Supreme’s Co-Optation of Barbara Kruger’s Oeuvre

I, you, he, me, she, they.

After working as a designer at Condé Nast Publications and at Mademoiselle, Aperture, and House and Garden as a photo editor, Barbara Kruger began creating collages that directly address the onlooker through the use of personal pronouns in the late 1970s. Through statement pieces such as Your Body is a Battleground and I Shop Therefore I Am, Kruger directly addresses her viewer while using “being” verbs (“I am,” “to be”, etc.) to encourage questioning within unexamined identities. Her use of personal pronouns is disorienting, inviting onlookers to think critically about the vast web of messages that stimulate production and consumption.

Kruger’s initial works, referred to as “paste-ups,” were created by pasting phrases directly over images drawn from commercial advertisements and then photographing the resulting collages. She juxtaposed cropped black-and-white photographs with phrases printed in Futura Bold, which appeared on black, white, or red text bars. The power of Kruger’s work lies in the pithy yet ambiguous nature of these phrases, as well as the layering of these words over found photography.

The phrases Kruger chooses allow her to question the unquestioned: she asks us to consider the ubiquity of visual advertisements by pairing her visuals with subversive and confrontational captions, redirecting the path of one’s eye from her images to her message. Kruger also chooses to break these messages up, fragmenting her words, so that one must journey with her across the image. When understood as both verbal and visual rhetoric, Kruger’s work confronts, disturbs, and addresses the reader.

Some have recognized the effectiveness of Kruger’s subversive messages and utilized her strategy and aesthetics for personal gain. Founded in 1994 by James Jebbia, the fashion brand Supreme, which was initially intended as a skateshop and clothing company, is now a “luxury skateswear” brand that is valued at $1 billion. Supreme’s skate decks and t-shirts are splashed with anti-establishment messages styled in a familiar format: a bright red rectangle surrounding a phrase presented in stark white Futura. The similarities are intentional—disliking the initial design options for his brand, Jebbia turned to a book on Barbara Kruger’s work for inspiration.

Others have detailed Kruger’s artistic and stylistic influences, including Agitprop, graphic design, photomontage, Russian Constructivism, conceptual art and poetry, so I will not attempt to argue where the line between inspiration and theft lies. Instead, consider the rhetorical effect of misrecognition upon Kruger’s conceptual art. If Supreme is recognized for Kruger’s iconic messages, is the brand co-opting and altering her words, thus changing Kruger’s rhetorical impact on an audience? What is the rhetorical purpose behind Kruger’s work?

In 2013, Supreme sued Leah McSweeny’s fashion company, Married to the Mob, for selling T-shirts that said “Supreme Bitch” for $10 million. When Complex asked her for a comment on the suit, Barbara Kruger responded via a blank email that included an attached Word document entitled “Fools.doc.” The text of the document read, “What a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers. I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce. I’m waiting for all of them to sue me for copyright infringement.” The confrontational words of Barbara Kruger’s email (as well as the circuitous route one must take to read it) directs the gaze of her reader in the same way she directs one’s gaze via her art. It is this confrontational power that Barbara Kruger draws upon in her earlier photography and graphic work.

