Heather Christle’s Portrait of Crying

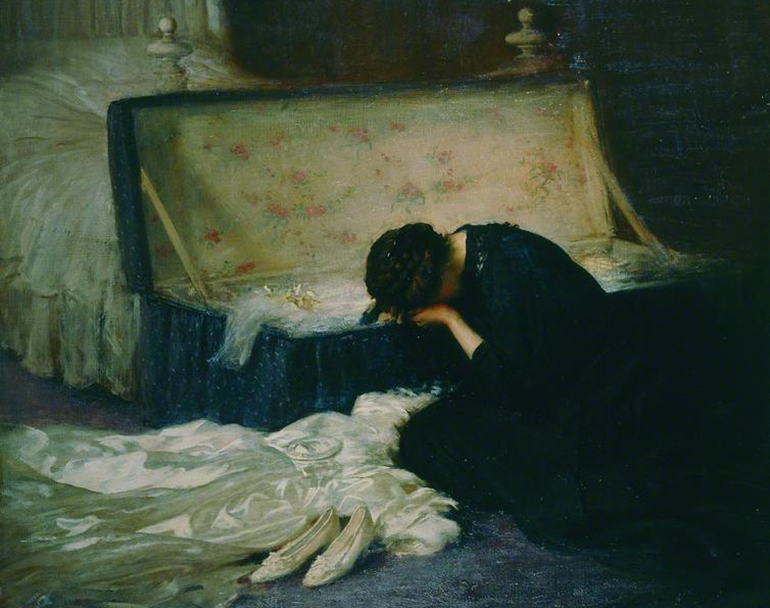

Recently, while taking my dog on a routine visit to the vet, I saw a woman crying. She sat curled in the corner of the large waiting room, a fluffy red dog bed lying empty beside her. Her tears were restrained, not performative. Occasionally she would dab at her eyes with a crumpled Kleenex. I wondered about her situation, theorizing that it most likely involved the death of a beloved pet, though while I waited for the technician to bring my dog out to me, I felt paralyzed. Here was a woman clearly in distress and everyone around her was doing their best to stare anywhere but at her. “To cry with more people present, concludes the International Study of Adult Crying, can lead to a worsening mood, though that may depend on others’ reactions,” states Heather Christle in The Crying Book (2019). The waiting room that day was full of patients. As this woman wept, was our immense and looming presence only worsening her pain?

The Crying Book is a unique account of all the ways and reasons a person can cry. Made up of fragments that each attempt to convey something specific about the act of crying, the book is a lyric exploration of this uniquely human way of performing grief. Threaded throughout her fragments are Christle’s own experiences with loss—she meditates frequently on the death of her beloved friend Bill—and her inclination to experience long bouts of weeping. The result is a beautiful study of one of humanity’s most universal experiences, the fragments acting as tear drops that, when collected, turn the book into one very good, very emotional cry.

At the beginning of every good cry, there is restraint. Even if you want to give in to the tears, often the body resists. After all, who wants to be sad? Sometimes, a person resists the tears because it is not the right time or place to shed them. Other times, tears are held back out of shame or embarrassment or an attempt to appear strong. Whatever the reason, tears do not always flow readily. At the start of The Crying Book, Christle is careful to note this restraint. She turns to Ovid, who she notes “would prefer that I and other women restrain ourselves.” And it’s true. He wants women to “be comely” with their weeping and “learn how to turn on the tears still keeping proper control” because to give in to the act would simply do nothing more than create a spectacle of yourself.

But just as soon as she warns us to exercise restraint when faced with the possibility of shedding tears, she gives us plenty of reasons to weep. There is the time she “was unexpectedly dumped in public” and ended up crying in her car. Other times she has cried over beautiful literature and the prospect of having a child. “Motherhood gets me,” she writes. “I cry whenever I watch a representation—whether fictional or no—of birth.” Tears come after she learns of the sudden death of her friend, and they come when her sister moves away to Maine. She cites the Kent State massacre as a day riddled with tears, and she meditates on a young artist’s invention of a tear-shooting gun designed “after a demanding professor made her cry.” The world is filled with reasons to cry, and Christle gifts each of them their own fragment, single instances of sorrow that pool together to create an onslaught of tears collected on the page.

She is careful, though, to note that crying can also be insincere. She says, “We scrutinize the tears of other people for their sincerity. We can even doubt the sincerity of our own.” It is here in these fragments where Christle, a white woman, carefully considers her role as a woman with the power to cry. She notes that “white women are subject to specific scrutiny, because their weaponization has so often meant violence toward people of color, and black people in particular.” Her instinct to doubt the crier, especially so early in the book, is evocative of everyone’s doubt (even that of the self) when initially faced with a person in tears. Always there are two things: a wish to make the crying stop and a curiosity about whether the tears are truly genuine.

