Hillary Clinton, The Orator, and the Body

In her book What Happened, Hillary Clinton gives some thought to the exaggerated focus on her appearance during the presidential race. Rather than give serious attention to her ideas and views, the media had a field day parsing out her outfits, her hair, and her makeup. She speaks of the public’s obsession with her looks with a tone of resignation. This is the world we live in, she says, and so she got with the program.

In her book What Happened, Hillary Clinton gives some thought to the exaggerated focus on her appearance during the presidential race. Rather than give serious attention to her ideas and views, the media had a field day parsing out her outfits, her hair, and her makeup. She speaks of the public’s obsession with her looks with a tone of resignation. This is the world we live in, she says, and so she got with the program.

Reading this, I felt at once both furious and forlorn. I could imagine that, in her place, I would have jumped through the same hoops, making every possible effort in order to give commentators only positive things to say. But I also wished she’d been angrier; that she’d gone out of her way to not give them something to talk about. I’m no Hillary Clinton, and yet it is shocking and heartbreaking each time I confront the fact that both of us are little more than a piece of ass.

In theme with my political reading, I also recently read The Orator, a new Hebrew novel by Israeli writer Magi Otsri about politics, social justice, and racial tensions in Israel. It is focused on women, revolving around the dynamic between a female reporter, a groundbreaking underdog Mizrahi female politician, and the daughter the politician gave up for adoption. I found this book incredibly relevant to our current culture of awakening—regarding both the casual ignorance of racism and sexism, as well as the power of the media and the resulting cults of personality around celebrities. It is also an intoxicating exploration of women between the ages of twenty and fifty, the ways they see the world and build it with every choice they make, and the different ways in which they bleed.

In a particularly poignant scene that inspired the same kind of mixture of fury and grief, the adopted daughter asks the reporter about her military service on an air force base. The reporter launches into an interior monologue regarding the racial divide between the Ashkenazi pilots and Mizrahi technicians; the hierarchy in which the pilots ate their meals first and their female secretaries and administrators were left to share the scraps. Most vividly, she recalls how trapped the women on base felt, each of them assigned either to sexually pleasuring the male pilots or to being an invisible wannabe; all of them fantasizing about receiving validation in the form of a pilot boyfriend, only to go to sleep, aroused and alone, in their army beds while the men were on mission or partying on leave. She recollects crying in the bathroom when she overheard the pilots in her unit complaining to her commander about how unsexy she was, staying locked in the stall for hours, staring at a doodle of a penis, the likes of which she’d never seen in real life. Too mortified to reveal to the young woman just how humiliated she felt at not even being considered good enough to become a sex toy, a disposable object, the reporter simply answers, “It was boring.”

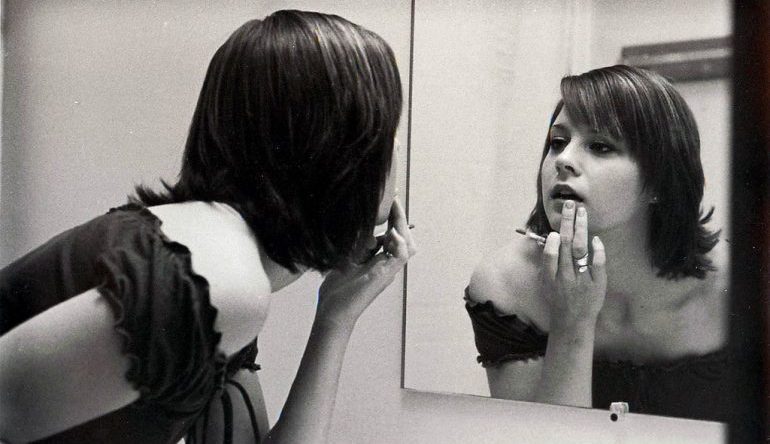

And, honestly, it is boring. Whenever I spend the day obsessing about my weight, or my haircut, or my skin, or why I chose to wear the jeans that make my ass look big (or whether a big ass is actually a good thing), I return in my mind to Zadie Smith’s interview with The Times that made waves some months ago, in which she reported limiting the time her daughter spent doing her makeup in the morning. She told her, “Your brother is not going to waste any time doing this. Every day of his life he will put a shirt on, he’s out the door and he doesn’t give a shit if you waste an hour and a half doing your makeup.” Of course, much of the reaction to this core-shaking statement had to do with Smith’s own natural beauty. We’re trapped.

We’re trapped because we haven’t found a sufficient alternative to being judged by the way we look. This week, I overheard a man arguing that I must be pregnant, and another recommended a new diet pill to me. I believe these comments had less to do with how fat I seemed to them, and more because they are men and I’m a woman, and if my body doesn’t conform fully to expectation I must either be going through something, or looking to change it. People look at our bodies first, and for a long time. Our minds aren’t seen as nearly as important. We’ve been taught this, and now we’re stuck. And so, when women seek validation, we look to our appearance, and how others perceive it.

I don’t wear makeup. I usually decide on an outfit during a seven-minute shower. The longest hair care routine I ever had took less than ten minutes to perform. And yet, even though relatively little of my time is dedicated to my appearance, an obscene percentage of my mind and energy are devoted to thinking about the way I look, trying to guess how others see me, and thinking and rethinking that afternoon cookie (which, really, we all know I’m going to have). When I put together an outfit I think looks cute, I feel more confident. When I get a good haircut, life seems to make sense. These illusions shatter within minutes, of course, but string enough of them together, and you might just be able to fool yourself into thinking this shit is more than just a means of keeping women in their place.

The women in The Orator—while accomplished and ambitious in their own ways—all pay a price for their bodies and what they do with them. From repeated romantic rejections to obsessive visits to the gynecologist; from unwanted pregnancies to forced sexual relationships, none of them has the pleasure of simply living in her body. Being thus troubled, it is sometimes amazing to think they—we—can get anything done at all.

Both Hilary Clinton and the fictional women in The Orator are in search of a new metric, one that doesn’t reduce us to whether or not we lost the baby weight, magically avoided wrinkles, or bought the right kind of pants. One that doesn’t wait for us to prove beyond all doubt that our minds are superior before it can even consider absolving us of the imperfections of our female bodies. Only when the protagonists of The Orator are able to shift the focus away from their bodies and sexual pasts can they begin to attain the kind of success they dream of. For Hilary Clinton, the pill was much more bitter—not for lack of trying. I don’t know if the world will ever give us a break, but I can say that, for my part, I intend to do everything I can to carry my body as comfortably and mindlessly as I can in the world, and focus instead on what I, and other women, create.