How Should A Writer Be?

Yesterday on the bus I sat behind a woman whose toddler was having a Richter-ten tantrum concerning his left shoe. He flung himself out of his seat, flailed his arms, pulled his mother’s hair, and wept into his shirt because he didn’t want to wear his shoe. This lasted for at least twenty blocks, and his mother remained perfectly calm. Never mind that the entire bus was watching, never mind that her son’s shrieks in her ear must have been pushing her dangerously close to a migraine, she kept her voice low and level, held onto him enough to keep him safe, and eventually got the shoe on. As soon as the Velcro was Velcroed she scooped her son into her lap, where he immediately fell asleep. You, I wanted to tell her, are a saint. You are a genius of patience. But I also thought as I watched her: What if this woman is a writer? Is her day shot? How can she ever get anything done? How do writers have kids?

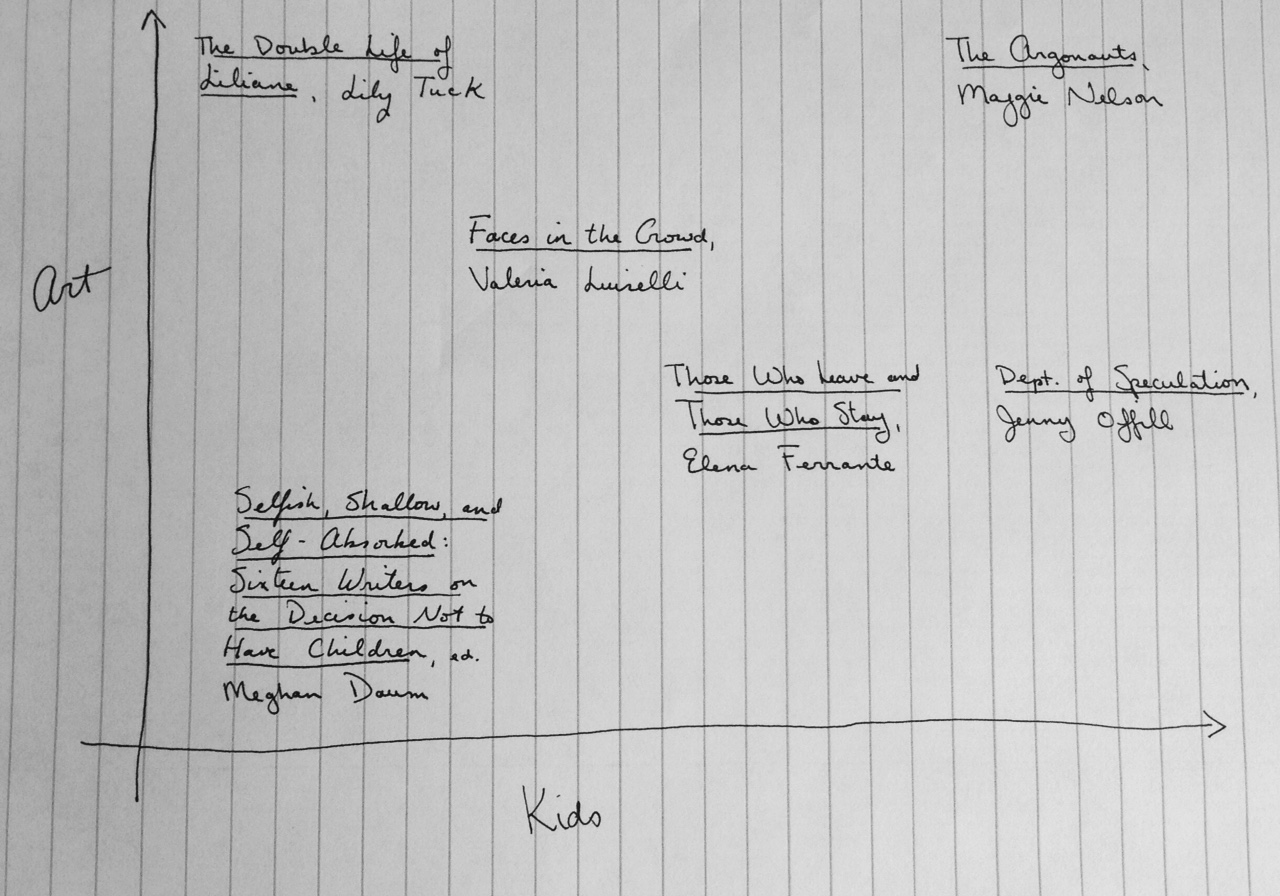

That question—how do writers have kids?—has been at the heart of a whole cohort of books published in the past year or so. Two are not at all fiction; two are fiction that I believe is intended to seem like nonfiction; one is fiction intended to seem like fiction; and one, The Double Life of Liliane, is on this graph as a control. It seems to me that Lily Tuck has the same concerns in The Double Life of Liliane as Maggie Nelson does in The Argonauts: who am I, who is my family, how much overlap do those questions have, and what do they have to do with me as a writer? The difference is that Lily Tuck wrote a novel about her childhood and Maggie Nelson wrote what I will call a critical memoir about her adulthood.

I will be honest: I did not expect to like The Argonauts. I’m not much for criticism. I picked it up in a bookstore and the first paragraph (it’s written all in separate paragraphs, as are Dept. of Speculation and Faces in the Crowd) irritated me. But my friend Fiona sent me a copy and when people I love give me books I read them, and thank God. It is beautiful. And it is a success story. There’s a comment in The Argonauts that got a lot of play—“Literally, physically, I cannot hold my baby at the same time as I write”—but she can, in every way but the literal. The point of the book is that Maggie Nelson is a writer, a brilliant and critically successful one, and she has a not-so-traditional family, and it works, and she is happy.

But then we have Jenny Offill and Elena Ferrante and Valeria Luiselli warning us that it’s not so easy. All three of their books are novels, so this is already more complicated than reading about Maggie Nelson’s real-life stepson and baby, but Offill and Luiselli don’t name their first-person female narrators, and Ferrante gives hers the same first name she’s chosen as her pen name. None of this is accidental, obviously. All three are choosing to create overlap between the protagonist and the implied author. They’re trying to trick us into reading fiction as autobiography. And so it’s hard not to take it as both a promise and warning when Offill writes,