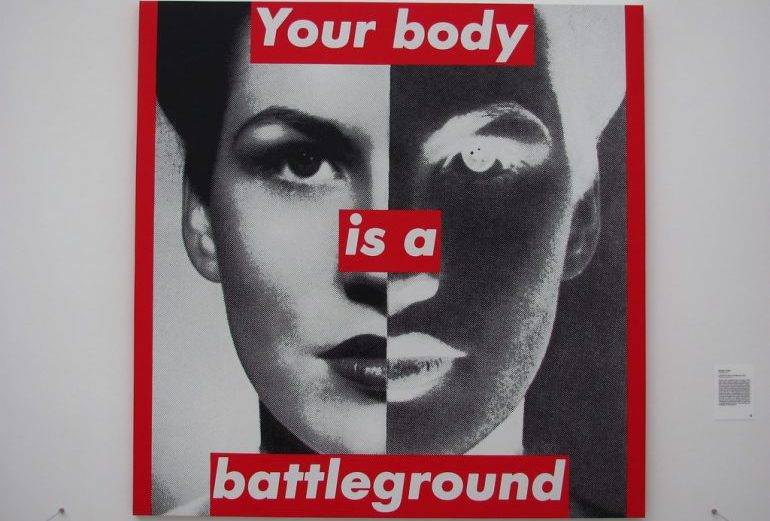

One of Kruger’s most published images is her 1989 piece Your Body Is A Battleground, which features a woman’s face split cleanly down the center. One side presents a black-and-white view of the woman’s face, while the left side reveals the photo negative of the image. The phrase “Your body is a battleground” is superimposed over the photograph, set in white Futura and surrounded by red rectangular banners. The phrase is split, fragmented so that the words “your body” run over the woman’s forehead, the words “is a” run across the woman’s nose, and the word “battleground” runs across the woman’s throat. The juxtaposition of the word “battleground” with the locus of the throat is perhaps intentional: it could be choking her.

Kruger created Your Body Is A Battleground for the 1989 Women’s March on Washington, where it took the form of a poster. She addresses the wide audience of this poster with the pronoun “you.” In one possible understanding of the phrase, “you” could be personal, addressing either the woman or one particular onlooker; or this “you” could be impersonal, addressing a group of people. While Kruger could have phrased her statement as a question (and indeed Kruger uses a variety of rhetorical questions throughout her body of work), she phrases this sentiment as a sentence, a declarative form which brooks no argument. This statement is not up for debate. Her intentional word placement, as well as the rhetorical formation of the phrase included in the work, renders rhetoric visible. Kruger draws upon the image of a battleground to invite her audience to consider how both the face of the woman in her collage is split apart and how the body of the politicized and curtailed.

In a 1991 interview with W.J.T. Mitchell, published in Critical Inquiry, Kruger says, “I live and speak through a body which is constructed by moments which are formed by the velocity of power and money. So I don’t see this division between what is commercial and what is not commercial. I see rather a broad, nonending flow of moments which are informed if not motored by exchange.” There is no division in this collage between commerce and the body, war and the body, danger and the body—the two are one and the same, linked together in the same way that we might read the personal and impersonal pronoun “you.” When paired with the phrase “Your Body Is a Battleground,” this collage speaks directly to the viewer of this image by calling attention to one’s invisible body. Through this image and phrase, Kruger invites contemplation of what it means for a body to become a battleground, a realm of contested power, marked by war. Kruger neatly pins ideas of commerce to the image by structuring this phrase through the beguiling form of an advertisement, which guides the reader’s eye down a sheet of ad copy, while structuring the body as a zone which interacts with power. When the body becomes a battleground, there is no neutral zone.

Kruger’s message is neither lightly stated nor lightly read, so it seems odd, at first glance, that the stylistic medium of her work would be referenced by Supreme. Given Kruger’s understanding of her own work, it seems important to ask: how does Supreme understand Kruger’s rhetorical impact? Do they share Kruger’s anti-establishment and anti-capitalist goals?

A famous untitled piece from 1987 has been co-opted by the brand. The original features a black-and-white print of a hand grasping a red box, overlaid with the words, “I shop, therefore I am.” This phrase is a reformulation of Descartes’ aphorism, “I think, therefore I am.” Supreme released a product they called the “Kruger Tee,” which featured white and black cotton t-shirts screen-printed with Kruger’s 1987 work; Supreme, however, retained only the image. “I shop, therefore I am” has been replaced with “Supreme.”

