middle man’s aged lust for a twelve-year-old girl, also a tale about how he rapes her, samples her “brown flower” “which tasted of blood.” Mishka Hoosen recently reflected on her enjoyment of Lolita being tinged with “something like a little hand on my sleeve . . .” While Alice might not be a masterpiece, might indeed be sensationalist, Lolita has also left more than one reader with the suspicion that, despite its artistry, it sees the female body quite badly used.

Where, then, do we place Martin John?

Similarly to Homes’ Chappy and Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert, Martin John is beyond redemption–is entirely immersed in his pathology. He is, however, without the capacity for self-reflection or insight. He is not an intellectual or aesthete. He is not charming. He is enslaved to actions he does not understand, and his inner life is one of cyclical constraint:

Who knew? He knew. He knows he knew but did you know?

His mother ties him to a chair before she goes to work.

He scalds his own genitals with boiling water.

He puts off showering for as long as possible, and holds his bladder to the point of bursting in an infantile attempt to feel something akin to sexual pleasure.

And so, while we will not forgive him his actions, can we truly hold them against him? Can we blame him?

This line of reasoning is shattered by a few devastating pages in the final quarter of the book:

SHE

Remembers

How

He crawled across the carpet on his knees . .

. . .

He didn’t speak a word.

It hurt.

. . .

She roared.

. . .

Today, a 32-year-old mum . . . she was still living with it.

. . .

The pain revisits her like a phantom limb. Never quite gone.

A female body is harmed, but the female body also speaks its hurt, and the shock of the encounter induces a sharp realisation in the reader. Her trauma sees our compassion displaced, our sympathy subverted: we have fallen prey to the rationale that sees troubled boys become troubled men who then cause trouble for girls and women.

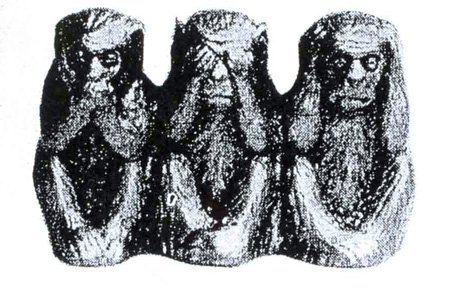

All three novels insist we look, but only Schofield does so with a mind to illuminate the insidious infrastructures which hold up gendered, sexual violence. Schofield, herself Irish-Canadian, does an especially excellent job with the nuances of Irish repression, its culture of things gone unspoken, unheard, unseen. A culture whose subliminal conditioning renders it incapable of speaking the harm done to women.

So, while all novels posit fiction as an interrogative force, an art form that obliges us to look where we would rather not, Schofield does something more with our rapt attention, something that reaches beyond “layered meditation” and virtuosic phrase, perhaps beyond the scope of the novel itself. Martin John, in short, justifies its portrayal of harmed, traumatised bodies in a way Alice and, yes, perhaps even Lolita does not.