The Ripples of History in Howl

In 1980 I was attending grammar school and living behind the Iron Curtain. I strolled the streets of Budapest together with many youngsters, watched and pestered by the police for the sheer fact of our existence. One day, I got into a group that was heading towards Eötvös Loránd University. I vaguely remember that it was morning and I am not sure what gave me the right to be in the street. Perhaps it was summer, or I might have been ditching school for the day, to do something else, something much more important. A student who was the friend of a friend stole us into the building, straight up the stairs to a small lecture hall. The door could only be opened to a slit and we squeezed into the room, which was packed like a tin of sardines. I stood with a hundred others, pressed body to body. The impatience in the hall was palpable.

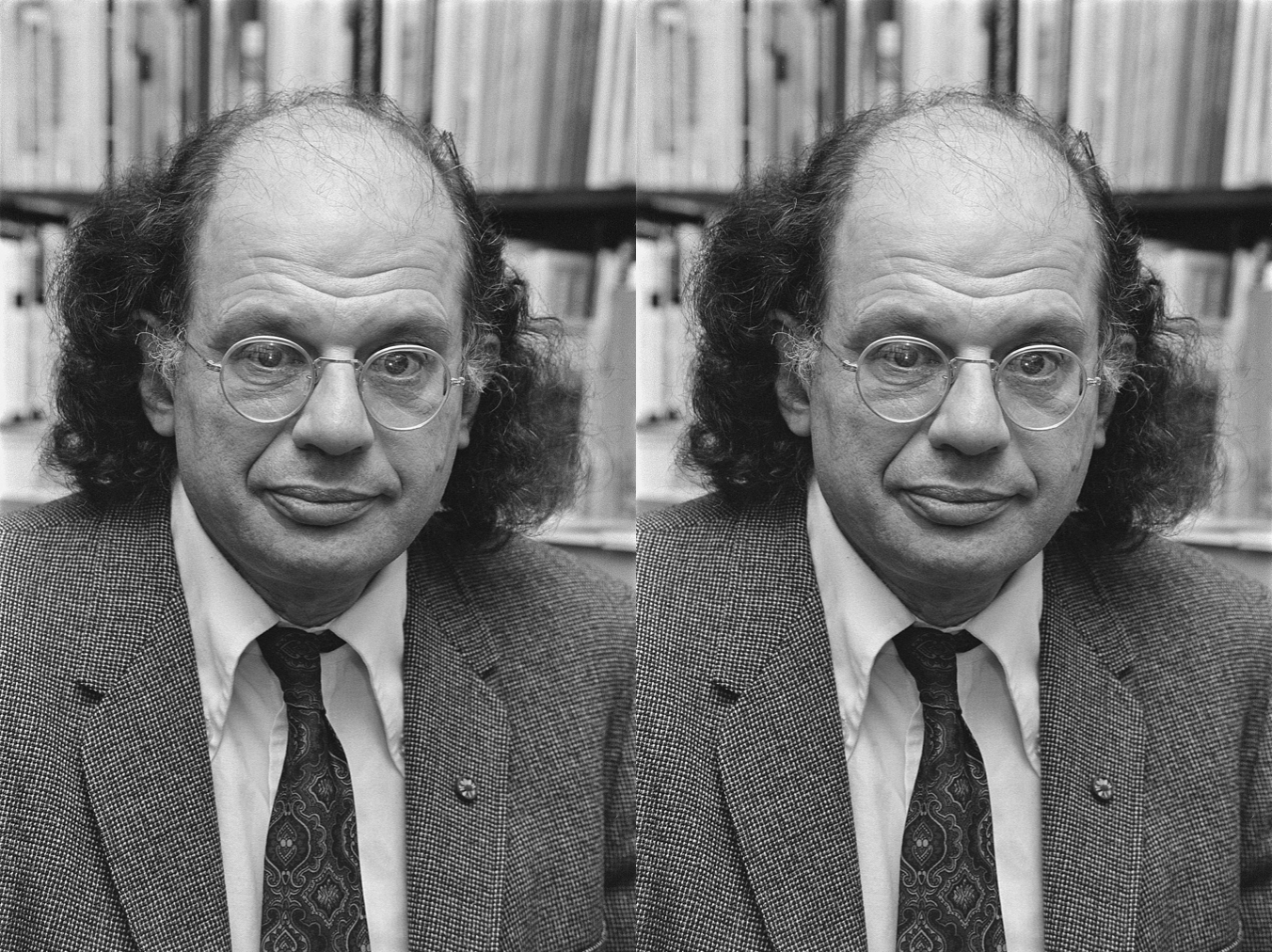

After a few moments, the door on the right behind the lectern opened and in came Allen Ginsberg, bald and black-bearded and wearing black rimmed glasses, followed by his constant companion Peter Orlovsky, who had long grey hair that he’d put up in a ponytail that hung down to his bottom; a young boy carrying a guitar; and Ginsberg’s Hungarian translator, István Eörsi, a lecturer at the university. Ginsberg unpacked his harmonium slowly and sat down in lotus position on top of the long desk at the front of the room. He started: “Tiger, tiger burning bright, in the forests of the night,” and the crowd chanted with him. I knew nothing about Ginsberg’s “Blake vision,” an auditory hallucination he had in 1948 when he heard William Blake reciting his poetry, but Ginsberg’s voice was mesmerizing, shamanic, and ultimately transformative. I was in bliss for the next hour.

