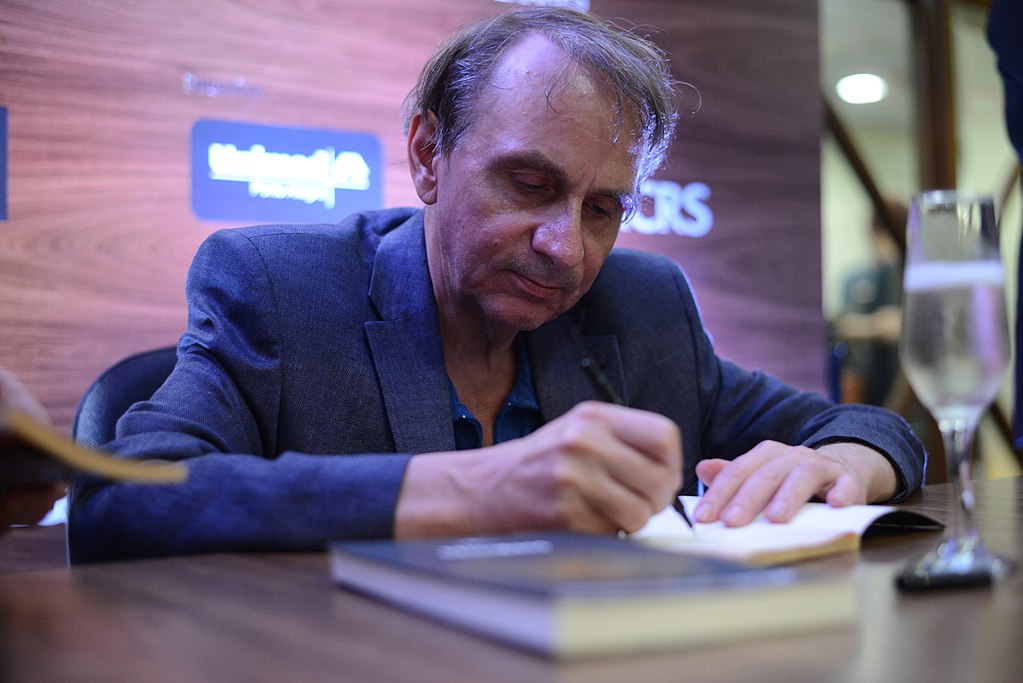

Michel Houellebecq’s Submission and the Liberal Man

Michel Houellebecq has always been a provocative writer and in fact considers himself to be a real provocateur, someone who “says things he doesn’t think, just to shock,” and who leans into that shock when he has a sense that people will hate it. With the release of his novel Submission, a story about a professor named François whose ennui leads him to eventually convert to Islam, Houellebecq perfectly stepped into controversy—the book’s release coincided with the Charlie Hebdo shooting in 2015.

At the time of the novel’s publication, Submission—which portrays a dystopian future in 2022 in which right-wing Marine Le Pen develops an alliance with the Islamic religious right in France—was considered to be Islamophobic. In 2002 Houellebecq had stated that Islam was a stupid religion (a statement he took back after actually reading the Qu’ran) so even before the release of Submission, his feelings were widely known.

Rereading the book now, in the wake of the 2016 election in which US voter turnout was just 58%, provides us with an interesting lens into the behavior of those who stayed home, or those on the left who voted for Trump.

In Submission, François thinks of himself as an ordinary French man of the intellectual left, one who is extremely judgmental of women and their shelf life, eats mostly non-French food washed down by copious amounts of French wine, and who believes that the weakening of the family as an institution is at the root of the country’s overall unhappiness. He misses a good chunk of a presidential debate while he’s heating his dinner–Indian food, by the way—and on election day he flees to the countryside, worried about the violence breaking out in Paris. He doesn’t stop to vote on his way out.

The new religious-right party, called the Muslim Fraternity and led by a character named Muhammed Ben Abbes, pushes out the socialist party. After forming an alliance with the remaining parties, including Le Pen’s National Front, they win. Change is not immediate, but it starts with the education system, where a Muslim education is made a viable option while funding to non-Muslim schools is severely reduced. Soon after, the state universities are shut down, including the one François teaches at—which in France is a problem since there are no private universities. They are reopened with only Muslims allowed employment. When François, this politically and religiously apathetic protagonist, pauses to consider what his future might look like, however, he does not think of the loss of his workplace—he instead, chauvinist that he is, mourns the loss of being able to imagine women’s privates under tight blue jeans, before quickly escaping into a fantasy of what Saudi women wear underneath their burqas.

When the Muslim Fraternity Party comes completely into power, it issues a subsidy to women with families—“meant to ‘restore the centrality, the dignity of the family as the building block of society,’” according to Ben Abbes—that immediately prompts many women to quit working, drastically reducing the unemployment levels that have been plaguing France. François decides to convert to Islam to return to work himself, lured by the promise of a tripled salary with academic accolades and admiration, and access to the ideal he didn’t know he had in mind when no strings attached sex with different women failed to fulfill him: up to three wives, at least one of them young and one of them able to cook—all forever subservient to and dependent on him.

Those who consider themselves liberal often want to deny that there are people who live and think as François, who sacrifice their ideals as well as the equality of others in favor of achieving personal success. But Houellebecq makes clear that the intellectual liberal man wants the same domination—in privately and in public—that every white nationalist wants. He wouldn’t care if maintaining this power meant that the entire world had to change, and he wouldn’t consider the consequences of those changes for others.

As Houellebecq said in his interview with The Paris Review, the insulting statements he makes in his books are not common in literature, though they are in private life—a fact that many are realizing in the wake of an election that brought to power a person many thought of as an obviously abominable and ignorant bigot. In Submission, then, Houellebecq holds a mirror up to society. What we see is ugly and offensive: those of us who think we stand for equality may not actually stand for that ideal at all; and if we do, we do not fight for it, instead allowing the currents to carry us wherever they go. Deep down, he suggests, all we really want is to submit to whatever will give us power. This is what discomforts us.

If we want to censor or ban books like Houellebecq’s, we do so at our own peril. That is not to say that such works should be read uncritically, but that we should read those books considered to be offensive with our eyes fully open, aware of the context in which they were created. The easy reaction is to cut those works of art and ideas off. It’s easy to dismiss the uncomfortable, and much harder to do the work of probing and acting on that discomfort.

Image: Michel Houellebecq (Fronteiras do Pensamento, 2016)