Review: HERE I AM by Jonathan Safran Foer

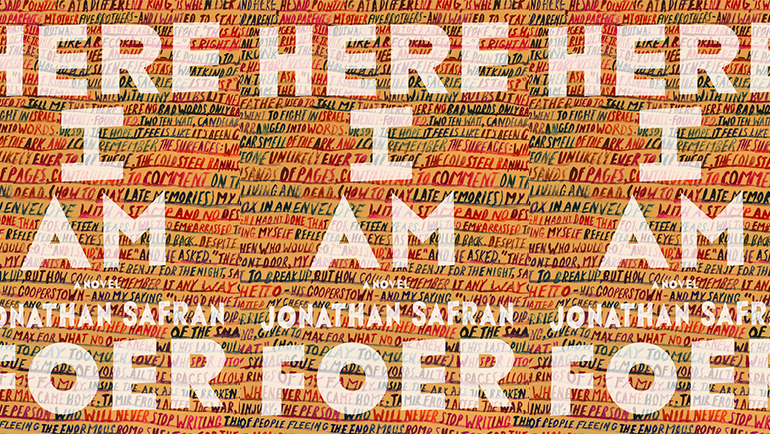

Here I Am

Here I Am

Jonathan Safran Foer

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Sept 2016

592 pp; $28

In the age of social media and personal branding, book reviews tend to focus as much—if not more—on the author’s life as they do on the book in question, and Jonathan Safran Foer’s third novel seems to have garnered as much attention on his life in the last decade as it has on the book he wrote within the last few years. As if anticipating this, or fueling speculation, Jacob Bloch in Here I Am has a secretly-written a show based on his own life: “Should he one day share it and be asked how autobiographical it was, he would say, ‘It’s not my life, but it’s me.’”

Readers of Everything is Illuminated and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close may recognize themes of family, lineage, and identity backdropped by catastrophe. Foer’s first novel, written decades after the Holocaust, featured a character named Jonathan Safran Foer traveling to Ukraine to learn about his grandfather, who survived the genocide. Oscar, the young narrator of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, searches the city for a trace of his father, who died in the World Trade Center attacks on 9/11.

Both novels sifted through the resonances of unfathomable events, while Here I Am is rooted in the present and possible future—one in which a couple considers divorce, boys grapple with what it means to be a man, a patriarch nears the end of his life, and a catastrophic earthquake strikes Israel. Divorce, death, and natural disaster never occur neatly, one at a time, but come all at once. Each precipitates the question: what kind of life do we want to live? And: what is home?

For Jacob and Julia Bloch, home is a house in Washington DC where they raise three young boys. In the same passage as “It’s not my life, but it’s me,” readers are given a succinct sketch of the characters in Jacob’s secret screenplay, which mirror those in the novel: “an unhappy wife (who didn’t want to be described that way); three sons: one on the brink of manhood, one on the brink of extreme self-consciousness, one on the brink of mental independence; a terrified, xenophobic father; a quietly weaving and unweaving mother; a depressed grandfather.”

Neither Jacob nor Julia Bloch are happy in their marriage. Their eldest son Sam would rather play—excuse me, live—in the digital environment of Other Life than have a bar mitzvah. Max has reached the age where one begins talking back to their parents in sometimes-profound, mostly-snarky ways (asked if he knows Hamlet, he responds, “I’m ten, I’m not unborn.”). Benjy is still figuring out the workings of the world, asking “why” quite often, and preferring to eat “unrealized foods” like still-frozen burritos or uncooked ramen. Jacob’s father Irv is often on a diatribe, and at the opening of the book, Jacob’s great-grandfather Isaac, a Holocaust survivor, “was weighing whether to kill himself or move to the Jewish Home.”

Though less visually experimental than his first two novels, Foer’s prose is equally ambitious. There may not be pictures, empty pages, or words printed atop words, but the novel plays with structure and forms, borrowing from chat rooms, text messages, and nonstop news feeds. The previous two novels were written before the proliferation of smartphones and smacked of a different era, whereas Here I Am seems sincerely of the now. Rather than shy away from the pervasive presence of the internet in our daily lives, Foer confronts it: an Uber waits outside the front door, while kids Skype with grandparents, bury themselves in their iPads, and seem to spend more time in virtual reality than reality-reality.

The character-driven commentary on our modern world and its digital accoutrements adds a sharpness to Foer’s writing—one that wasn’t there in previous works. When Sam meets his Israeli cousin Noam in a chatroom, Noam mentions that his father Tamir—visiting the Bloch family in the US—emailed him a picture of a plate of salmon. Sam asks why, and Noam responds: “Because it was there. And because the world lacks reality for him until he photographs it with his phone.”

As with much of Foer’s prose, phrases are at once funny (because they are true) and sad (because they are true). Just as Julia and Jacob parent as a “dichotomy of depth and fun”—representing “heaviness and lightness,” with Julia bringing the “gravity” and Jacob providing “bubblier, dumber activities”—the novel balances both, oftentimes within the same sentence or conversation. There’s an urgency to the writing, especially in dialogue, where characters possess a frenetic drive to understand and be understood:

“You must have fallen,” Julia said.

“Why?”

“There is literally no boo-boo.”

“Because falling is part of life,” Julia said.

“It’s the epitome of life,” Max said.

“Nice vocab, Max.”

“Epitome?” Benjy asked.

“Essence of,” Deborah said.

“Why is falling the epitome of life?”

“It isn’t,” Jacob said.

“The earth is always falling toward the sun,” Max said.

“Why?” Benjy asked.

“Because of gravity,” Max said.

“No,” Benjy said, addressing his question to Jacob. “Why isn’t falling the epitome of life?”

“Why isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“I’m not sure I understand your question.”

“Why?”

“Why am I not sure that I understand your question?”

“Yeah, that.”

“Because this conversation has become confusing, and because I’m just a human with severely limited intelligence.”

Pithy prose devoid of dialogue tags carries on for pages. Reading the Bloch family’s back-and-forth volleys is like watching Olympic-level ping pong: at a certain point, you stop being able to see the ball. The trail of who’s speaking to whom is almost imperceptible, in a way that conveys a connection that can only occur with kin.

But what is that connection? Is it rooted in a place, or in our blood? As the Bloch family discusses separation, the family patriarch considers death, and the Israeli relatives face the potential destruction of their nation, questions of home and identity arise. Yet there is too much happening here to assign Here I Am to reductive categories like a “midlife crisis novel,” which only trivializes its existential and emotionally resonant scope.

Jacob asks, “What’s so wrong with making good-enough money, eating good-enough food, living in a nice-enough house, striving to be as ethical and ambitious as circumstances allow?” These questions don’t pertain to a certain demographic—they transcend age, and those over forty aren’t the only ones who have earned the right to ask them. Though it asks the questions, Here I Am is not here to answer inquiries, eschewing easy answers or clean endings. It may not be a manual for life, but it is a way of locating oneself in the world.