No Shoes, No Shirt, No Fiction: Let’s Get Out of the Restaurant

“I need to tell you something,” he said. He twirled his spaghetti around his fork.

She sipped her wine. “What is it?”

“Well.” He shoved the tangle of spaghetti in his mouth and chewed.

She fiddled with her spoon.

Suddenly, the waitress appeared. She had a grease stain on her apron. Her nametag read Renee. She symbolized harsh reality. “Can I get you somethin’ more, hon?”

He smiled and shook his head. He returned to his spaghetti. The waitress walked off, probably thinking about her ex-husband.

“What is it?” she asked him, tearing off a hunk of bread.

“I think,” he said, stirring his spaghetti in its blood-red sauce, “that we should stop perfunctorily setting fictional scenes in restaurants.”

Okay, a major caveat: Both of my novels have restaurant scenes. If you write, you’ve probably set scenes in diners, in coffee shops, in cafés, in bars, in fancy French bistros.

Okay, a major caveat: Both of my novels have restaurant scenes. If you write, you’ve probably set scenes in diners, in coffee shops, in cafés, in bars, in fancy French bistros.

Here’s why you do it, why I do it, why we all do it:

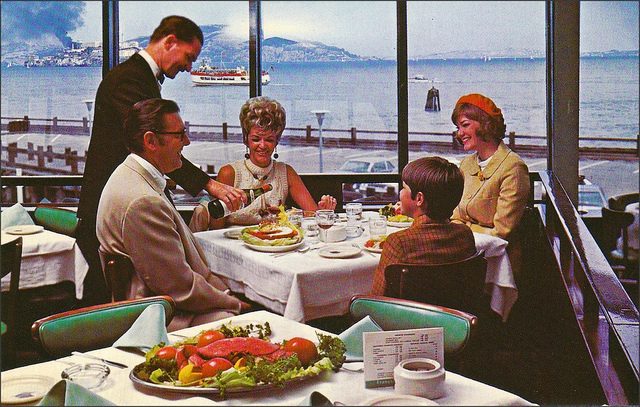

-The restaurant is a semi-private, semi-public space. People can have a conversation, but there’s always the threat of exposure, of embarrassment.

-Your characters have things to do with their hands. You can break up the dialogue with all that amazing spaghetti-cutting and soup-slurping and wine-swilling. And don’t forget the tearing of the big hunks of bread!

-Restaurants are familiar, and there’s a familiar trajectory to the evening. The scene doesn’t take much explanation. (He read his menu, which was a list of all the food items available for him to order. He needed to choose one appetizer, one entrée, and a dessert. He would be paying the restaurant in exchange for cooking his food and delivering it to his table.)