Ginsberg’s prose-poems are heavily reliant not only on imagery but on repetition and an internal rhythm, which gives them a mantra-like power, mirroring his Buddhist faith. Many people indeed thought that Allen Ginsberg was a prophet—not of the Buddhist faith, but of freedom of speech.

***

Howl, Allen Ginsberg’s first volume of poetry was published in 1956 in San Francisco. This was the year when the Hungarian Revolution took place and was broken down by the Soviet Union. While people in Hungary were struggling to escape Stalinist terror, on the other side of the world Ginsberg was “howling” for personal freedom. Consequently, the manager of the bookstore that sold Howl was jailed and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the publisher of Howl via City Lights Books, was subjected to an obscenity trial in 1957.

Ferlinghetti was acquitted based on the First Amendment. In Hungary, in 1980, we still had no freedom of speech. Human rights were wholly disregarded. We admired the Beat poets, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, and Corso among them, for their freedom and willingness to criticize the American government.

Ginsberg had long admired Socialism, as his parents had been supporters of the Communist Party in the US. He told the story in his poem “America”:

America when I was seven momma took me to Communist Cell meetings they sold us garbanzos a handful per ticket a ticket costs a nickel and the speeches were free everybody was angelic and sentimental about the workers it was all so sincere you have no idea what a good thing the party was in 1835 Scott Nearing was a grand old man a real mensch Mother Bloor the Silk-strikers’ Ewig-Weibliche made me cry I once saw the Yiddish orator Israel Amter plain. Everybody must have been a spy.

Perhaps this curiosity is what brought Ginsberg to Eastern Europe, but he had to have been disappointed. “Peter & I are back from couple months…Hungary-Austria-Switzerland-Germany—made little money but saw a lot—Red Lands not good, Hungary pretty dreary bureaucracy—I guess communism just doesn’t work,” wrote Ginsberg to a friend on a postcard.

When he visited, he brought his “life long sex-soul union,” Orlovsky. For us Hungarian youngsters, it was unfathomable that a gay couple could be open about their relationship. In truth, Ginsberg was open about his sexuality long before the gay liberation movement—at the time of the first publication of Howl, Ginsberg’s confessional poetic style was scandalous because he was queer and wrote about it, and because he sympathized with the Communist movement, and so his publisher was taken to court for “obscenity.”

***

I left Hungary in 1981, and never questioned that freedom of speech has always been a feature of the West. I have only recently learned of the blasphemy clause in the Irish Constitution that forbade anyone to say anything bad about God—a clause that was recently removed, granting Ireland’s citizens full legal access to free speech in 2018. Hungarians have the worst curses in their language on the planet, featuring God in sexual acts, so I grew up hearing people spitting blasphemes when they were angry. Nobody was taken to court for this, but God-fearing people avoided bad language; we all have a built-in censor made from our beliefs, upbringing, and self-imposed conventions. Howl, however, is the manifestation of the freedom of expression, suggesting that the writer should refuse inhibition and self-censorship, for all that is human should be celebrated.

Now I live in Ireland, where the Republic has seen three referendums in the past few years, which rapidly brought it up to the level of most European countries, regarding personal freedoms. The first one acknowledged same-sex marriage, the second repealed the abortion ban, and the third removed the blasphemy clause from the constitution. The opposite trend has been seen in Eastern Europe. Democratic Hungary had to endure an amendment of the constitution in 2011 that introduced “the protection of the unborn” and declared that while gay couples can register their relationship, marriage is only possible between a man and a woman. In 2013 Russia re-introduced blasphemy laws to stop the activity of Pussy Riot.

While freedom of speech is granted, then, in the western world, governments across the globe are still trying to enforce control, wherever they can. The internet has seen censoring, for example, mirroring the black-listing of books by Hungary in the twentieth century. Books like Animal Farm, 1984, Doctor Zhivago and even Gone with the Wind were deemed to be decadent or revolutionary—and we could not have more revolutions after the Russian Revolution of 1917, which was supposedly the best and most advanced in history. Hand-typed versions of these books were passed around in secret.

In the same way, Hitler’s Mein Kampf was banned from publication in Germany for forty years after the end of WWII. Since it is now in the public domain, you can find the text for free on many websites. Will reading the book feed “slothful ignorance”? The fear is justified. You only have to look at the conspiracy theories spreading like wildfire over the internet to see how inbred hate is in humans and how it can thrive on fear. When societies become polarized, dictators gain power.

Ginsberg, although he was completely apolitical, influenced the politics of the twentieth century with his poetry. A Polish friend, who gifted me my copy of Howl (which he had lifted from the US Consulate General in Krakow) after we met in a German refugee camp, attempted to tell my fortune in 1981: “All idealists become cynics with time.” This was not true for Ginsberg; neither is it true for me.