If Poets Wrote the News

“It is difficult to get the news from poems yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.” –William Carlos Williams

The New York Times published an interview this month with poet Daniel Nadler entitled “Why Poets Can Make Better Search Engines.” When I read the headline, I immediately thought: it must be because of their attentiveness to language. Nadler suggests, “Poetry teaches you how to build a better search engine because it teaches you how to reflect on the needed balance between expectation, utility and serendipity.” Which is to say, poets teach us how language relates to itself, how language relates to us, and how words relate to ideas and one another.

After I read Nadler’s interview, poet Jenifer Park asked me what the world would look like if poets wrote the news. I took a moment and thought about the news as it is now: fast paced, available 24 hours, updated constantly, “objective,” often reckless. For instance, during the Dallas police shootings this summer, the Dallas Police Department wrongly named a suspect on Twitter, leading to death threats against the mistaken suspect.

It’s the recklessness and misunderstanding of objectivity that concerns me most where the news is involved, and I think those two problems are related. If we can begin to acknowledge that the people reporting and writing the news are individual subjects, individual human beings who are capable of mistakes and who retain always the bias of their respective identities, than perhaps we can next acknowledge that these people are inherently subjective. So then what would poets do that reporters don’t?

A good poet acknowledges context. Acknowledges that different people speak for different groups. Take Amiri Baraka’s poem “Somebody Blew Up America.” His use of vague language in the title and opening line—“They say it’s some terrorist”—mimics how news often travels through the world, trading in vagaries and evasive blame: “Somebody,” “They.” Baraka acknowledges this in the first few lines of his third stanza when he says, “They say (who say?)/Who do the saying/Who is them paying.” Baraka interrogates the Us vs Them dichotomy that arises out of violent events as reported by the news, then spread word of mouth by news readers, and he reveals how the burden of blame often falls on marginalized groups and people. Or like Danez Smith says in their poem “Principles”:

Two poems responding to violent murders of marginalized bodies this summer effectively captured not just the events themselves, but the nuances of context surrounding those events. This is where the news often fails. It is reported by people with some distance from the subjects of the news story. But when Christopher Soto and Danez Smith responded to the Orlando Shootings and the police murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, they put their own bodies in the context of the events, because when bodies that are like yours are being killed, you, too, are part of the news, but a part that usually gets left out.

Soto’s poem “All The Dead Boys Look Like Me” acknowledges how reading the news shapes experience:

Smith’s & Soto’s poems also built a larger context for reminding us why these violent events occur to begin with. They remind us of the larger structural racism and queer/transphobia present in the world where this violence is unending.

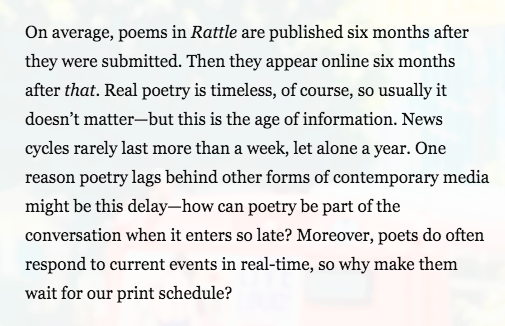

The journal Rattle considered the question of poetry and the news from an angle more related to the speed of the publishing process than to the relationship between news and poem/poet, but the result reads a lot like portions of a newspaper run by poets might. Rattle explains:

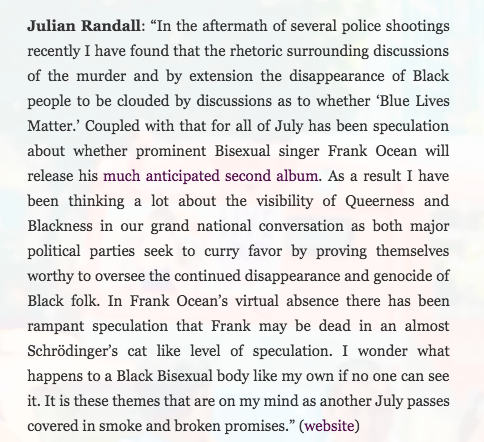

The poems they’ve published for this project thus far are varied in subject but all have one thing in common: an attentiveness to language and context that allows for a fuller understanding of the interconnectedness of news events, the identities and bodies that report on them, and the identities and bodies that are subjects in them. Julian Randall says of his recent poem for Rattle:

Randall’s poem’s second stanza connects multiple news stories the way social media—one of our main contemporary sources of news—does, and in so doing, he demonstrates the way context, serendipitous or not, frames the news.

Poets responding to the news is not new, and the examples are endless. Frank O’Hara responding to the death of Billie Holiday. Martín Espada responding to the death of workers at the Windows on the World restaurant during the attack on the World Trade Center. But a world of news written by poets would be a world of news that’s embodied and situated. News that’s careful, measured, and honest about the role bias will always play in our lives since language is never neutral.