Poetry Dialogue: Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon

Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon is the author of Black Swan (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2002) which was a winner of the 2001 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, and ]Open Interval[ (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009), which was a finalist for the National Book Award and for the L.A. Times Book Award. Her work has appeared in many journals including African-American Review, Callaloo, Crab Orchard Review, Gulf Coast, and Shenandoah, along with the anthologies Bum Rush the Page, Role Call, Gathering Ground, and The Ringing Ear: Black Poets Lean South. She is an associate professor of English at Cornell University and is currently at work on a third collection, The Coal Tar Colors.

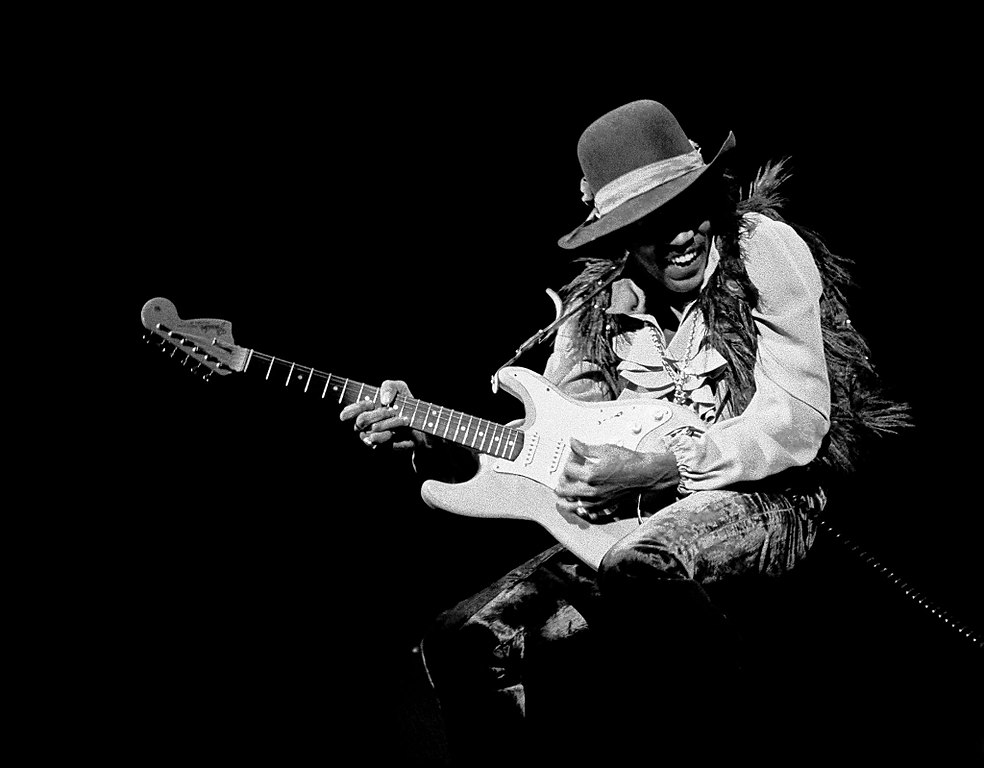

The dedication from Lyrae’s stunning collection, ]Open Interval[, is a quote from Jimi Hendrix’s “Castles Made Sand”: “…and it really didn’t have to stop / it just kept on going… ” Fans of Hendrix’s music (or those who followed the previous link) might remember the coalescing of feedback and backwards looped guitar in the song while he’s making his observations. One of the great things about that moment in the song is the music itself embodies what the word “feedback” implies. It seems as if the only reason the song has to stop is because the tape ran out.

The allusion to Hendrix’s endless loop of sound and sense sets up one of the ways ]Open Interval[ can be read. The poems in the collection create loops: of astronomy, of art, of the body, of connections between the self and others. It is through these loops that the collection’s title takes shape.

