Poet Activist Spotlight: Jacqui Germain

Taken at the Movement for Black Lives #M4BL Convening in Columbus, OH (2015)

“Imagining a radically liberatory world is creative work.” —Jacqui Germain

Jacqui Germain, a poet based in St. Louis, MO, is a Callaloo Fellow, promising political essayist, and remarkably visionary young public intellectual and activist. At Washington University she’s worked as a student organizer in the Black Lives Matter protests against the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson and the subsequent non-indictment of Officer Darren Wilson. She has also represented Washington University at St. Louis on multiple National Poetry Slam stages at the collegiate and adult levels and coached Washington University’s 2016 CUPSI (College Union Poetry Slam Invitational) team.

I first became aware of Jacqui Germain through her widely-circulated poem, “Conjuring: A Lesson in Words and Ghosts.” which was first published by Muzzle Magazine in 2014 and went on to be included in Sundress’s annual Best of the Net Anthology. The speaker of this poem interrogates the moment of a young black woman sitting in a college English class in which a white professor chooses to say the N-word. The defense that “he only read it in context” is weighed against the context of “black people hanging off the g’s .” Germain reckons with white academia’s privileged oversight of black ghosts and gives voice to the isolating experience of being gaslighted for seeing those ghosts swarm in a room clanging with old rhetoric: “& don’t tell me I can’t say that word but you can & be mature…”

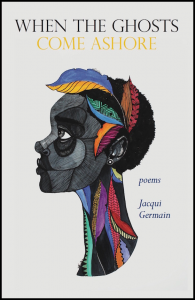

Jacqui Germain’s recently released chapbook, When the Ghosts Come Ashore (Button Poetry, 2016) bears the weight of the ghosts of “ black boys disappearing right /out of the like a shut / mouth,” yet insists upon a stubborn joy particular to having “survived so much / that no one remembers.” St. Louis is embodied and given a mythic voice of defiant resilience: “You think I cannot speak, / but I just choose not to speak to you.” In these poems, the most unkillable thing seems to be the voice of dissent, which is sharp-tongued and resolute. Perhaps my favorite poem (and poem title) in the collection—“How America Loves Ferguson Tweets More than the City of Ferguson (or Any of the Eighty-Nine Other Municipalities in St. Louis)”—responds to the narrowed outrage around the shooting of Michael Brown “that doesn’t mention / St. Louis, but will / win an award for how the photo /makes taxidermy of our trauma.” With When the Ghosts Come Ashore, Jacqui Germain presents speakers haunted by American violence and speakers who haunt back, alongside the quiet vibrant solace held in the will to “still /open wide for the sun.”

Q&A with Jacqui Germain:

Stevie Edwards: How do you see the relationship between your work as a poet and as a community organizer? Does one feed the other (or, perhaps, are they symbiotic? or something else entirely)?

Photo credit: Lindy Drew

St. Louis Students in Solidarity action blocking an intersection near Washington University in St. Louis (November 2014)

Jacqui Germain: For now, I think I see both roles as somewhat facilitative. I don’t even know if she remembers this, but Patrisse Cullors-Brignac said once (and I’m paraphrasing) that the job of the organizer is to facilitate space for the community to show up and be brave. My role as an organizer is to facilitate opportunities for growth, to disrupt narratives in order to correct them, to offer strategies that subvert oppressive powers, etc. Organizers create and sustain space for communities to access their own power. My work as a poet attempts to do something similar. I’m invested in writing poems that challenge hegemony, that complicate and question the world as it’s currently organized, because as is, it’s killing us. Daily. I think poems that are deliberate and relentless in their attack against dominant powers and the narratives they push are capable of facilitating radicalism in the same way that organizers do, just remotely. My work as a poet and as an organizer is not to tell the reader or a community what to do or believe; my job is to give you the opportunity to question what you already do.

SE: Are there any poets, past or present, whom you particularly admire both as writers and as activists (or creators in other genres)? I’d love to hear about your influences.

