Andrei Codrescu’s New Orleans

The vignettes in Andrei Codrescu’s New Orleans, Mon Amour make it clear that the writer not only loves the place, but knows it intimately. Codrescu left Romania in 1966, and settled in Louisiana. The book’s tone is by turns sensuous, dreamy, brusque, sarcastic, and pensive. It captures the mood of the city, shuffling familiar New Orleans tropes into fresh arrangements. In his introduction to New Orleans, Mon Amour, Codrescu writes of arriving in the city: “I caught the Mythifying-of-New-Orleans virus, too.” In southern writing, the difference between self-conscious mythifying of a place (as in Codrescu’s vignettes) and wide-eyed sentimentality is easily felt. Still, it’s difficult to parse what exactly makes the difference. Perhaps recreating a living, breathing place on the page has to do with living there long enough. Or perhaps it has to do with an author’s willingness to look frankly but lovingly at a familiar place. Codrescu’s work captures his southern city with nuance and playfulness, even as he questions the value of classifying authors by the places they write about.

Codrescu’s writing is a good cure for sentimental wistfulness. The poems in his collection it was today are breathless, biting, filled with coffee, cigarettes, naïve young poets, hangovers, babbling televisions, and sex. They’re not particularly regional poems: they deal with migration. “a geography of poets” begins: “what poets now live / where they say they do / where they started out / where they want to.” Trying to pin down poets based on region is foolish: “half the midwesterners / did time in california / the other half in new york.” Though Codrescu doesn’t explicitly mention the South, this anti-geography is true of those considered “southern” writers as well: Carson McCullers lived in New York and Paris; Flannery O’Connor spent years in Iowa and Connecticut; Robert Penn Warren was educated in California and Britain. For these writers, Codrescu’s words seem apt: “this is america / you get hurt where you are born / you make poetry out of it / as far from home as you can get / you die somewhere in between.”

For old-school southern writers, it seems, having roots in the South—being born there—is a key reason they’re classified as “southern writers.” Thinking of contemporary writers like Codrescu as “southern” is more complex. Though often intensely regional, movement is a central concern of his essays and poems. The structure of New Orleans, Mon Amour is itself restless, dynamic. Many of the essays are brief, showing the reader a vivid, haunting image, a wisp of memory, and then jumping to a different scene across town. Within each essay the reader feels the tug between natives and tourists, the familiar and the shocking, routines and disruptions. These are everyday tensions in all cities, not just New Orleans. But there’s also the author’s evolving relationship to New Orleans, and to the South. In “South,” he writes:

I am of the school that maintains that migration is good for the soul. I believe with the Hopi Indians that one must cross the earth up and down and sideways before finding one’s center. I have lived in the East, the West, and the North. The South is a personal necessity, even if it weren’t for its ancient fascination.

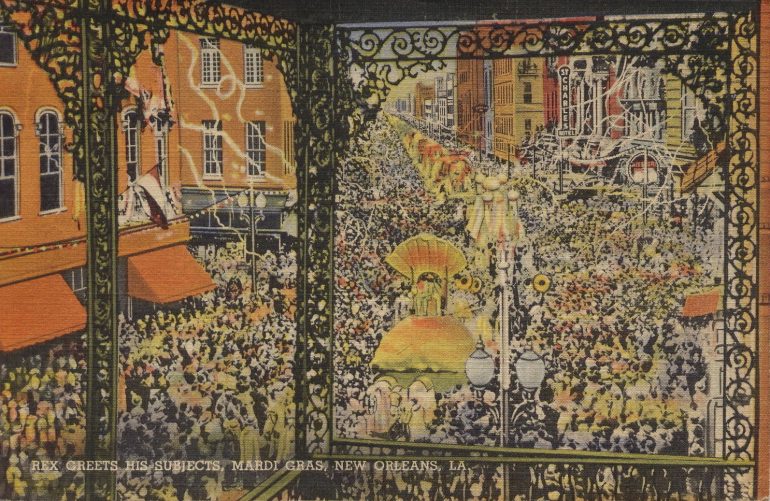

This is a southernness that’s different than the easy authority of a southern-born writer. It mixes deep knowledge with an observant distance that is never entirely collapsible. Tropes have a place in Codrescu’s essays, but they don’t feel treacly. He returns to images of New Orleans that are familiar even to those who’ve never been there: café au lait and beignets, Mardi Gras, mud, heat, sweet-scented air, magnolias. But Codrescu rearranges these images, makes them surprising with piercing specificity. In New Orleans, Mon Amour are several essays about the seasons, and though writing about regional weather is an easy route to cliché, the weather in Codrescu’s New Orleans is so vivid you can feel it on your skin. From his essay “Hint of Fall”:

Most of you, used to big fat red and yellow leaves and brisk winds smelling of apples, wouldn’t recognize it. But here in the deep deep South in the dreamy mud of the riverbend at New Orleans, we do know it. It’s only a change in the light, a knifeblade-thin change from bright white to reddish. It’s only a sweat drop’s difference in dryness.

“Hint of Fall” is about how the soul of New Orleans compares with that of the rest of the country: “People elsewhere produce. We exult, admire, celebrate, reproduce.” This is what I like about regional writing: it captures the “knifeblade-thin” changes in a place, the corners tourists and literary clichés probably miss. Codrescu’s model for effective regional literature isn’t nativity: it’s motion. Or, as he suggests in “South,” disorientation. Like “South,” “geography of poets” end with an image of generative lost-ness: “some of us came from very far / maps don’t help much.”

Still, if you move too much, you miss what’s particular to the places you go. Especially if you move only to capitalize on the places you visit. In “Cult Extra!” Codrescu goes to a cemetery “to sit and think.” Instead of peace and quiet, he finds himself on the set of a film shoot. Codrescu condemns Hollywood on account of its constant roving and devouring. “I speak of Hollywood, the roaming monster of illusion, which is taking its hydra-heads on the road and sucking character out of places.” Though Hollywood can replicate place, they can’t get it quite right:

The oaks need more moss, the mansions need more spookiness, streets should bear other names, the people aren’t quite right, either. Very soon, houses are fixed, street names changed, moss added, real people replaced by actors. At last, the place is perfect! But it’s a stage set and nobody can live in it.

Perhaps this is the test for honest regional writing: descriptions should reflect places where people can live, and more importantly, where they do live. In Codrescu’s New Orleans, folks sweat, drink, dance, fight, walk under gardenias, smell the mud. The place is alive because they are, and vice versa.