Other People’s Paperbacks

I have outlined here before the likelihood of writers finding value in old objects, as to me, there is something storied in a weathered possession. I make no exceptions for other people’s paperbacks. Give me your tattered Jane Eyre or marked-up Cather. Your well loved or out of print. Or better yet—don’t. I may be operating at capacity.

Recently, I was stopped in standstill traffic near Truro Beach on the Cape, when I saw a hand-scrawled sign: Estate Sale. So I steered my car down the shoulder of the road and took one of those unlikely side streets, the ones that snake across the tall dunes and meander toward the fog-covered ocean.

There, I found a historic white house, paint chipped, and a shingled barn with its doors flung open. Mismatched china balanced precariously on card tables, surrounded by boxes of coffee-stained lace and linens.

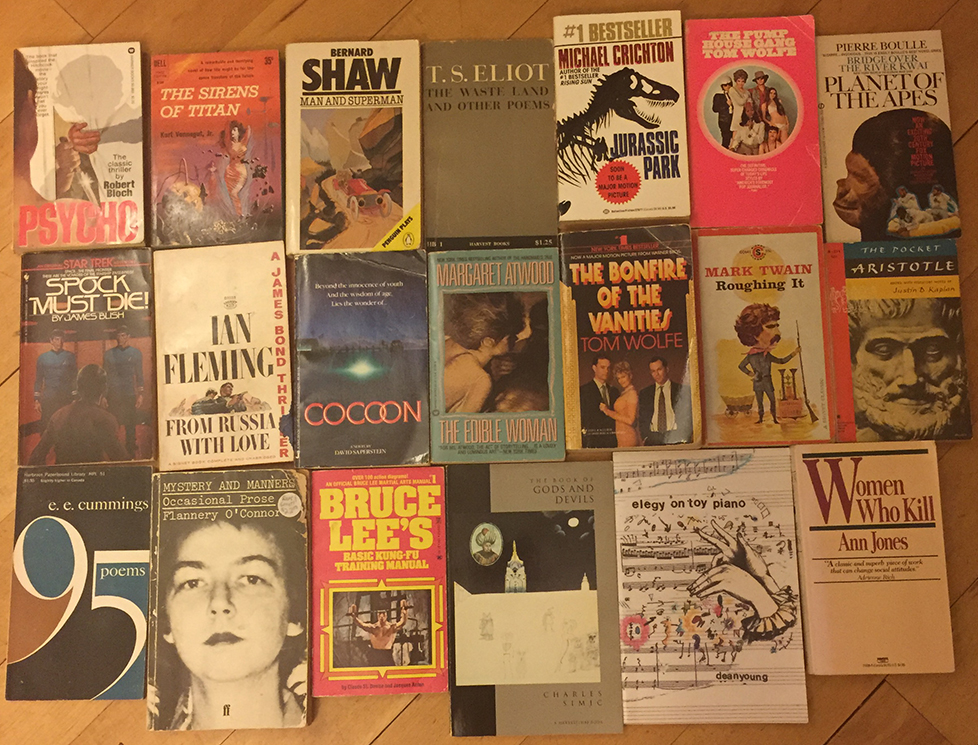

Show me the books, I thought, and then I spied them: four crates of paperbacks and art books. In roughly five minutes, I had an armful so high that I could hardly see over the stack. That is usually how I know it’s time to pay, and I make my way to the person with the cash box, spilling my finds as I go, recollecting them.

My spoils: two Henry Millers, a bizarre 60s paperback of Camus’ The Stranger, and some D.H. Lawrence, one of which had a vibrant hot pink matte cover.

“My father and I did not share the same taste in books,” the woman said.

I raised an eyebrow. I felt defensive. Was I going to go head to head with this woman on literature, here on a sand dune? These books aren’t dirty, I started to say.

But then she rescued us both. “I’m just glad they’re going home with someone who can appreciate them,” she said.

I nodded, righteousness easing. All too often—evidenced by my sagging book shelves—I have a desire to rescue an item I find full of worth and intrigue from the trash pile. Or, in one vivid instance, my husband’s attic, where, neck deep in a purging project, I discovered the slimmest and most fascinating paperback: Annie Dillard’s 1977 Holy the Firm. The cover proclaims it is “a journey into the beauty and violence of life.”

I happened to find it right before a camping trip. Always one to underline inspiring prose, I nearly underlined the entire book. Holy the Firm is one of those books that defies expectation. Apparently Dillard aspired to write whatever came to her during a three day period on Lummi Island. After a plane crashed on the second day, this eighty page meditation on pain and “natural evil” spilled forth.

“I praise each day splintered down, splintered down and wrapped in time like a husk, a husk of many colors spreading, at dawn fast over the mountains split,” she writes on the first page.

For a short story writer hacking away at her second book, Dillard’s inventive, philosophical, and potent book was a glorious shot in the arm. Medicinal.

Discovery is healthy for writers. My advice is this: read other people’s paperbacks, especially the ones they held on to, marked up, and aspired to hand down to unsuspecting heirs.