How to Write Indian Literature

If you’re studying a nation’s literature, it’s best to know that nation’s language. English literature finds definition in its mother tongue, despite the linguistic leap from Shakespeare to Zadie Smith. American literature, whose myriad dialects are called upon by Walt Whitman, John Ashbery, and Nikki Giovanni, rests comfortably in its native discourse. Langston Hughes states complex emotions–“America never was America to me”–while writing poems understood across the United States.

If you’re studying a nation’s literature, it’s best to know that nation’s language. English literature finds definition in its mother tongue, despite the linguistic leap from Shakespeare to Zadie Smith. American literature, whose myriad dialects are called upon by Walt Whitman, John Ashbery, and Nikki Giovanni, rests comfortably in its native discourse. Langston Hughes states complex emotions–“America never was America to me”–while writing poems understood across the United States.

The Indian literary language is no one’s language–because it doesn’t exist, because there is no one Indian language. How, then, can anyone write Indian literature?

Studying the history of Indian literature shows us how the study of English literature developed into a discipline, as the very study of literature was created in India via British imperialism. But, in typical Orientalist fashion, it tells us little about Indian literature itself. This development does show, however, that the creation of “Indian literature,” was, at its root, deeply political.

India once recognized Hindi as the national language and vestiges of this policy persist. Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently expressed a request for government documents and social media to use Hindi, although a large number of Indian citizens don’t speak the language. One of the main languages of south India is Tamil; Kolkata primarily hosts Bengali speakers. Modi’s political premise simplifies reality; literature develops a space not to represent reality “as it is,” but to examine the many realities one can experience.

