Quiet Behind the Waterfall

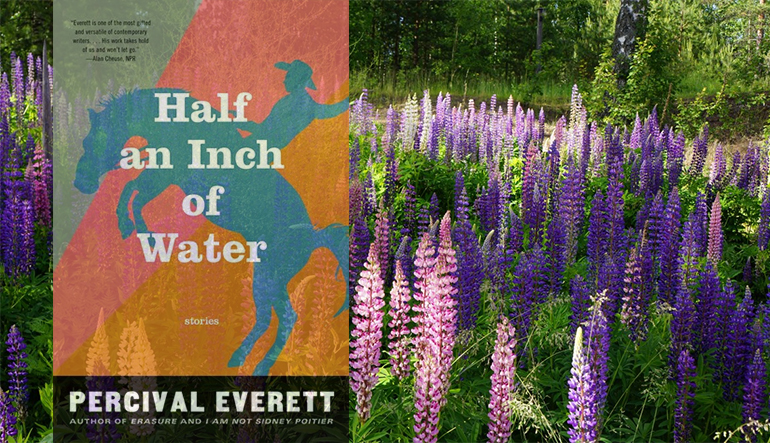

Percival Everett is the author of around thirty books and his subject matters and genres range across a giant gamut. He has published novels, poetry collections, and short story collections. The most constant mark of his work remains the quality of the writing, his sense of humor, and the deep compassion he has for his characters. In one of his more recent story collections, Half an Inch of Water, many of the stories are magically real: strangeness happens in hints. However, in one pitch perfect story that evidences some of Everett’s best writing qualities, the magic bubbles to the surface in thrilling ways.

In the story “A High Lake,” the elderly widow Norma Snow insists on riding her pony daily and living by herself despite age and severe osteoporosis. Norma is cranky but kind, as evidenced by her interactions with her neighbors who occasionally visit and the nurse she’s hired to check on her daily to make sure she hasn’t fallen. During one of Norma’s rides she gets lost tracking an animal’s path and comes to a waterfall. She pushes herself, and her pony, to go through it and they end up in a meadow “filled with fairy trumpets and purple lupines and newly bloomed chickweed. She could see firewood crowding a slope in the distance. The flowers didn’t make sense altogether, and the chickweed should have been long gone.” Not only is the foliage confusing, but Norma soon is greeted by what seems to be the youthful version of her beloved, and deceased, German shepherd.

Within this space of strangeness, we learn a little more about the losses of Norma’s life. In one beautifully moving passage, Everett shows what the shape of a long lived life can hold:

She imagined trout in the water below her. She imagined the whistling of her husband as he fished. She imagined the footfalls of her daughter coming up the hill behind her. She tried to smell her. Somehow she knew that if she smelled her child, she would be real.

Norma eventually leaves the meadow, realizing people would be out looking for her, worried. And she finds there are many people who have come out to help look after her, she sees the amount of concern for herself—from neighbors, her nurse.

Once back at home and set up in front of a warm fire, she tries to piece together what happened to her: “She could not remember the place she had visited well enough to describe it to herself. She only knew that she had been there. She remembered the dog. She remembered the warmth.” Like in the fairy tales about people who visit paradise or the land of faery, Norma finds it something that is both more and less than a normal memory. As the story ends, we’re left with the image of Norma, sitting in for of the fire, feeling herself grow warmer and the story ends, “the fire grew cold.”

There’s a few ways to read the ending and none of them are sad in the way that a reader might expect. Everett creates a depiction of being at peace with old age and surrender that feels as warm as the fire and meadow he describes—a place where youth is restored to an old, loved pet and the sun doesn’t set. This is a story that should feel dripping with treacly sentimentality and yet it doesn’t in Everett’s hands. Everett stuns not only with the clarity of his writing and imagery, or his deftly created characters, but also with the way he leaves some moments unsaid. A skill he uses throughout his body of work, he trusts his readers to know what to take from the stories he is telling us. Because Norma is never quite sure if what she is experiencing is real, or if the dog she greets is truly her long lost pet, the reader doesn’t know whether to believe it either. It’s in that space between belief and disbelief that the magic of this story lies.

About Author

Chloe N. Clark's work appears such places as Apex, Bombay Gin, Booth, Midwestern Gothic, Sleet, and more. She can be followed on Twitter @PintsNCupcakes