The Black Aesthetic: Musical Revolution in Childish Gambino’s Awaken, My Love!

In times of social turmoil, African American poets disseminate messages demanding change. Great writers such as Amiri Baraka and Nikki Giovanni wrote of freedom and the rhetoric of the Black Aesthetic. When poetry is set to music, harmonious beats relay liberating feelings that transcend history and culture. The Black Aesthetic is often universally pleasing, but beneath the verses documenting aspiration, empowerment, and fear is a call for cultural revolution. Posts for this series can be found here.

Lay back as you listen to Awaken, My Love! by Childish Gambino, and thoughts of social turmoil will disturb your rest. Amid his poetic verses are allusions to metaphorical monsters that call to mind police violence, marches, and riots. If you consider poetic tropes and archetypes from African American culture as you think about the intentions behind the album’s verses, you’ll see that the traditions of black liberation and the lyrical protesting of the dehumanization of blackness resonates. “Boogieman” and “Riot” in particular paint images of black people who, in the eyes of those who wish to dismiss their humanity, are metaphorical monsters.

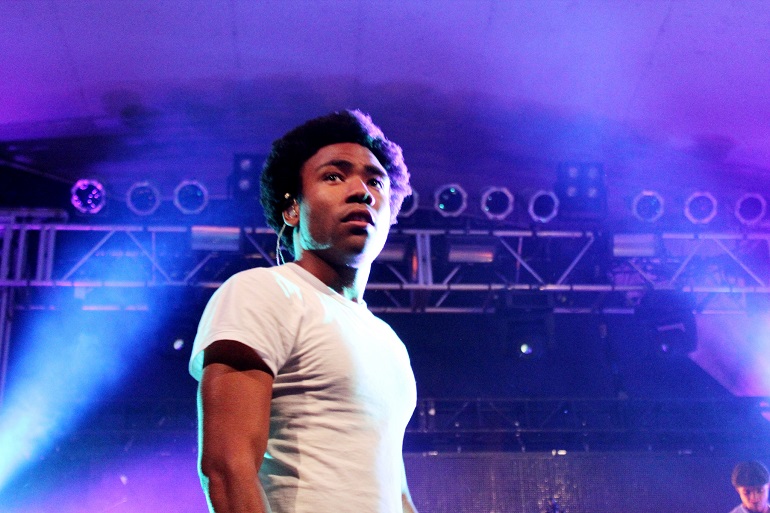

As Donald Glover was writing Awaken, My Love!, he had a global revolution on his mind. Parallels between the 1970s and recent social uprisings made Parliament’s Funkadelic album resonate with him: “There’s something about that ’70s black music that felt like they were trying to start a revolution.” The power of music had him seriously considering how society overturns systems. As a result, when Awaken, My Love! incorporates lyrical spin on the productions of Childish Gambino’s African American musical forebears, homage to the collective black liberation movement is paid.

If you point a gun at my rising sun

Though we’re not the one

But in the bounds of your mind

We have done the crime—”Boogieman”

As I listen to Glover’s words with a resistance writer’s mindset, I hear a man imploring police not to falsely judge him. With the rash killings of unarmed black men by officers sworn to protect and serve, the meaning of innocence weighs heavy on many Americans’ minds. Why is white innocence and black innocence not valued equally in our American democracy? In “Boogieman,” Glover makes clear that in the mind of some authority figures, black skin makes an African American a perpetrator, a presumed criminal. For that reason, