Reading Carmen Maria Machado’s Update on Carmilla

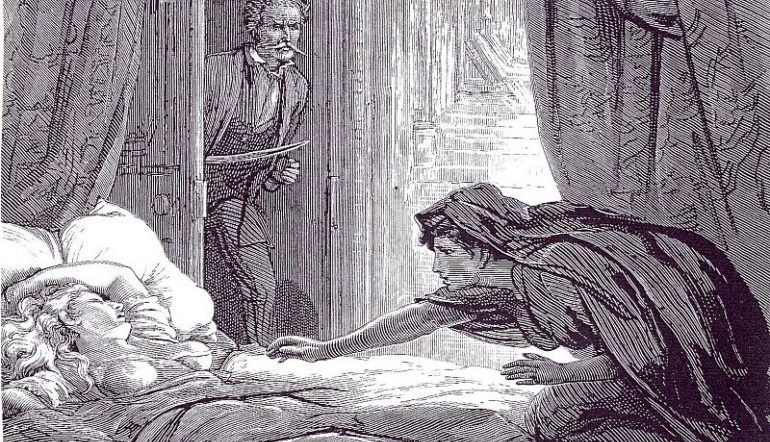

Twenty-five years before Bram Stoker published Dracula, a different Irish author was quietly draining maidens in the night. Like Dracula, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, published in a serial format between 1871 and 1872 in the journal The Dark Blue, is named for its vampire, an incredibly sexy monster of possession, desire, and blood. Both Dracula and Carmilla turn their attentions to young women and establish certain rules of the vampire canon: old money, puncture wounds, wasting away, conversion, animal transformation, sleepwalking, the necessity of sleeping in a tomb, decapitation. But Carmilla is a much simpler tale, revolving around just one obsessive and sensual relationship: the one between Carmilla and the narrator, Laura. In April, Lanternfish Press released a new edition of Carmilla, edited by Carmen Maria Machado, author of the much lauded 2017 collection, Her Body and Other Parties. Machado’s introduction and edits are innovatively active rather than passive. Instead of merely presenting the story, Machado complicates Le Fanu’s original frame narrative, deepening the book’s meditations on who we listen to and who we believe in situations of horror.

Twenty-five years before Bram Stoker published Dracula, a different Irish author was quietly draining maidens in the night. Like Dracula, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, published in a serial format between 1871 and 1872 in the journal The Dark Blue, is named for its vampire, an incredibly sexy monster of possession, desire, and blood. Both Dracula and Carmilla turn their attentions to young women and establish certain rules of the vampire canon: old money, puncture wounds, wasting away, conversion, animal transformation, sleepwalking, the necessity of sleeping in a tomb, decapitation. But Carmilla is a much simpler tale, revolving around just one obsessive and sensual relationship: the one between Carmilla and the narrator, Laura. In April, Lanternfish Press released a new edition of Carmilla, edited by Carmen Maria Machado, author of the much lauded 2017 collection, Her Body and Other Parties. Machado’s introduction and edits are innovatively active rather than passive. Instead of merely presenting the story, Machado complicates Le Fanu’s original frame narrative, deepening the book’s meditations on who we listen to and who we believe in situations of horror.

Framing devices are extremely old-school. Within the gothic horror genre, the “found narrative” frame is common to the point of cliché. Working within a speculative genre like horror is difficult—a writer needs to dispense with some expectations of reality but also make things close enough to the plausible that the reader feels haunted, even personally threatened, by the events of the story. The found narrative frame (letters found in an attic, a series of newspaper clippings in a lost scrapbook, etc.) is useful in this effort because it appeals to authenticity. Think of all the gruesome urban legends that begin not with, “Once upon a time…”, but with “A few years ago, my cousin’s friend…”. In Carmilla, Le Fanu goes a step beyond this, using a found narrative that appeals not just to authenticity but to patriarchal authority: the story comes from the letters of a male medical doctor.

