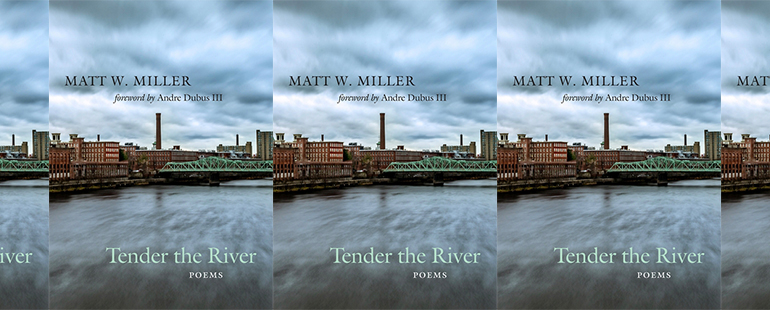

“Nothing lasts, nothing is solid, as much as we think it will be”: An Interview with Matt W. Miller

I have been following Matt W. Miller’s poetic trajectory with admiration since the publication of his second book, Club Icarus, in 2013, and have been publishing him at Green Mountains Review, where I serve as Editor, ever since. Known for his commanding narrative poems that deal with the ways in which ordinary life can become extraordinary, Miller frequently touches on family, community, history, place, and mythology. His fourth book, Tender the River, out last month, is no exception. Tender the River chronicles in documentary poetics the history of the Merrimack River, braiding together its many histories and voices from the perspective of the twenty-first century moment, in which the insistence of memory resides everywhere and in everything: people, the river, the land, industry, relationships—in short, in one’s spirit. While reading it, I couldn’t help but think of Langston Hughes’s seminal poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” in which Hughes interrogates four rivers of huge importance to his history and life narrative: the Euphrates, the Nile, the Congo, and the Mississippi. Hughes says, “I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.” Indeed, the Merrimack River of New Hampshire and Massachusetts runs in Miller’s veins as he explores how this river has shaped the many peoples it has encountered.

Tender the River documents the history and boundaries of place through the prism of the river, braiding all the strands of the Merrimack from its geological beginnings to the First Nations to the Industrial Revolution to the present—all the while engaging with issues on the forefront of our societal consciousness: racism, sexism, and environmental degradation. In the collection, the Merrimack serves as a microcosm of the macrocosmic story of our country’s creation stories and myths. Poems about the textile mills of Lowell, a city of immigrants on the banks of the Merrimack in Massachusetts, address the creation stories that established “work ethic” as a way of escape and redemption from poverty, from suffering. “Ghazal: Augumtoocooke” addresses the erasure of the Pennacook tribe: “Down by Macpherson Park, lithe Irish, Cambodian, Greek, and Dominican boys / sweat half-court hoops brilliant under the rim knowing shit about Augumtoocooke,” Miller writes, “though it might get a mention at McAuliffe Elementary studying Indians a whole week.” The collection even takes on one of our biggest creation myths of all: e pluribus unum, out of many one. As he challenges our history, Miller demonstrates that time will proceed like the river.

Water, a central theme in the book, enacts all the ritual and reality of what it offers spiritually and practically. Here, water is our daily bread, holy and full of stories and sounds, beginnings and endings. From the opening poem, “Autobiography” the narrator, like the river, contains all things: “I was a failed skip of stone / sunk into the river for a moment I was the river / purling in long last shadows of September / for a moment I was a skinny grizzly spitting/ into a beer can for a time I was Christmas/ lights,” Miller writes. Before this poem, even, the book opens with “An Invocation to the Merrimack”—a summoning incantation, a prayer to the river’s life-giving force, its birth-like powers:

Miller’s is the poetics of the elemental nature of the American experiment; it is also an ecopoetics. Like the river, like e pluribus unum, we’re made of forces natural, spiritual, and historical.

While Miller’s poems are braided into a kind of historical garland, the structure of the book is sustained by the way history takes turns defining the river and vice versa. The art of recognizing these effects of history lies in observing the environment with the poet’s eye and recombining sediment-heavy narratives so that we can see the clear trajectory and force of human nature. The Beat poets, too, looked at the American landscape as an interactive environmental force of nature, as well as a dream to be conjured, a hope to be held, a history to be reckoned with. Our origin stories are always complicated, and poetry in the hands of Miller enacts this with both aplomb and growing reverence for the ways in which language and environment shape us.

Elizabeth A. I. Powell: A river and its bed is so evocative, so full of life, death, history, all moving with the force of water. It’s elemental. When poetry is brought to the riverbed it becomes archetypal, thick with the sediment of what was, what is, and what will be. This makes me think of how rivers are a part of us internally and externally, how nature and society help write our history into us through what happens by rivers, whether from the history of the Penacook to the Industrial Revolution on the Merrimack, to race relations, to the young poet considering the river in all its immensity. How have the facts of the river and the mill town shaped you as a poet? What drew you to knit the threads together? Tender the River is a kind of documentary poetry, to me.