JG: I love Franny Choi’s work, for so many, many reasons. She and I actually got to talk about her organizing work for the first time a few months ago, but I’ve been a fan of her poetry—written and performed—for a long time. To me, it’s clear from her writing that her resistance operates on multiple planes—whether in her geographic community, online, or in the literary field. She’s so careful with her word choice, her syntax—all of it. I admire the intention with which she writes, and I’m sure she’s just as intentional of an organizer in her communities. Ariana Brown is another writer I adore; her resistance is evident in her poetry, which is particularly deliberate and precise. Her attention to history and how empire has shaped it translates into poems that refute historical narratives that privilege the oppressor in literally every line. Interrogating history is significant work. I didn’t realize poems could really even do that kind of valuable retelling until reading her work. I’m thinking of her poem “Ossuary” in particular, but she has plenty to choose from. I’ve never met anyone who moved through the world like she does, but she and her writing are both powerful forces in service of resistance.

Also I use the word “deliberate” a lot. In this context, and with both Franny and Ariana, I mean “deliberate” in that they don’t deal in these large, looming abstractions about violence and oppression. So like, instead of just telling me that a knife is sharp, they pick up the knife, sharpen it, and then dare me to touch it. Their poems are catalysts for the political, cultural and historical work necessary to imagine and create a radically new world.

SE: I’m sure I’m not the first person to tell you this, but I found your article in Salon, “Faith After Ferguson,” very powerful, particularly in its visionary capacity in the face of events that “could indeed melt any person down into an utterly disenchanted nihilistic cynic.” Toward the end, you write, “I have faith in the capacity of the collective, in our own futuristic brilliance and knowledge of history.” I was wondering if for you this faith in the collective’s “futuristic brilliance” relates to your need for creative practice and creative community?

JG: Oh, certainly. Imagining a radically liberatory world is creative work. Planning and executing a successful direct action is creative work. And that’s a big part of how we sustain ourselves. Flying Lotus’ video for “Never Catch Me” is futuristic brilliance that helps me not fall apart, even on the hardest days. Artists who engage in that creative practice, people who invest in the creative communities who feed that creative practice—all of it is essential to our survival. The “futuristic brilliance” that I mentioned is just creativity in service of liberation. And just because there are many ways to be in service of resistance work doesn’t mean that anything you do that’s creative is necessarily in service of resistance. There is a deliberateness required—and there’s that word again—that I’m hungry for, as a writer. And I’m most drawn to creativity that cares to be deliberate.

SE: Although poet activists—and more broadly, artist activists—are not a new tradition, it seems there’s somewhat of a renaissance happening now. Do you have any thoughts on what’s propelling this new wave?

Photo credit: Clark Randall

Taken in downtown St. Louis (December 2014)

JG: This is maybe one of my favorite things to talk about, the shift in energy taking place in multiple artistic fields right now. We can see it musically, I think, even before the latest releases of songs and statements from celebrities. But I notice it a ton in the literary field, which is still a pretty new space for me, and that’s where I think it’s the most exciting. I think the new wave is the same old wave of writers of color trying to navigate the world, but there’s been a build up of violence and erasure and frustration and this and that and so many other things that are coming to a head in an era where access—because of the internet, new literary journals and lots of other things—and identity are both being renegotiated in some truly, dramatic ways. Poets my age are also historians. Poets my age are community organizers. Poets my age are high school teachers. So many of us are operating on multiple planes at a time. When those planes are intersecting rapidly, which I think, means the concepts we’re struggling with across the literary landscape aren’t new, poets in this generation have the tools to turn those concepts on their heads, ram them up against other things, peel them open and expose their insides. There’s a very deep-seated interrogation happening right now, and it’s birthing a lot of really brave shit. It’s not new shit, but it is brave and, of course, deliberate. So it’s the same wave, but the wave is cresting and it’s going to hit the shoreline soon. I can feel it.