Modern Day Ghost Stories

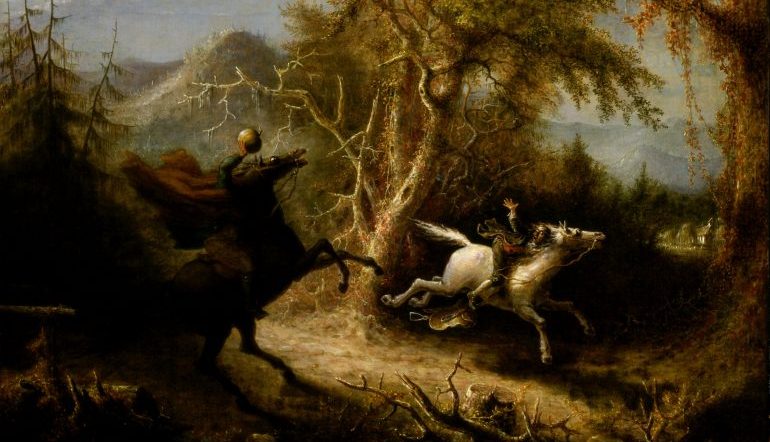

Ghost stories, traditionally the domain of campfires and horror films, have endured since our earliest recorded histories. Without the ghost of Hamlet’s father appearing in the first scene of Shakespeare’s play, for example, none of the ensuing tragedies of one of the English language’s greatest works of drama would have taken place. When Ebenezer Scrooge is confronted by the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come at the end of A Christmas Carol, he finally feels his heart soften and changes his life’s course. In American literature, the Headless Horseman of Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and the beating heart of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” torment the protagonists, although their supernatural powers are up to a reader’s interpretation. In ghost stories from antiquity to modern day, what endures is the ghost—some specter of a former life—and the haunted, those left living who fear what they cannot fully see.

Ghost stories, traditionally the domain of campfires and horror films, have endured since our earliest recorded histories. Without the ghost of Hamlet’s father appearing in the first scene of Shakespeare’s play, for example, none of the ensuing tragedies of one of the English language’s greatest works of drama would have taken place. When Ebenezer Scrooge is confronted by the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come at the end of A Christmas Carol, he finally feels his heart soften and changes his life’s course. In American literature, the Headless Horseman of Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and the beating heart of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” torment the protagonists, although their supernatural powers are up to a reader’s interpretation. In ghost stories from antiquity to modern day, what endures is the ghost—some specter of a former life—and the haunted, those left living who fear what they cannot fully see.

In the December issue of The Bookman from 1929, ghost story expert M. R. James lays out five rules for supernatural tales, one of which is the setting, which must be the writer’s own day. “The seer of ghosts must talk something like me,” he writes, “and be dressed, if not in my fashion, yet not too much like a man in a pageant, if he is to enlist my sympathy.” Looking for ghosts in contemporary literature means looking for ghosts that look nothing like the ones Shakespeare and Dickens dreamed up. The most chilling hauntings are the ones we can relate to—the ones happening in our real lives, or the lives of people we recognize, whose fear looks like our fear, and whose triumph is our triumph.

In contemporary memoir, the ghosts that haunt the narrators are past selves, dead loved ones, or other traumas that manifest in these writers’ lives. In Kiese Laymon’s Heavy, for example, Laymon explores his survival of the generational trauma of growing up poor and black in Mississippi, as well as addictions to food and gambling. Jesmyn Ward’s The Men We Reaped, another recent memoir, is framed around the deaths of five men Ward knew—all family and close friends—within a four-year period, who she refers to explicitly as ghosts: “Men’s bodies litter my family history,” Ward writes in her first chapter. “The pain of the women they left behind pulls them from the beyond, makes them appear as ghosts. In death, they transcend the circumstances of this place that I love and hate all at once and become supernatural.” For both these writers, their inherited and lived traumas follow them like phantoms throughout their lives.

“I wanted to write a lie,” Laymon says in the opening lines of Heavy, which he addresses to his mother. “I did not want to write honestly about black lies, black thighs, black loves, black laughs, black foods, black addictions…black consent, black parents, or black children. I did not want to write about us.” Instead, Laymon writes about all these truths, truths so painful and tangled that on the book’s third to last page, Laymon knows their wounds will never scab over completely. “There will always be scars on, and in, my body from where you harmed me. You will always have scars on, and in, your body from where we harmed you. You and I have nothing and everything to be ashamed of, but I am no longer ashamed of this heavy black body you helped me create.” Instead, his black body, a physical manifestation of what has haunted him—its weight, the way it is perceived by white teachers and classmates and students and police—becomes a living memorial to the trauma he has overcome. It becomes a source of life that continues long after the book has ended. Laymon releases his ghosts, or is released by them, but perhaps no story of blackness in America can end with complete release. Like Scrooge’s three ghosts of Christmas, Heavy ends with reconciliation of self and past, self and present, and hopes and dreams for the future self.

In Men We Reaped, Ward grapples more directly with the ghosts of the black bodies she has loved. Ghosts, Ward’s brother told her when they were younger, existed when someone died. “From 2000 to 2004, five Black young men I grew up with died, all violently, in seemingly unrelated deaths,” Ward writes in her memoir’s prologue. The recounting of these tragic deaths provides the structure for Men We Reaped. The young men themselves were haunted—by poverty, lack of opportunity, fear, and isolation. Some turned to drugs, died in accidents, or died by suicide.

Ward works with two storylines, one moving chronologically through her childhood—as she explains it, “my family and how I grew up”—and the other in reserve chronological order, revisiting the deaths of each of the five Black men who died, culminating in the heart-rending chapter about the death of Ward’s brother. The ghosts of Ward’s and her community’s dead are granted, in the in-between chapters of childhood and young adulthood, life and dialogue for “a few paltry pages.” This narrative structure, in which our attention is drawn to the ghosts as children and teenagers to emphasize that their lives are ultimately cut short, amplifies the ghosts’ supernatural importance. By focusing on the perils awaiting the Black men Ward knew, she can also show the importance of the haunted—in this case, the Black women left behind to mourn, remember, and retell the stories of their ghosts.

In “Some Remarks on Ghost Stories,” James explains that fictitious ghost stories must be presented as though they are factual to be truly frightening. The goal of memoir is not explicitly to frighten but to present the experience of the author so that the reader might enter another life as they read. The hauntings within, quite real and often terrifying, portray a truth that moves us deeply.