Postcards from Unexpected Places

Like long handwritten letters and atlases, postcards descend from another world now deemed impractical. They belong to the world of Denis Breen in James Joyce’s Ulysses and Loyal Blood and his travels across the American West in Annie Proulx’s Postcards. Ruth, in Lorrie Moore’s story “Real Estate,” finds the form “so careless and cheap.” The genre prizes itself in brevity, in its ability to simply telegraph a person’s self-defined whereabouts.

In Amy Hempel’s road trip story “Jesus Is Waiting,” a woman drives away from home and sends postcards bought at a rest stop to an old lover. All the cards ask questions about symptoms of a mysterious disease, and, in the end, all questions are left unanswered. The narrator doesn’t have a destination and neither do the cards. “God, it’s an ugly road,” she says at one point. But the postcards only show the manicured version of the real thing.

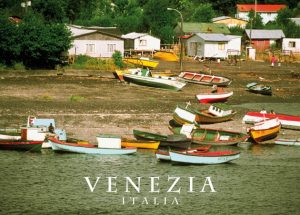

For the 2009 Venice Biennale, Swedish-American artist Aleksandra Mir created a series of postcards of bodies of water all over the world, with “Venezia” in colorful lettering superimposed on the photographs. None of the photos showed Venice, but all of them showed Venice to the untrained eye. Mir’s project, titled Venezia (all places contain all others), reveals that water is just water, regardless of borders or tourist appeal.

As Susan Sontag suggests, we often prefer the photograph to reality, the appearance before experience. Postcards offer a standardized image instead of the distinct sense of place. The constructed tourist sight is detached from lived experience, a vague reminder of the idea of a place removed from its context. The pictures are appealing, but they don’t say much. Perhaps, it’s the personal message in the back that must reveal the relationship between the traveler and the world of the image. The written note can communicate something as simple as “I was here once” and as personal as “this is a memento of my vision.”

My favorite literary postcard is from W. G. Sebald’s On The Natural History of Destruction, which defies the superficiality of the genre. The postcard of Frankfurt shows two grainy images of the city in 1947 and 1997, “yesterday and today” — one shows the destruction caused by bombings during the war and the other shows the city’s subsequent reconstruction on top of the ruins. The images by themselves say nothing, but the juxtaposition exposes their powerful contrast and historical effect.

Perhaps postcards best capture a nostalgia inherent to the passerby. Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri, who collected postcards, describes the confining experience of driving through the country: “Melancholy is the road sign for an effaced geography […] Because the horizon nearly always mingles earth and sky, because the countryside also inhabits city and villages, because streets seem always to head toward the same point – and thus to nowhere.” Ghirri once said in an interview that a landscape and its representations become the same thing, eventually. “Reality is becoming more and more like a giant photograph,” he said. All waterways lead to Venice and all roads lead to Rome.