Satire as Survival: The Necessity of Humor in Turkey Today

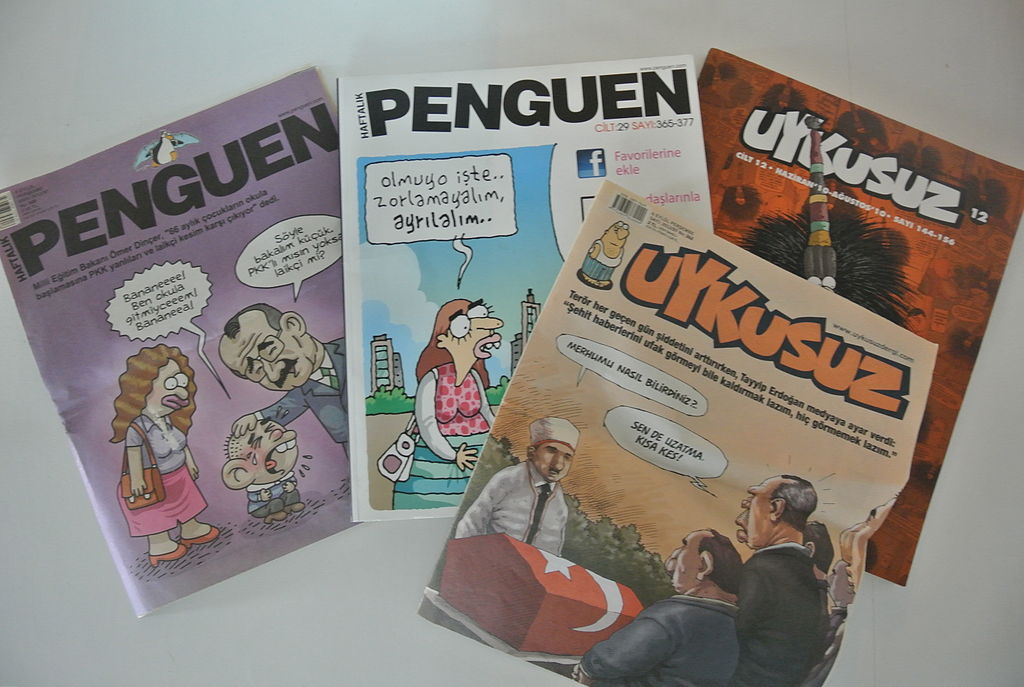

Turkish satircal magazines “Penguen” and “Uykusuz,” courtesy of Arved via Wikimedia Commons

We’ve been told not to use the metro. We’ve lived through warnings during Nevruz, the Kurdish New Year, to not go out due to potential clashes on the streets. The German Consulate and German schools in Istanbul shut down for two days ahead of the weekend due to a threat, and so the streets were nearly empty on Saturday, March 19th, when a bomb exploded on Istiklal Caddesi, the largest shopping street in the whole city, a place where any number of us living in the center of the city are wont to pass through often. This was a whole six days after the bombing in Ankara that killed 37 people at a bus stop on a Sunday evening.

The past few weeks have not been easy on any of us. Though Istanbul has reached a semblance of normal, friends and myself included have noticed that several of our favorite drinking spots, cafes, and eateries around Istiklal are empty in a way that they never are. Immediately after the Istanbul bombing and even now, there’s a perpetual heaviness to our interactions, an exhaustion tempered by a manic energy of feeling that it’s great to see each other alive.

Earlier last week the venerable satire magazine, Penguen, ran a cover that captured just that mood. A depressed-looking older man asks, “How are you?” to a younger, equally downturned man, who answers, “I’m fine, man, how are you?” At the very bottom of the grey-background, the older man replies, “Fantastic.”

That cover is us on the streets, at each other’s apartments, and in the bars. Our tense paranoia was brought to a temporary halt because the horrible thing that we’d been waiting for to happen had happened, but ensuing terror threats have done little to diminish our fears and the dark mood. From all sides, Turkey’s “zero problems with neighbors” policy has crumpled like a discarded wrapper on the sidewalk, and both domestic and international threats have turned İstanbullus more and more toward humor to keep themselves righted.

Satire magazines like Penguen, a number which also includes LeMan and Uykusuz, are a part of what’s keeping us sane. At first glance the lot of them look like they trade in stupid, lowbrow humor, which is far from the case. A great deal of the magazines’ cartoons make political or current events references -and then proceed to dance all over the initial concept -while the rest of the jokes play on cultural references only an insider would laugh at. That laughter, however, is precisely what we need right now.

While overt caricatures of President Erdoğan are absent in this issue, a photo of Riza Sarraf, being hauled off by a US agent for money laundering features in the inner page with the line, “Damn parallel states! Isn’t there anyone I can sleep with in this country?” Sarraf (also known as Reza Sarrab) is said to have close ties to Erdoğan, and thus by Turkish reasoning, any jab at him is simultaneously a jab at the president, which is cause for many readers of Penguen to laugh. Such satire is not new in Turkey, which has had political cartoonists since the late Ottoman period, and has had such celebrated satirists such as Aziz Nesin, but it is currently a surprise that magazines like Penguen manage to stay in print, despite court cases against them, and despite the recent government takeover of opposition paper, Zaman.

In times like these we desperately need a good laugh to not only survive but also to recognize the absurdity of the situations that one faces. Magazines like Penguen know this. In a cartoon by Solamz and Baruter in the very same issue, a man is being eaten by a giant spider, with riot police and observers ready to attack, but the man shouts, “Stop! Please don’t kill it! It’s a sin!”, which is only understood by the cultural reference to the attitude to not killing spiders in Turkey. Spiders are believed to bring good luck, and so even in the face of being eaten by a mutant spider, the man will not allow its death. This is of course on the extreme end of examples, but that is precisely what good satire does: Exaggerates situations so that we see the absurd in practices we don’t even question, and on the end of the absurd, turns the into a joke so that we can laugh at the folly of human beings.