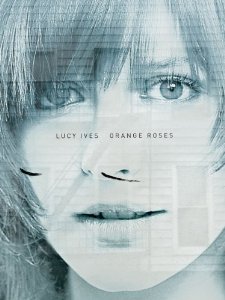

Orange Roses

Orange Roses

Orange Roses

Lucy Ives

Ahsahta Press, September 2013

104 pages

$18.00

With the proliferation of graduate programs in creative writing, the day approaches when most poetry published in the United States will have been written by people with graduate degrees in writing poetry—a prospect that may launch a thousand jeremiads. But I will not complain, so long as the academicization of American poetry means we will be getting more books like Lucy Ives’s Orange Roses.

Ives’s poetry is aware of its own processes—as in “Early Poem,” which enumerates its one hundred sentences as they occur (“In the thirteenth sentence I realize I have chosen something”). It is also aware of its own awareness of its own processes, as when the eighty-third sentence forgets to count itself, prompting the admission, “sentence eighty-four contains the question, didn’t you already know that this would start to happen.” For some, this will seem like disappearing down the meta-poetic rabbit-hole. But the rabbit-hole, remember, is one of the ways to get to Wonderland.

Ives, in one of her modes, is indebted to the William Carlos Williams, who declared “no ideas but in things,” and to the Objectivists like Zukovsky and Oppen, their influence discernible in the paratactic strings of brief, precise images (“A cup of orange drink in his / Left hand; the flag on a string”). In another of her modes, she wonders what that debt means to her, what it may have paralyzed, what it may have enabled: “My understanding of writing was for a while informed by an idea about insufficiency I got from America,” she writes in “On Imitation.”

The most striking piece in Orange Roses is, in fact, “Orange Roses,” a poem that is almost an essay, or an essay that is almost a poem, or perhaps a journal in which Ives wonders what her writing can or ought to do. She values fiction’s attention to the ordinary, but “an interest in what seems to be the case precludes my accession to a purely fictional form.”

Yet poetry poses its own conundrums. If we insist (with the Objectivists) on the present, then we find that “the present is whatever must be alleviated by a message.” But one cannot compose a message without a clear idea of its recipient, and there again Ives feels an impasse: “I have never known how to write poetry. It is not a question of relating language to a person one is but rather of relating it to the exact person one is not.” The text does much more than circulate around such theoretical questions, however; its anxiety is leavened with humor, lyricism, ingenuity, and wonder.

An Ives poem, “The Country House,” appeared in Ploughshares in the Winter 2001-02 issue. Lightly revised, it appears in Orange Roses, but here it is titled “Ploughshares.” The gesture of that re-titling repeats the choreography of the whole book, in which a maturing writer looking back on her younger self with a kind of wild surmise, amazing herself by where she has been, and amazing us by where she might go.