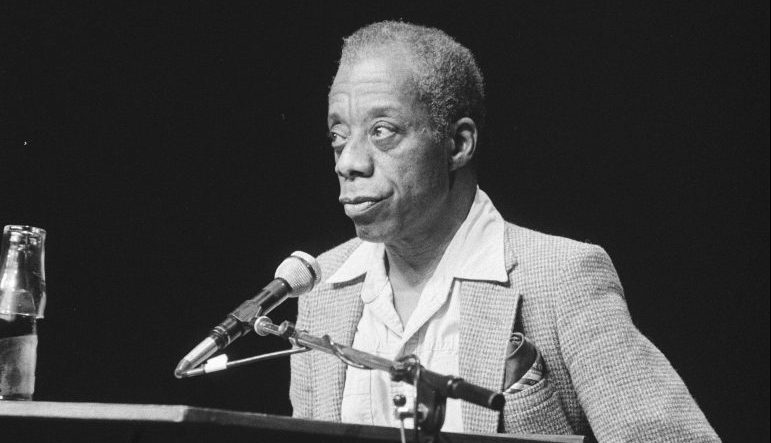

James Baldwin in the Archive

In 1948, the 24-year-old James Baldwin was working on a manuscript tentatively titled Ignorant Armies. The novel drew on the true story of Wayne Lonergan, a bisexual white man who had murdered his wealthy wife. It was a salacious case, landing at number nine on Raymond Chandler’s 1948 list of the “10 Greatest Crimes of the Century.” Simultaneously, Baldwin sought to explore the story of his friend Eugene Worth, a young African-American who died by suicide after jumping off the George Washington Bridge. Baldwin had unexpressed feelings for Worth and shortly after his death moved in with Worth’s girlfriend. They had loved the same person. Baldwin described the manuscript to his biographer David Leeming as a taboo murder tale in the vein of Richard Wright’s Native Son drawing on the Lonergan murder but with the desire to resolve or own his love for Worth tied in as well.

The manuscript for this novel has since been lost but was ultimately abandoned after years of writer’s block. What evolved from it, however, through a decades-long struggle with the legacy of Richard Wright, Henry James, and the white Lost Generation, as apparent from fragments of the work housed at the Cullen-Jackman Memorial Collection at the Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library are the novels Giovanni’s Room and Another Country as well as one of his most enduring insights into the struggle to end America’s innocence.

A 16-page fragment dated 1944 gives a sense of Ignorant Armies. At its center is a three-sided love triangle between a woman and two men, Pete and Julius, set in a small southern town. The scandal of the men’s relationship causes Pete to leave for Greenwich Village where he has a failed relationship with an older woman named Cass in an attempt to cleanse himself of his homosexual encounter. Unable to do so, he’s left to confront himself. The final line of the fragment reads, “Alone now, with no Cassandra, fallen between Cass and Julius, he dreaded, as he longed to meet, the dangerous time before him.”

Capturing that experience of the dangerous time, where all artifice falls away, represented a central artistic challenge for Baldwin. How could he express the love he was unable to express to Worth before he missed his opportunity to do so? The challenge is implied in the title of the lost manuscript, which comes from the final stanza of Matthew Arnold’s poem “Dover Beach”—“Ah, love, let us be true / To one another! for the world, which seems / To lie before us like a land of dreams / . . . Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light / . . . And we are here as on a darkling plain / Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, / Where ignorant armies clash by night.” The poem’s theme of “disillusioning” the love object, of getting to an unalloyed experience of love, is that same dangerous time both feared and desired by Pete in the fragment of Ignorant Armies.

In his essay “My Dungeon Shook,” Baldwin saw disillusionment, or loss of innocence, as a key step towards equality in America. Famously, he wrote, “It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.” In other words, white America lives in Arnold’s “land of dreams” while the rest of the world sees the “darkling plain” for what it is. Only a love where all illusions are removed could be powerful enough to resolve the legacy of hatred and inequality at the heart of the Lonergan murder, Worth’s suicide, and the country at large.

This may have been Baldwin’s instinct for the central theme of Ignorant Armies, yet by his own admission, he did not have the ability to draw it out of his manuscript. It was only by struggling with the works of other American authors over the course of years that Baldwin could reveal one of the most important literary insights in the twentieth century: that the opposite of innocence is not experience but freedom. Baldwin expresses this idea in an interview with Leeming on the topic of Henry James:

DL: […]if you had to pick two words that are basic to whatever we mean or Christopher Newman [a character in Henry James’ The American] would mean when we speak of the “American Dream,” wouldn’t they be freedom and, perhaps, innocence?

JB: Yes, but freedom and innocence are antithetical. You can’t have both.

DL: […] So, when you speak now of freedom…

JB: I mean the end of innocence. The end of innocence means you’ve finally entered the picture. And it means that you’ll accept the consequences too.

DL: By innocence, then, you mean the false objectivity that gives you the illusion that you can stand outside of something and describe it accurately without touching it, without paying your dues.

JB: Yes. And I also associate innocence with the role of the victim.

The genealogy of this insight, fully formulated here in 1986, has its origins in Baldwin’s attempts to solve the problem lying at the heart of the incomplete Ignorant Armies.