The phrase “I shop, therefore I am” presents shopping as a facility of existence. In order to be (“I am”) the subject of this sentence MUST shop. Therefore, it follows that without the capacity to shop, one does not exist. Kruger’s sentence critiques the rhetoric of ad copy, which entices the consumer to amass more and more goods in order to construct and bolster one’s cultural identity. Without the ability to shop within our current economic system, Kruger implies, we lack existence. Even if the onlooker does not look at Kruger’s statement and recognize the reference to Descartes, Kruger’s critique of commodification is still plain.

When Kruger’s words disappear from the image, however, the photographed hand no longer grasps Kruger’s statement. Instead of a critique of commodity fetishism, the image literally embraces amassing—and hoarding—material goods. Given that some of Supreme’s most outspoken fans own over fifty thousand dollars’ worth of brand merchandise, this is by no means a hypothetical suggestion. In addition, the abstraction of the image provides a sly nod to the onlooker—if you recognize the work as a Barbara Kruger reference, you are in-group, not out-group. You “get it.” Minus Kruger’s iconoclastic statement, the phrase loses its accessible message; Kruger’s art becomes just another product, placed within the frame of a cotton t-shirt which retailed for 68 dollars to be resold from anywhere between 500 and 700 dollars online.

While Kruger’s work “I shop, therefore I am,” deals with questions of identity and consumption, Supreme’s resell market exemplifies the brand’s draw with its superfans. Supreme’s subculture communicates via Facebook groups and subreddits alike to add to their collections, assembling objects which often become an important identifier of personality. Kruger’s work seems prophetic given this need to amass rare products.

The gendered nature of this consumption is also of note: while women who follow the brand definitely exist, its superfans tend to be mostly men, a fact that would be less remarkable if it weren’t for the community’s hostility towards fans that are women.

Founder James Jebbia discourages this resell market, yet his business practices tacitly encourage this underground economy. In 2009, Jebbia told Interview magazine “If we can sell 600, I make 400,” citing quality over quantity. Many women cite the line’s quality as their reason for wearing Supreme, as well as its sleek androgynous style (Supreme has no womenswear line and no plans to create one). While Supreme collaborated with Cindy Sherman in 2017 to bring two images from her Grotesque series to its skate decks, the majority of Supreme collaborations feature artists who are men. Supreme’s deliberate scarcity, its lack of collaborations with women artists, and its gendered underground economy all encourage uncritical consumption, the very thing which Kruger critiques in her work—and asks us to critique in turn.

Supreme’s work would not exist in its current form without Kruger’s legacy. Kruger shifted the way we gaze and think about advertising. Phrases such as “Your body is a battleground” and “Your gaze strikes the side of my face” speak directly to the viewer, offering messages that may disturb or invite further critical thought. Without Kruger’s words, Supreme’s products become the very thing that Kruger critiques, while failing to offer her any recognition.

This attempt to control and co-opt the work of women artists is nothing new. In 1971, Linda Nochlin asked us, tongue-in-cheek, “Why have there been no great women artists?” She concludes that the answer is systemic, not personal: women have been excluded from the category of “artist” on a structural level, excluded from apprenticeships within artists’ guilds, and excluded from the opportunity to pursue classical oil painting through traditional art classes. In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf presents us with the fictitious example of Shakespeare’s sister as a metaphor for the structural neglect of women artists. This metaphorical sister is never allowed to improve upon her talents in writing and acting, is forced into marriage, runs away, and dies in childbirth, buried in obscurity. Given the long history of women artists, the co-optation of their work and words for material gain should disturb us.

In 2017, Kruger staged her first piece of performance art, Untitled (The Drop), a pop-up shop that sold Kruger’s work on skate decks and T-shirts (all proceeds went to charity). Some of these red skate decks bore the word “JERK” in bold Futura lettering. Kruger’s use of a drop cleverly co-opts Supreme’s methods of commercial advertising and distribution. To quote Kruger’s email, “I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce.” Supreme is a case study that continually proves the prescience of Kruger’s statements. Kruger’s critiques of mass communication, advertising, and consumerism are proven again and again as Supreme continues to profit from Kruger’s legacy.