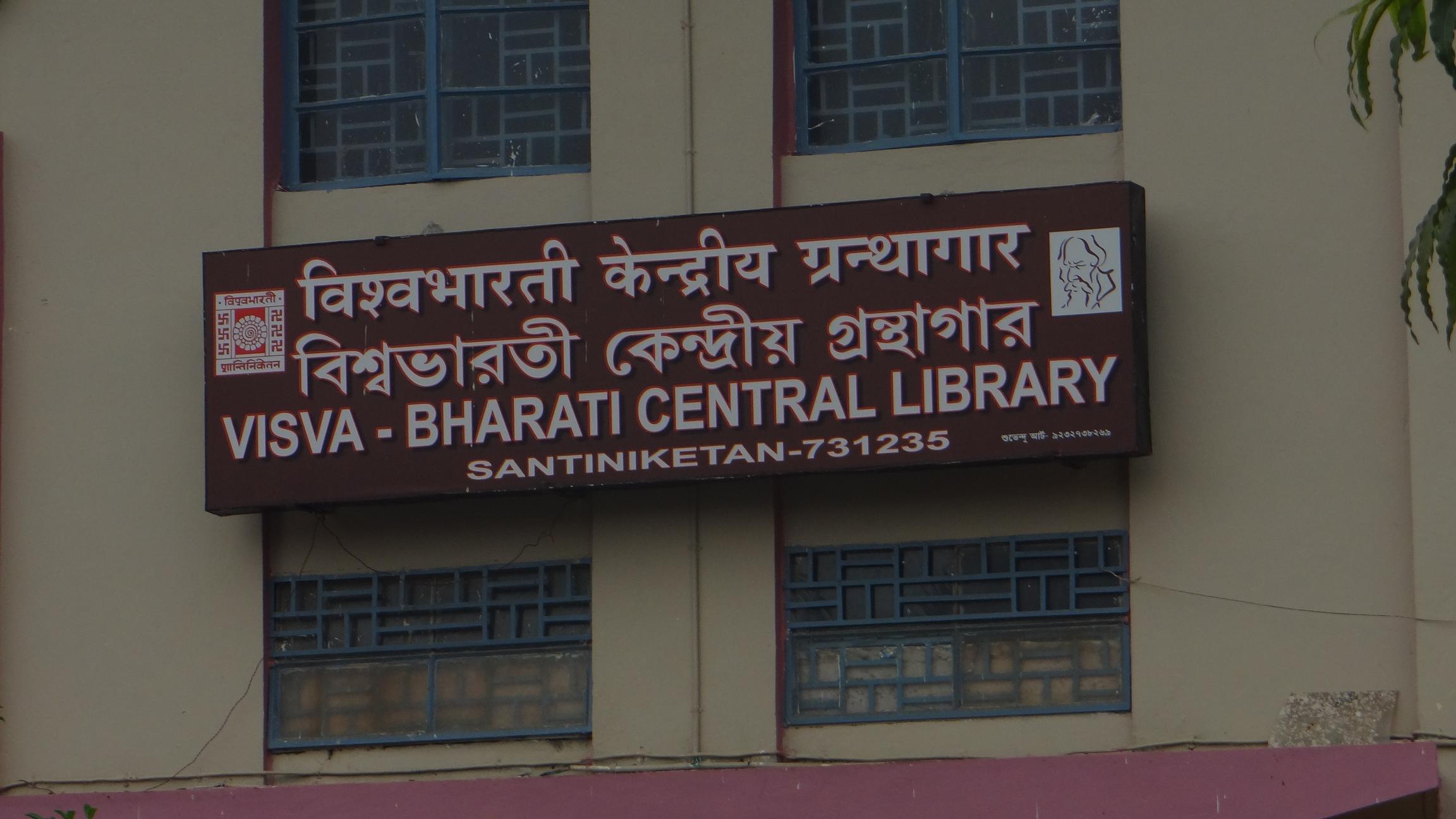

Some Indian literature, of course, is written in Hindi. But to say that Hindi could ever be the main language of Indian literature rings false. Rabindranath Tagore, India’s most famous poet, wrote in Bengali and, with the assistance of W.B. Yeats, translated his own work into English almost a year before receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature. Many contemporary Indian writers have work translated into English or compose in English.

This literary linguistic wrestling is not unfamiliar to other countries–Joyce, for example, faced the problem of contributing to Irish literature while writing in English. Prominent Indian writers working in the mid-twentieth century, including Kamala Das and Eunice de Souza, also wrote in English. There are two possible explanations for writers choosing English. The first involves an Indian writer claiming the historical oppressor’s language as his or her own language to subvert power roles. The second explanation for choosing English reflects the writer’s desire to reach a wider, international audience. Tagore might have never received the Nobel Prize if he didn’t undergo the work of translating his Gitanjali. This past year, the Indian-born Vijay Seshadri’s 3 Sections won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. 3 Sections features English-language poems.

But to claim that English might be the language of Indian literature is also untrue. While Oxford University Press publishes Indian literary anthologies and Indian novelists like Chetan Bhagat pen popular English paperbacks, the diversity of literature written using Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati, and other Indian languages cannot be understated. One of my favorite recent books of Indian poetry comes from N.D. Rajkumar, a fiery Dalit poet whose work was translated from Tamil by Anushiya Ramaswamy. His Give Us This Day a Feast of Flesh blows most Indian writing in English out of the water.

Another radical work comes from Meena Kandasamy, whose Ms. Militancy challenges caste and Hindu mythology using a feminist lens while resisting academic theory. The poems are composed in English. Comparing N.D. Rajkumar and Kandasamy shows one advantage of English writing: although both live in the state of Tamil Nadu, Kandasamy was a guest lecturer at the University of Iowa International Writing Program and Rajkumar works as a “daily wage labourer in the Railway Mail Service in Nagercoil.”

The linguistic complexity of India, in a sense, helps an American reader resist Orientalist views of India and ideally read against tokenism. Anyone who simplifies a nation’s discourse misreads that nation. When you’re reading the texts of a recently created nation like India, which was only founded in 1947, you must know the political, historical, and linguistic backdrop, or you will miswrite what you read.