Baldwin was a writer who defined his literary project in opposition to other writers. His well-known and heavily discussed 1949 takedown of his mentor Richard Wright, “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” is both indicative of his need to transcend Wright and the social role of the “African-American Novelist,” as well as the debt he owes to Wright in his literary project. That he could admit to Leeming that Ignorant Armies explicitly took from Native Son, and perhaps failed because of it, shows how this opposition could also be the site of literary growth. Similarly, we can see in his work from 1948 to 1962 how he takes up themes of white modernist expatriate writers like Henry James and Ernest Hemingway while also directly challenging them.

In Atlantic University Center’s Robert W. Woodruff Library are a number of outlines and fragments that reprise Ignorant Armies and show its slow evolution into 1956’s Giovanni’s Room. There seem to be three works which share roughly the same plot: 1949’s So Long at the Fair, a later work entitled The Only Pretty Ring Time, and an even later work that was never realized past outline called Blackwater. So Long at the Fair and The Only Pretty Ring Time share with Ignorant Armies titles that reference verse between lovers (the nursery rhyme “O dear, what can the matter be?” and Shakespeare’s As You Like It, respectively). They also share baroquely evolved versions of the plot found in the 1944 fragment of Ignorant Armies. All three works are set in Greenwich Village and feature a character haunted by a homosexual relationship that occurred in a small town in the South. The burden of that relationship and the failure of each protagonist to own it inevitably lead to decline and suicide.

In So Long at the Fair, there is a panic murder that is reminiscent of Native Son, but elements that would come to define Giovanni’s Room also emerge. The male love interest in the 1944 fragment is Julius Colleano, an Italian-American, but in Blackwater, there are both Julius the Italian-American in the South and Giovanni the Italian in Paris. The Only Pretty Ring Time is written in narrative retrospect in the style of Giovanni’s Room. And the Blackwater outline includes Baldwin’s rationale for trying to tell the story in first-person despite “the terrible fluidity, as [Henry] James puts it, of self-revelation, the difficulty of sustaining the aesthetic distance between I and the author.” “The pain and tension arrive by way of his self-awareness and his helplessness,” he says, and “the denouement is made more bitter by his awareness of his defeat. At the same time, nevertheless, this defeat is a private, almost insupportable victory.” This notion of the private, almost unsupportable victory has echoes of the dangerous time of that first fragment, and anticipates the necessary instability and uncomfortable responsibility that Baldwin associates with “freedom.”

The early drafts of Giovanni’s Room held in the Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library archive, however, evince the difficulty of constructing a narrative that could manifest this idea. When Baldwin starts working under the title Giovanni’s Room, he has two scenes that he doesn’t stitch together: one with David and Giovanni in the bar, the other with them in the room. He treats each as a separate story. In a set of pages, helpfully typed on the reverse side of a 1955 letter from Howard University describing the staging of Baldwin’s play The Amen Corner, however, Baldwin synthesizes the two scenes. The book appears the next year, so it is safe to assume these are among the final drafts. In order to accomplish the marriage of the two scenes, Baldwin calls upon The Sun Also Rises rather explicitly. David gets a girlfriend, Hella, who is in Spain playing Britt Ashley. “Perhaps she has a Spanish lover and is afraid to tell you,” Giovanni says to David, “Perhaps she is with a torero.” The draft is full of such nods to Hemingway’s experience seeking expats, down to the coquets drinking Cinzano and laughing “when someone whom they imagine to be typically French, or, worse who bears the marks of long expatriation, enters.” But if they laugh at the grizzled expat, Baldwin is laughing alongside them, since, to echo a well-worn phrase, if he is rigging his narrative with Hemingway’s cords, his plan is to sail in the opposite direction.

In the New York Times Book Review in 1962, Baldwin explicitly confronts the idea that writers like Hemingway and Henry James were “sacrosanct” and “touchstones” used to reveal the “lamentable inadequacy of the younger literary artists,” himself included. In his essay “As Much Truth as One Can Bear,” he argues rather that they are the inadequate representatives of the American experience because they have all failed to deliver what his title promises. Instead, “One hears, it seems to me, in the work of all American novelists, even including the mighty Henry James, songs of the plains, the memory of a virgin continent, mysteriously despoiled, though all dreams were to have become possible here. This did not happen. And the panic, then, to which I have referred comes out of the fact that we are now confronting the awful question of whether or not all our dreams have failed.” At issue in this statement is the essential innocence of the American character, that the virgin continent was mysteriously despoiled rather than, as Jill Lepore recently formulated it: “Between 1500 and 1800, roughly two and a half million Europeans moved to the Americas; they carried 12 million Africans there by force; and as many as 50 million Native Americans died, chiefly of disease … Taking possession of the Americas gave Europeans a surplus of land; it ended famine and led to four centuries of economic growth.” That any kind of experience, even the “inexpressible pain” of “innocence being lost” “which lends such force to […] the marvelous fishing sequence in The Sun Also Rises,” does little to address what that innocence conceals. Individual experience can’t negate innocence when that innocence is coded with racism and sexism. Experience transcends rather than confronts, a move that Baldwin sees as leaving poisonous American innocence rather intact.

The conclusion of his essay is a call to arms against this: “Not everything that is faced can be changed: but nothing can be changed until it is faced. The principal fact that we must now face, and that a handful of writers are trying to dramatize is that the time has now come for us to turn our backs forever on the big two-hearted river.” But even as Baldwin calls for a new literature intent on facing America’s problematic innocence, his approach is not to go around the work of the previous generation of American authors. Instead, he goes through it.

This piece was originally published on August 29, 2019.