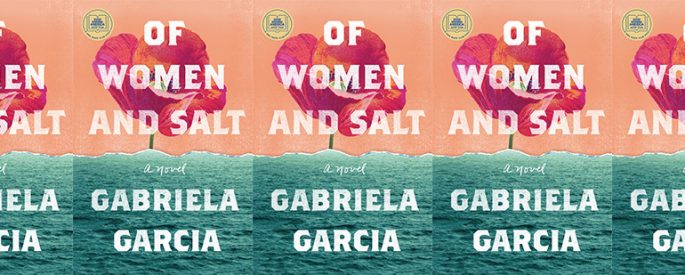

Storytelling and Inherited Trauma in Of Women and Salt

Early on in Gabriela Garcia’s novel Of Women and Salt, out earlier this year, one of the protagonists, Jeanette, a Cuban American born and raised in Miami after her mother, Carmen, leaves Cuba under mysterious circumstances, wonders “whether loss unspoken becomes an inherited trait.” A couple of years ago I wrote about inherited trauma in Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s We Cast a Shadow (2019); inherited trauma is the concept that trauma experienced by generations past can become embedded within their kin’s body. In We Cast a Shadow, the inherited trauma passed from the narrator to his son is a result of the structural racism he and his family and his peoples have experienced for generations. In Of Women and Salt, we see how daughters inherit the trauma experienced by their mothers and grandmothers, from the structural, such as political strife and exile, to the personal, such as losing a mother or father as a child.

Of Women and Salt follows generations of women in two separate families (the narrative spans over 150 years) who are dealing with exile and trauma. The stories aren’t told in chronological order—the order they occurred in time doesn’t matter. Throughout the novel, women are cut off from their kin, tragedy and death preventing connection and an open dialogue; while these conflicts are particular to individual women, they are also connected to the women who struggled before them.

Of Women and Salt opens with Jeanette, in the present, in a coma resulting from her substance use disorder; Carmen is praying over her in her hospital room, hoping for the chance to speak to her daughter again. The novel also follows Ana and Gloria, Jeanette and Carmen’s neighbors. Ana is a child, and early in the novel, she comes home to find her mother, Gloria, missing. Unbeknownst to Ana, her mother, an El Salvadoran immigrant, has been taken by ICE. The rest of the novel goes back and forth in time, back and forth between Miami, Mexico, and Cuba, showing the stories and histories of these characters to help inform the reader of their presents and to help inform how their stories all intersect.

As we read, we come to understand that because of the trauma generations past experienced, stories get silenced, whether because the people involved die prematurely or because they are so traumatized that they hope that by silencing their stories they can stop their own pain—or at least stop the pain from passing on to their daughters and granddaughters. But Jeanette seems to push back on this ideal—she goes to Cuba and while there tries to understand her mother, her mother’s pain, and her own pain more, thinking that the stories denied to her may hold part of the answer as to what trauma she has inherited, and therefore may have part of the remedy. This is something that her mother seems to connect with in the beginning of the novel: she pleads with Jeanette, saying, “tell me that you want to live. Listen, I have secrets too . . . Maybe there are forces neither of us examined. Maybe if I had a way of seeing all the past, all the paths, maybe I’d have some answer as to why: Why did our lives turn out this way?”

Inherited trauma is worse when you don’t even know what pains you’re inheriting. The fact that this novel is mostly set in Cuba and Miami only further brings this point home, for they are places that are so close to each other, but also so cut off from each other. They are places that are censored from each other, places where their governments erase their own peoples, places where stories are gone and nothing is remembered or known but pain and the loss of home. Without your parents being able to pass on their knowledge, it is hard to know the truth. And when parents are able to share their stories, they must feel confident that in doing so they’ll be causing less pain than what they already passed on, less pain than what their children already experience.

