The Afterlife of History

On April 9, 2015, a larger-than-life statue of Cecil John Rhodes was removed from the main entrance of the University of Cape Town by order of the university’s leadership. Since 1934, the British imperialist had sat in a chair perched on top of a pedestal with his chin in his hand, perhaps pondering his legacy. The decision to remove the statue followed a month of protests by the group Rhodes Must Fall, who denounced the colonialist history that the statue affirmed. Only five Black South African professors were teaching at the University of Cape Town in 2015, and Rhodes Must Fall demanded symbolic and institutional change.

Such change does not come easily. Five years after the statue at the University of Cape Town was removed, Oriel College of Oxford University expressed its intentions to remove its own bust of Rhodes, who left the college a considerable donation in his will. But the college later announced that it had decided not to remove it, claiming “regulatory and financial challenges.” Instead, an explanatory plaque was installed next to the college’s statue that addresses Rhodes’s legacy. To many, the plaque is equivalent to a trial with no justice.

As the events spurred by Rhodes Must Fall and the debates over public images of slave owners in the United States make clear, a statue is more than the sum of its parts. But can destroying a statue atone for the oppression it symbolizes? What should replace the ones that are removed? How can art and literature imagine new histories and new ways of coming to terms with the past?

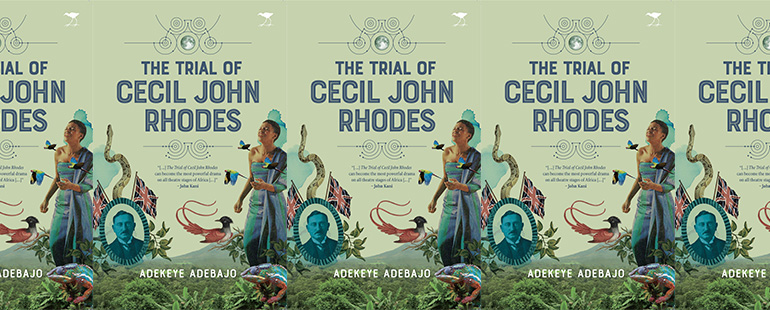

Adekeye Adebajo’s The Trial of Cecil John Rhodes, published in 2020, serves as a literary complement to ongoing confrontations with these statues. (The novella was published before Oriel College decided to keep Rhodes’s statue, and there are several places in the text where Adebajo references its imminent fall.) More than an iconoclastic takedown of Rhodes, the novella imagines a trial in which he is confronted with the extraordinary accomplishments of Africans and members of the African diaspora and is forced to answer for his brazenly imperialist ambitions. Rhodes ultimately gets the justice he deserves, but the novella also re-centers history on the African continent with encyclopedic organization and clarity. “It is therefore European imperialism as a whole that is on trial over the next two days,” states Judge Taslim Olawale Elias, the first African President of the International Court of Justice at The Hague, who presides over Rhodes’s imagined trial. Part of that imperialism is the suppression of African history. By taking Rhodes and his readers through a history of Africa and its diaspora, Adebajo interrogates Eurocentric history and what it chooses to suppress.

In 1990, Adebajo accepted a Rhodes Scholarship from Nigeria to study at Oxford University in England. “I felt that I should accept even the crumbs from the great imperialist’s gluttonous feast,” he writes in the acknowledgements of his book, “but promised myself that, having completed my studies, I would bite the hand that fed me by pursuing anti-imperial causes and eventually ‘trying’ the self-styled ‘Colossus’: Cecil John Rhodes.” Rhodes was the founder of the De Beers Mining Company and Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He profited off of South Africa’s mineral wealth and exploited Black Africans to process its riches. He wore his imperialism on his sleeve—Zambia and Zimbabwe were originally named Northern and Southern Rhodesia respectively. “I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit, the better for the human race,” he once declared.

Rhodes’s journey in Adebajo’s novella takes place over five days in an imagined African afterlife called After Africa, a kind of purgatory between Africa’s dark past and a speculative future. Ahmed Ben Bella, Algeria’s founding head of state, transports Rhodes across a river to this liminal land. After Africa can be understood as a compound noun, an imagined setting of the afterlife. But the term also suggests a time after Africa, an alternative future of the continent after its exploitation in the Herebefore. Adebajo provides the formidable cultural and political accomplishments of Africans and members of the African diaspora a time and place of transcendence.

Before his trial begins, Rhodes is guided through After Africa’s five heavens, where the Ghanian playwright Efua Sutherland introduces him to dignitaries from Africa and the African diaspora. In the first heaven, Rhodes meets the occupants of the Garden of the Ancestors. “Africa was the birthplace of humanity,” Sundiata, a fabled griot from Mali, informs Rhodes. “It is the site of the original Garden of Eden, which was located in East Africa near the Rift Valley.” Sundiata shows Rhodes artifacts from ancient civilizations and points out that ninety percent of the objects were looted by European colonizers. Rhodes marvels at objects from the Songhai and Oyo Empires and the Mapungubwe kingdom. “He had thought that Africa’s history began with the arrival of Europeans,” Adebajo writes.