Matt W. Miller: Catch the river on a September afternoon and you can’t imagine something more beautiful—and not just that natural beauty, but even the worn-down human creations, the way it reflects the redbrick of the mills, the oxidized green bridges. It’s mix of the eternal and the ephemeral. But the water is fierce—it floods, it whitewaters, it freezes, it is dirty with human junk, from chemical runoff to cars dumped in it for insurance scams. The force of the Pawtucket Falls dropping off so drastically powered us into the Industrial Age and all the good and bad that came with that. When I was a kid, it was just this pretty thing we went on school trips around, this thing that native tribes fished and gathered [around]—and then suddenly [there were] mills, and industry.

But of course the history was much more nuanced and complex, and there was a lot of suffering, but also joy. And both are part of its beauty and why I wanted to dip into it. There’s an energy along the river, from Manchester to Lowell to Newburyport. Lots of stories, lots of people telling stories, staying alive with stories, that pour from all these canals, brooks, and streams of experience into this big ole river, humming together until finally raging off into the sea, but vital for having existed during their time.

Yeah, I guess I was doing a kind of documentary poetics project without even knowing the term yet. I admired what [Tyehimba] Jess did with Olio and Leadbelly and Patricia Smith’s work on Blood Dazzler and a lot of what Jill McDonogh has done in her books. Hart Crane’s The Bridge was something I was really looking at when writing some of this.

EP: If the river dries up, it can come back. But what if it doesn’t? What if the river is too injured? What if human narratives have made it sick?

MWM: I mean, the river did not even cut through this part of the earth until the Laurentide ice sheet pushed it that way. It is really as transient as we are. What’s 15 thousand years to the earth, to the galaxy? But we speed up our destruction with its destruction. The hate we give it, to borrow from Tupac, fucks us up. The villainy we teach it, to twist Shylock, will better our execution. We have this desire to say, I was here and I mattered. We want our stories to live so that we live. There’s that idea in Mexican culture that true death is not when the body dies but when the memory of you dies, when your name is no longer spoken—read Ada Limón’s brilliant “The Three Deaths.” So we hold our lives inside our stories, for as long as that lasts. But ultimately it won’t. The end is inevitable. Ragnorak comes to all of us and will eventually take this river, this earth, the universe, the whole shabang a bang.

EP: There’s a desire for memory not to be washed away, and an insistence upon remembrance. Can you speak to that, the poet as a documentarian of a society seemingly meandering into continual collapse and regeneration?

MWM: You know, one thing I keep thinking of is the failure of this book. I wanted to get these stories and images and songs down, to document them and I just feel I came up short. There are stories I didn’t tell or wasn’t able to tell in a way that worked. People that should have their stories in here but that I couldn’t quite get in. But then the book would just be this massive thing that doesn’t hold together.

EP: In writing these poems was it your intention to revisit the archetypes of the river as a stay against confusion? Was the river the question or the answer?

MWM: Confusion is certainly our state. And the last few years seem to be especially confusing—but that may be me personally and us nationally being at the Dantean “mid-way through our lives finding the right path lost” [moment]. So maybe I reached back, trying to go home again to draw from where I strayed. There’s no narcotic stronger than nostalgia. That’s where MAGA found its power—getting people doped up on nostalgia for a time that never really existed. But the attraction is the same—if I could just go back and reset and see where I lost that thing I can’t name. But then I think of “hiraeth,” the Welsh word for nostalgia or longing for a place that no longer exists and maybe never did. In writing this I undid, for me, the myth of my Merrimack and my Lowell. I had to unfold it in a way. So the look back is an attempt to move forward. You have to recognize what the past really was to see a future, otherwise you exist in limbo, outside of time.

So maybe that is the stay against confusion, unpacking the myths and the glossing over of the past. Was the river the question or the answer? Maybe both? Maybe the river is like an essay, an attempt. It wanders where the land lets it and pushes through places where the land doesn’t, carving out its place until it finds an end. But the end is not an answer. Like really great essays, there are no answers, only better questions. Answers are just a horizon line we move toward but never reach but in the attempt to reach it we maybe find something of ourselves. And there’s something to being content with confusion, to have that Descartian willingness to exist in the doubts.

EP: There’s a kind of elemental spirituality of existence in this book that I admire very much, especially the poem “Legend” (one of my favorites), about the gym named after the grandfather who disappears. The speaker contemplates the meaning of how we live on in a place and that sometimes that place is memory. There is a kind of elegy for solidity in this poem, no?

MWM: Yes, for sure, nothing lasts, nothing is solid, as much as we think it will be. My grandfather was this legendary figure when I was growing up, a former all-pro NFL ironman for the Packers who became a hall of fame high school football coach and saved a lot of boys’ lives by giving them something to work for, to stay in school for. But already I know that legend is fading. So his story becomes a metaphor for how all of us, the whole human experiment, will fade away too. It’s all very Ozymandias, recognizing that our mighty moments are just that, moments, blips in the universe, a bubble on a river. The river wasn’t even there 20,000 years ago. It took the ice age to move and carve it in the direction it goes. And even that is such a short time ago, geologically. But that is also why it’s so amazing, the whole “death is the mother of Beauty” thing, I guess (and Willie Perdomo might remind us to ask who Beauty’s father is). Our short moments of existence, our brief crack of light between the darknesses, to borrow from [Vladimir] Nabokov, make that light so incredible. It’s why the gods envy us: because we die, and that makes our lives beautiful.