With inherited trauma, stories get buried—people cope by compartmentalizing, repressing, avoiding, and forgetting what has happened; the government erases the record of the trauma as well, gaslighting its own people as it insists that traumatic events didn’t happen, making them believe that they are just broken, with no cause to point at. Women are doubly quieted, doubly censored, doubly gaslit; that their stories are extra censored, and their inherited trauma even more so. In Of Women and Salt we see this in action when Carmen tells a comatose Jeanette, “There is so much I kept from you, and there are so many ways I made myself hard on purpose. I thought I needed to be hard enough for both of us. You were always crumbling. You were always eroding. I thought I needed to be force.” The inherited trauma in this family is worse because the women in the novel have internalized what their oppressors have done to them, and, in the hopes that they can stop passing on the pain to their daughters, have silenced their own stories.

The importance of passing on stories is shown early in the novel, when Maria Isabel, Carmen’s great-great-grandmother, reads and listens to lectornas, people who used to read newspapers and stories to the cigar rollers in Cuba. Of course, the colonial Spanish start to worry about the news articles being read to the workers, and begin to deny Maria Isabel the opportunity to read and listen to stories that sympathized with the revolutionaries. But before the stories were censored, Maria Isabel had “thought of escape, of recapture. She thought of herself. Of what it would be like if someone wrote a book about her. Someone like her wrote a book.” While Maria Isabel never gets the chance to write her own story, or see a book written about her, she does write “We are force” into a book, a sentiment she hopes to pass on to the next woman who picks it up.

Maria Isabel dies while birthing her daughter. For this family, the first structural trauma of the novel was the Spanish oppression of her and her peoples. But the first personal trauma was Maria Isabel’s death. And these traumas reverberate through every character to come. Maria Isabel knew the importance of stories, of listening and hearing and connecting and fighting, but her death denied the family this essential matriarchal lineage, increasing their pain.

Jeanette does not have the same understanding of the importance of stories that Maria Isabel had. For her generation, stories are looked down upon—they are nostalgia, waxing poetic, mentiritas about a place, a home, long gone. This feeling is also true for Jeanette’s mother, Carmen, who wonders why anyone “left a place only to reminisce, to carry its streets into every conversation, to see every moment through the eyes of some imagined loss, was beyond her. Miami existed as such a hollow receptacle of memory, a shadow city, full of people who needed a place to put their past into perspective. Not her. She lived in the present.” But the stories are the closest thing they have to answer the questions they have: What is hurting us? What is preventing us from going home?

Despite her perception, Jeanette is eager to learn her mother’s stories. She asks her for them throughout the novel so that she can understand her past, connect with the trauma of her mother, and maybe understand her own a bit more. But Carmen consistently shoots Jeanette down, so Jeanette decides to go to Cuba, to see her mother’s home and her grandmother and cousin, whom she has never met in person before. When she gets to the island, however, she thinks, “What am I doing here? I thought Cuba could be some kind of connective tissue, maybe even show me my mother. Make a piece of her make sense.” Jeanette is looking for something that she doesn’t completely understand; she is trying to help herself, cure herself. Exploring her mother’s homeland still results in her feeling broken, though, and she still falls into traps that she has lived in all her life—she catches herself thinking about stealing a book she finds in her grandmother’s home. It’s an heirloom worth countless dollars, but, sitting here with her grandmother, is open to the elements of Camaguey. Importantly, however, this experience is an echo of Carmen’s—earlier in the novel we learn that when she lived with her mother she “spent all her time in her room . . . And then I kind of feel it too, that maybe I was wrong to think there was something here for me, a recognizable piece of me.” Jeanette sat in the same room, trying to figure out how to escape with something from that house, from that Cuba, so she could bring it back to Miami, and she, too, wonders if there is anything left for her there in that house, in that Cuba.

The book does end on a cautiously optimistic note, in that the stories, even if never learned or told entirely to the other characters, are written down, are told and learned by the writer and readers, and can still be passed on. Echoing how the book Maria Isabel inscribed ends up with someone not blood-related to her, but still allowing us to hope her “We are force” marking provides some help, some relief, to the next woman who reads it, the text of, Of Women And Salt, can also do the same, depicting out these generational stories, showing these inherited traumas, and hopefully helping someone else to heal. Reading these stories, you hope the future daughters within Carmen and Jeanette’s extended family can start to reckon with the trauma they’ve inherited. Reading these stories, I hope that the people of my city, Miami, can start to experience this sort of reckoning themselves—can start to uncover all the stories burned and lost.

This piece was originally published on October 18, 2021.