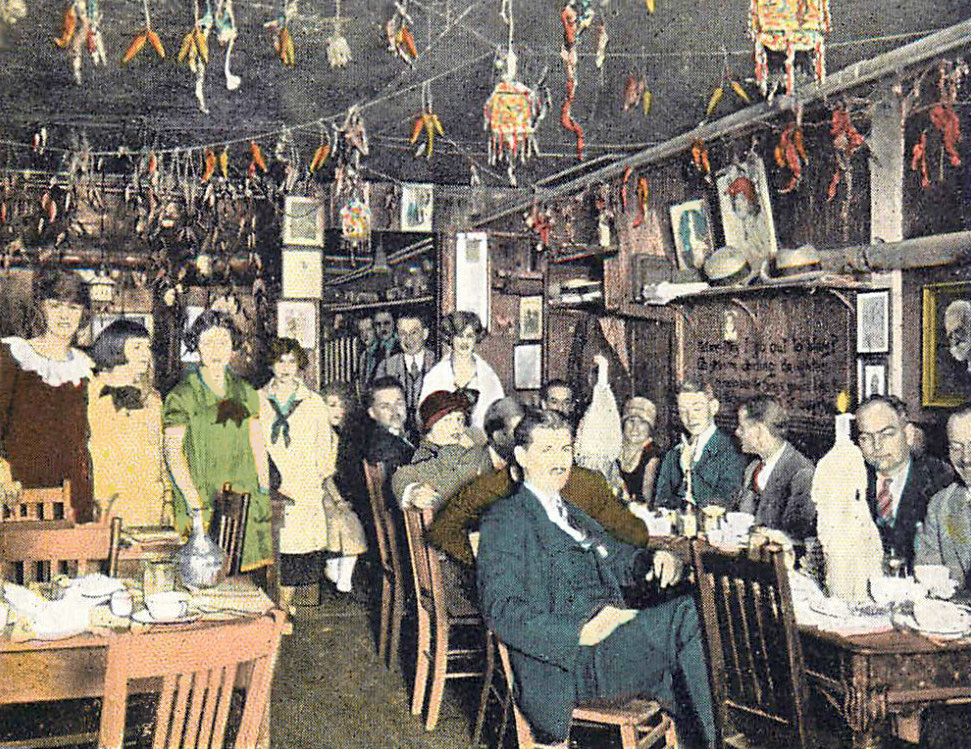

-It’s a set piece in fiction because it’s  a set piece in Hollywood. Restaurant scenes are cheap to shoot (and if you’re a producer, you can hire out the same diner that’s been used in fifty movies already this year; you don’t have to build a set). And since we get so used to watching the restaurant-scene trope (Where else do people ever break up, in a movie?) it’s a knee-jerk reaction to stick them in our fiction. He needs to break up with her . . . Wait, I’ve got it!

a set piece in Hollywood. Restaurant scenes are cheap to shoot (and if you’re a producer, you can hire out the same diner that’s been used in fifty movies already this year; you don’t have to build a set). And since we get so used to watching the restaurant-scene trope (Where else do people ever break up, in a movie?) it’s a knee-jerk reaction to stick them in our fiction. He needs to break up with her . . . Wait, I’ve got it!

-It’s a normal place for people to go, when they get out of the house. It’s realistic. It’s where dates happen.

-Sometimes there’s alcohol. And nothing advances a plot faster than lowered inhibitions.

-You get to describe food! Food is awesome! Especially when you’re stuck at your desk drinking cold coffee!

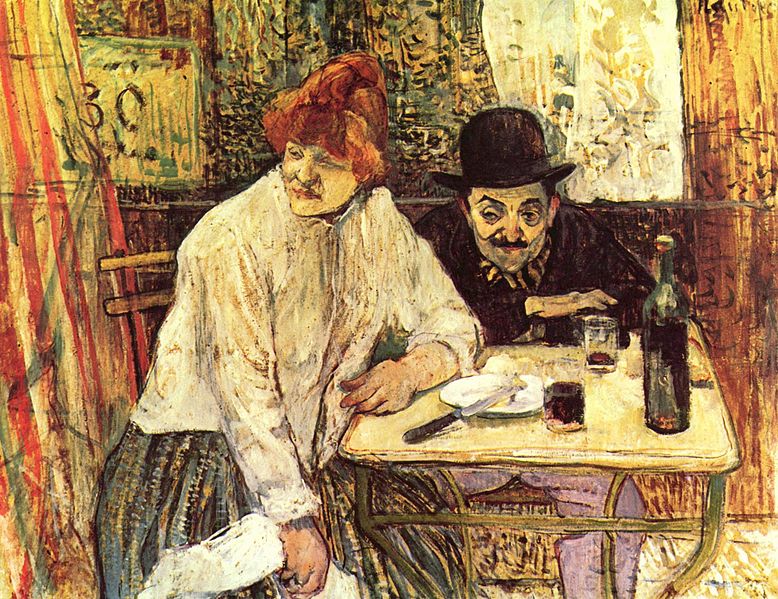

And there have been some brilliant scenes set in restaurants. Think of Hemingway’s café in “Hills Like White Elephants.” Or the diner scenes in Richard Russo’s Empire Falls. In Rishi Reddi’s “Justice Shiva Ram Murthy,” a vegetarian man is served meat at a restaurant, an incident that sets his life in a downward spiral. In stories like these, the space of the restaurant, the experience of food or drink, the seating arrangements, the encounters with servers and fellow diners, are not just background–they’re crucial. In John Cheever’s “Reunion,” the restaurants in Grand Central Station advance the plot (they’re how the father gets drunk) and heighten the son’s embarrassment. Look at Anne Tyler’s Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant, where the restaurant is the whole point.