The original prologue to the novella is brief, not even a page long. In it, Le Fanu claims that he found his story among the papers of Dr. Hesselius—Le Fanu’s invented chronicler and connoisseur of the paranormal—who had carried on a correspondence with Laura. Le Fanu tells us two things: first, that he’s removed most of the more involved (read: boring) notes from the doctor on the medical specifics of the disease of vampirism; second, that he wanted to conduct a personal interview with Laura but couldn’t because she had since died. He doesn’t tell us how she died (in the end, she survives her involvement with Carmilla). The novella picks up from there, in Laura’s own voice, which continues, uninterrupted, through to the conclusion.

Enter Machado. In her introduction to the new edition, Machado begins with a straight face and an appeal to her own authority by quickly noting the publication history expected in an introduction, along with comments on Le Fanu’s use of the fictional Dr. Hesselius. From there, she continues, in the same academic tone, to discuss a new history of the book that has been unearthed. Le Fanu’s invented correspondence was stolen from a real one, she says, between a young woman named Veronika Hausle and a real doctor, Peter Fontenot. In the correspondence, Veronika tells the doctor of her love for a woman named Marcia Maren in a narrative full of “nascent desires familiar to any sexual creature.” Machado shifts our interpretation of the fictional Laura before we even meet her, saying that in her true form as Veronika, she wrote “specifically of her own desire, not the mix of attraction and repulsion that LeFanu repeats over and over.” Machado is far too cool to break kayfabe and insists upon the authenticity of this history, even in a hilarious and reality-bending interview with Electric Literature. But the history is, of course, just as invented as Dr. Hesselius. Machado, unwinking, does leave clues to the game she’s playing. She uses an anagram of her own name, for instance, Marcia Maren, just as Carmilla uses an anagram to disguise her true identity.

In this updated presentation of the story, Machado is both playfully reclaiming a story that was never stolen while also reclaiming a history that definitely was: the literary history of queer desire. Machado’s introduction also serves to re-ascribe a bit of the agency lost to Laura. Le Fanu made the lesbian Carmilla a monster, and he also had Laura suffering from the effects of vampirism without being allowed to discuss her own disease. The most terrifying bit of the whole novella, with the exception of a few bloody figures and crawling bodies deployed in age-worn but effective jump scares, is the dread that comes from the fact of Laura’s lack of medical agency. All her doctors are men, and they tell her nothing. Her own father asks her to go away when she has been examined, so that he can discuss the results without her present. In her introduction, Machado makes Veronika “the daughter of an English soldier and a minor Hungarian noblewoman, best known not for her tangle with ‘Carmilla’ but her advocacy for women’s agency in the realms of faith and medicine.”

Beyond her opening re-frame, Machado has also edited the work itself. Some of those edits are intended to reflect a “modern grammatical sensibility” and to “interrupt LeFanu’s passionate and unrequited love affair with unnecessary commas,” but others are included to be “illustrative.” There are moments when Machado will introduce an entirely new character or bit of invented folklore in a footnote. She also makes Le Fanu’s Victorian reticence around sex a little more explicit, such as in the footnote, “If this isn’t an orgasm, nothing is.” She says of her mission, at the end of her introduction, that “the act of interacting with text—that is to say, of reading—is that of inserting one’s self into what is static and unchanging so that it might pump with fresh blood.”

One of the best narrative turns of Carmilla takes place when a travelling picture restorer cleans an old oil painting to reveal that its subject bears a striking resemblance to Laura’s mysterious houseguest, Carmilla. In this new edition, Machado has taken on the duty of an antique frame restorer. She could have simply polished the gilt wood and rehung it, but ultimately she decided to give the portrait a double frame and to add brushstrokes, few and small but consequential. The resulting work is a hybrid form, a beautiful and terrible monster that shifts whenever you look at it, back and forth between history and fantasy, repression and liberation, horror and desire.