If a person is crying and they are sincere, eventually their crying will peak. Christle refers to this state as “the fog of despair,” and there are many things that can bring about this particular emotional release. Christle’s fog consists of motherhood and the moon. She provides us with fragments about each, evoking both the tenderness and the sorrow a person feels at the height of a good cry. These instances predominantly occur in the book’s middle, in which her fragments are filled with an outpouring of raw emotion. She turns to Margery Kempe as a figure for the constant state of weeping one achieves in the midst of a cry. Kempe is known as “the English medieval mystic famous for her near-constant weeping,” and Christle draws meaning from this woman’s sorrow, sighting her “ecstatic tears” alongside those of her one-week-old baby, who “will not stop crying.” Once a person has begun to cry, sometimes there is no stopping it.

One of the most beautiful things Christle does with her lyrical fragments is use them to create sorrow in moments that might at first seem to lack it. In one fragment she writes, “At the end of the week, on my birthday, I will fly down to Florida with the baby for my American grandmother’s funeral. Last night I wrote a list of what to pack: the rubber giraffe, a sun hat, waterproof mascara. This will be the baby’s first time to see the ocean.” Here, the grief lies in the death of Christle’s grandmother, and yet the true sorrow is felt somehow in the image of that rubber giraffe, that sun hat, that mascara, that mention of firsts. But this sorrow remains amorphous, even though it looms large on the page, and it isn’t until she follows it with a second fragment that the sorrow makes sense: “It was when fish became terrestrial amphibians that the body’s lacrimal system first evolved. We left the water and began to weep the home we’d abandoned,” she writes. And so, the baby traveling to the beach for the first time becomes a symbol of evolution. In order for her daughter to gain new experience, she must grow up and leave the comforts of her home—a process that, much like the “terrestrial amphibians,” may make her weep. The result of these fragments is devastating. Tears well in our eyes. We are right there with Christle in the fog of despair.

To evoke the despair of a good cry, Christle turns to Virginia Woolf, often referred to as a woman in despair. Christle dedicates a fragment to thinking about Woolf’s death, wondering if, at the time of her suicide, Woolf “thought rocks or stones?” This imagining evokes the specificity of grief, how it can only be summed up by a person’s own experience, and she uses Woolf as a springboard into her familiarity with despair. Christle writes, “I am not going to be able to perform the acts known as making dinner because I am in despair.” Her despair becomes palpable, a thing that inhibits her from performing basic daily tasks, and we understand that despair is part and parcel to the act of crying. But just as soon as we pair the emotion with the person, Christle separates us from it so that all we are left with is the rawness of the despair itself. “Despair recognizes its own ridiculousness, its emotional exaggeration,” she writes. “It makes no space for shallows.”

So what is one to do when faced with the troubling middleness of despair when crying? How can one climb out of the sorrow and stop the tears? Christle turns her fragments toward empathy. “Perhaps it would be truest to allow two stories to correspond briefly, to align themselves into one moment as they travel separate orbits,” she writes. Here I can’t help but be reminded of myself—the reader—and Christle “aligning ourselves” and our own experiences with crying so that we might better understand one another. Though we are strangers, we share the ability to relate to each other, and if we choose to do so in moments of despair, we might be able to lift one another out of the wreckage of our tears. Christle follows the above fragment with: “When I am not in despair I can barely even describe it. It is a trap door in my life. A bridge to nowhere. It is only a metaphor, a line. But one I send my love across.” The anguish of the good cry has been breached, but only after we have found empathy in another.

The book ends with Christle giving a talk on craft to a group of students. Before she leaves for the talk, she “pause[s her] crying.” The final fragments of the book are made up of Christle and this community of other writers. Together, they reflect on writing, and she asks one of them to recite a poem. One of the poets volunteers, “walks to the corner of the room, and switches the lights rapidly on and off.” The people in the room sit amidst the flashing. Much like crying and much like the fragments that make up The Crying Book, they are repeatedly brought in and out of the darkness together. But just like our actions can cause others to cry, it is also the other’s hands that can flip the switch of our darkness and bring us back into the light.

This piece was originally published on September 29, 2022.

About Author

Miyako Pleines is a Japanese-German American writer living in the suburbs of Chicago. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Northwestern University. Her work has appeared in Hypertext Review, Hapa Mag, 1966: A Journal of Creative Nonfiction, and is forthcoming from the Sierra Nevada Review. She writes a monthly column about birds and books for the Chicago Audubon Society, and she can be found on Instagram @literary_miyako.