Rhodes continues to the next four heavens: the Guild of Nobel Laureates, Dead Poets Society, The Celestial Music Concert, and the Afrolympics. He meets a pantheon of extraordinary figures: Ralph Bunche, Chief Albert Luthuli, Wangari Maathai, Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison, Chinua Achebe, Bob Marley, Tupac Shakur, John Akii-Bua, and Arthur Ashe, among many others. Before Sutherland leaves Rhodes to rest for the evening at the Hotel Afropurgatorio, she tells him of the sixth and seventh heavens in After Africa. The sixth heaven is where angels reside, “practicing their celestial hymns and plotting strategies for saving souls in the Herebefore.” The seventh heaven is the home of Africa’s most eminent ancestors, the permanent resting places of Yoruba and Egyptian deities. After Sutherland departs, Rhodes reflects on his unusual journey and returns “to his astonishment at the remarkable achievements of Africa and its diaspora.”

The Trial of Cecil John Rhodes is speculative fiction as historical revision. Adebajo imagines a world in which Martin Luther King, Jr. sits around a table with Anwar Sadat, Wangari Maathai, and Nelson Mandela. But After Africa is no more a fantasy than the white male heroism embodied in public statues and busts. The structure of Rhodes’s journey—from darkness and error to light and awareness—is familiar to European literature. It imitates Dante’s Divine Comedy, in which the author is led through various phases of the afterlife by his guides Virgil and Beatrice. Like Dante’s poem, Adebajo’s narrative presents justice as a judgement of heavenly ascendance or eternal damnation. But Adebajo does not dwell much on the hell that Rhodes first passes through to get to After Africa; he quickly witnesses the aftermath of the brutal violence of Uganda’s Idi Amin and the Rwandan genocide. Rather, Rhodes spends his time facing an alternative history, in which a foundational text of European literature is referenced to rework it as distinctly African in subject.

After their journey through After Africa, Sutherland leads Rhodes to the calabash-shaped stadium of the Afrolympics, where Rhodes is charged with five crimes in the Herebefore: “mass murder; racism; grand theft of Africa’s natural resources and land; exploitation and enslavement of African workers; and egotism and a vainglorious quest for immortality.” Rhodes gets a robust defense from his Counsel for Salvation, Nelson Mandela and Harry Oppenheimer. Mandela speaks of Rhodes’s noteworthy philanthropic contributions to education and the accomplishments of the Mandela Rhodes Foundation, although Adebajo does not imagine Mandela as fully comfortable in this position. He pauses for sips of water and gauges the reaction of the trial’s crowd. Mandela’s defense suggests that colonial power cannot be so easily untangled from the identities of those who are oppressed. The defense of Harry Oppenheimer, whose imperialist endeavors closely paralleled those of Rhodes, takes a more patronizing tone. “This was a man ahead of his times,” he claims, “who should be praised, not punished, for opening up Africa to Western infrastructure and industry.” The crowd of After Africans gathered for the trial grows increasingly impatient, yet Adebajo presents a balanced picture of Rhodes’s involvement in African history and makes his eventual damnation appear more just.

The trial concludes and Judge Elias reads Rhodes his punishment. His remains from the Herebefore are to be removed from Matopos Hill in Zimbabwe and transported to England. His assets will be confiscated and used as reparations to compensate the descendants of his victims. And last but not least, he is sentenced to eternal damnation. Judge Elias politely thanks Rhodes for his cooperation and the crowd “agrees that they had just witnessed the trial for all ages in After Africa.”

The trial topples Rhodes’s privileged place in history, yet Adebajo does not attempt to anoint a single Black African hero or heroine in his place. The extraordinary figures who Rhodes met in After Africa are present on judgement day, and they stand with the crowds gathered in the stadium to witness the historic event. In this way, Adebajo presents After Africa as a post-heroic world, in which those who contribute to the history of Africa and its diaspora are celebrated but not idealized above flaw and reproach. Adebajo explores Mandela’s human complexity most deeply. During the final judgement, Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba admonishes Mandela for associating himself with Rhodes. “Mr. Mandela has surely taken the African concept of ubuntu too far in rehabilitating an evil figure,” Lumumba declares. Lumumba’s words are a reminder of the contradictions of even the most heroic humans. They suggest that the problem does not entirely lie with who we heroize, but the act of heroization itself.

In December 2019, Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War was unveiled outside the Virginia Museum of Arts in Richmond. A young Black man wearing a hoodie, ripped jeans, and Nike high-tops confidently sits astride a galloping horse. Larger than life, the bronze sculpture sits on a stone pedestal. Wiley asks everyday people of color to model for his paintings and sculptures, thereby depicting anonymous youth who would be most vulnerable to historical erasure. In this way, Wiley shuns heroes, suggesting that everyday people should feel part of history. A few blocks away from the museum, statues of Confederate leaders loomed and glorified a history of white supremacy on nearby Monument Avenue. Wiley’s young Black man provided a much-needed interrogation of this stretch of Lost Cause iconography. The last Confederate statue, depicting General Robert E. Lee, was removed in September 2021. Like The Trial of Cecil John Rhodes, Wiley’s statue addresses the past at the same time it strives to overcome it. Both use the language of memorialization to depict and honor those who have been oppressed. Adebajo and Wiley replace the white-washed narratives of the past, but they do not forget the oppressors. They demonstrate the capacity of art and literature to hold together conflicting histories and imagine, or maybe even anticipate, alternative futures.