And there have been some brilliant scenes set in restaurants. Think of Hemingway’s café in “Hills Like White Elephants.” Or the diner scenes in Richard Russo’s Empire Falls. In Rishi Reddi’s “Justice Shiva Ram Murthy,” a vegetarian man is served meat at a restaurant, an incident that sets his life in a downward spiral. In stories like these, the space of the restaurant, the experience of food or drink, the seating arrangements, the encounters with servers and fellow diners, are not just background–they’re crucial. In John Cheever’s “Reunion,” the restaurants in Grand Central Station advance the plot (they’re how the father gets drunk) and heighten the son’s embarrassment. Look at Anne Tyler’s Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant, where the restaurant is the whole point.

But (oh, the hypocrisy) here’s why you shouldn’t do it. Or why you should at least think long and hard before you do it. Or at least why I’ve started questioning it myself:

But (oh, the hypocrisy) here’s why you shouldn’t do it. Or why you should at least think long and hard before you do it. Or at least why I’ve started questioning it myself:

-That whole semi-private/semi-public thing is, in many cases, going to limit your characters. In absolute privacy, might they do or say something more interesting? More confrontational? And in true public (say, the veterinarian’s crowded waiting room with everyone listening), would there be more serious repercussions for their actions? This borderline space can be useful (think of Hermann Koch’s The Dinner, which couldn’t exist except in that public-private nexus), but more often it’s a cop-out, a way to protect characters from true conflict.

-All those great things your characters are doing with their hands, between lines of dialogue? All the unfolding of napkins and poking at the French fries? They’re boring as hell. And they have no impact on the action. They’re space-fillers, pure and simple. I do not care how many bites of quiche the character took, unless that quiche is poisoned.

-And that tense guy who “stabs his potato” or “saws at his filet” . . . I see what you’re doing there. Please don’t.

-Speaking of which: The  waitress? The one with the grease stain and the nametag? She’s been trapped in short fiction since 1942, serving that same horrible pot of coffee. Occasionally she gets to flirt. But she never gets to be a real character. I think it’s time we released her. Let her go serve happily at Waffle Hut and change into a clean dress already.

waitress? The one with the grease stain and the nametag? She’s been trapped in short fiction since 1942, serving that same horrible pot of coffee. Occasionally she gets to flirt. But she never gets to be a real character. I think it’s time we released her. Let her go serve happily at Waffle Hut and change into a clean dress already.

-Restaurants are familiar. Which is a con as much as a pro. We’re dealing with a blank slate, the opposite of setting. And setting can do such amazing things, can put such fantastic compression on characters and conflict. Our characters could be breaking up at the circus! In a canoe! In the supply closet at a Foot Locker during a tornado warning!

-The reasons restaurants work so well on film don’t all translate to the page. The movie breakup scene is always in the restaurant because when the woman screams and drops her fork, you can get the crowd reaction (the public side of that public-private space) in one second. On the page, not so much. Don’t believe me? Try writing the orgasm scene of When Harry Met Sally as fiction. (And then send it to me, please, because I need to see this.)

-There’s rarely something truly at stake in the restaurant. People will eat their food, they’ll converse – and we know exactly how this meal will end. With the paying of the bill. Of course there might be exceptions: there’s an engagement ring in the cake, there’s a gun behind the toilet, that waiter is really a Ukrainian spy. But for the most part, what’s immediately at stake is the chewing and swallowing of food.

Would I move Nick Carraway’s encounter with Meyer Wolfsheim and Gatsby away from that “well-fanned Forty-second Street cellar”? Not for a million bowls of the succulent hash that Wolfsheim eats with ferocious delicacy. But I’m going to continue to push myself and my students to consider whether that lovely new adultery scene really needs to happen at the café, at the Starbucks, at the corner bar on 25-cent wing night.

Occasionally, the answer is yes. But more often, it’s time to take your doggie bag and hit the road.