Like an open interval, a loop doesn’t have endpoints necessary. It is defined by understanding the things, real and implied, around it, as in the poem “RR Lyrae: Supernova”:

You love this opening riff— as much as I—

My emptiness— like that of a guitar—

An instrumental hollow—: In the sky

(Where else?)— diminishing’s an art—: The star…

Or again in the poem, “Black Hole”:

my darkness is not hell

but darkness darkness

is naked and original

is not darkness but

density…

“Black Hole” has a terrific epigraph from C.K. Williamson: “Poetry exists.” The epigraph is appropriate, not only for the poem, but for the collection. Because of the way Lyrae utilizes the page and manipulates punctuation outside of poetic convention, her poems have a tactile sensibility. They exist both physically and intellectually, even if we need the language of astronomy or the feedback surrounding the loops to help guide us on occasion. In this way, the poems in ]Open Interval[ are like the very stars they sometimes allude to, bright with em dashes and human need.

With that, here’s my conversation with Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon. This conversation took place via email at various points between January 18, 2011 and February 15, 2011. There is more to this dialogue, but because of time constraints, the rest will follow in a later post.

Adrian Matejka:

At AWP in 2010, you and I participated in a free-form panel discussion about culture and aesthetics in poetry that really got into some serious business about cultural expectations. As part of the discussion, you talked about banjos and how the instrument is African in origin. That fact still blows me a way. Co-opting is part of colonialism, but there’s usually a fight. Attempts to co-opt jazz, Jimi Hendrix, Public Enemy, and hooded sweatshirts were met with all kinds of resistance. But the banjo? It seems as if it got appropriated without a fight. Which is strange since I’m listening to Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings right now and the banjo is a big part of the rhythm section in these recording. Why don’t people associate the banjo with its African roots?

Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon:

It was great to go down to the 2010 Black Banjo Gathering (at Appalachian State in Boone, NC) and see folks like The Carolina Chocolate Drops and Otis Taylor, who did that Recapturing the Banjo album, and others who are passionate about the instrument. There are folks still fighting. Though I’m not sure that’s even how I’d put it. There are people who love the instrument period and that makes me happy, because I love it too. I love the sound of the thing and the look of it and the feel of it. I’m certain some folks get warded off by blackface minstrelsy images, of course. Those images, and what’s behind them, interest me so much less than the absolute gorgeousness of Henry O. Tanner’s The Banjo Lesson. Or, better yet, images I’ve found in my research of black women with banjos.

AM:

I know the Tanner painting you’re talking about. It is really beautiful. Romare Bearden’s work also included banjos without the other connotations. Three Folk Musicians and Uptown Sunday Night Session come to mind first. His work seems to recognize the banjo as part of the cultural catalogue. Not out of place, just misplaced. You’re right about the connections to minstrelisms, though. I think the banjo has some historic reshuffling, to put it mildly. My stepfather played banjo vigorously until my little brother tried to treat it like a guitar. He was doing some kind of head-banging thing and accidentally broke the banjo’s neck. Was that just my brother’s ham-fistedness or is the banjo an instrument of delicate sensibility? Physically, it looks more sentimental than the guitar or the bass. Sonically, its sounds remind me of trochees and alliteration. What does it remind you of?

LVC:

It’s a synesthesia thing—the banjo reminds me of my house. More specifically, the colors in my house—which are the colors in Romare Bearden’s Falling Star, those warm pinks and oranges and reds, (my writing space is a color called Russet Rose; my family room’s magenta) with splashes of turquoise. The drone string’s like turquoise. Banjos remind me of quilts, and warmth, and black women’s bodies. The manuscript I’m working on right now, The Coal Tar Colors, in part grew out of the fact that when I look at Eldzier Cortor’s Southern Gate (which I’m really hoping to use as the cover when the book’s done), I see a gourd banjo in the body of the nude black woman in that painting. There’s a throatiness to the notes, but a brightness too. It’s complex and seductive, but there’s a way in which, when I hold the instrument it just makes sense.

This is Adrian’s tenth post for Get Behind the Plough.

Image: Banks Hendrix (Steve Banks, 1968)