The days with the baby felt long but there was nothing expansive about them. Caring for her required me to repeat a series of tasks that had the peculiar quality of seeming both urgent and tedious.

… But the smell of her hair. The way she clasped her hand around my fingers. This was like medicine. For once, I didn’t have to think. The animal was ascendant.

This from a character who introduced herself saying, “For years, I kept a Post-it note above my desk. WORK NOT LOVE! was what it said.” And: “My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead.” I have waved that line in my best friend’s face many times. Why do I want kids? I ask. Why do I have friends? Why do I ever go outside? I should be an art monster!

But once she has a child, the would-be art monster stops writing, except ghost-writing a book for a man she calls the almost astronaut, and her marriage acquires first bedbugs, then another woman. The translator protagonist of Luiselli’s Faces in the Crowd becomes terrified that her husband is leaving her, and terrified generally. Her bug problem is cockroaches, not bedbugs, and at the end of the novel she’s under the kitchen table with her children, “afraid of the darkness because the cockroaches might come out for a walk and we won’t see them. I’m woken by the sound of their little feet, scratching on the cement or the metal of the fridge. I cover the children’s ears so the cockroaches…can’t get into their dreams.” And there are no bugs in Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, but Elena can’t write once her daughter Dede is born.

It’s not rare for fiction to be unhappier than nonfiction, though I will say that The Argonauts is a strikingly happy book, and that it is perhaps part of Nelson’s project to prove that her family is a strikingly happy one. But it is true that of all these books, only Faces in the Crowd ends unhappily. Elena does resume writing. The protagonist of Dept. of Speculation leaves New York with her family, and in her new life she “has a little room now, one that looks out over the garden. She makes a note to herself about the book she is writing. Too many crying scenes.” If there is a conclusion to be drawn it is: You can do it. Just don’t expect it to be easy.

But of course, that’s the conclusion I want to draw. If you’re looking for a different one, you might read these books differently. And if you don’t know what you’re looking for, if you’re trying to make a decision, when you’re finished reading all of these, read Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on The Decision Not to Have Children. The essays in it, by writers ranging from editor Meghan Daum to Tim Kreibel to my serious writer-crush Michelle Huneven, will not tell you what to do. They’ll just make you think about yourself for a while, about what you believe you’re able to do and what you want to do. It’s the book equivalent of the exceptional mother with the screaming toddler who I sat behind on the 54 bus, but I promise that it won’t make your head hurt afterward.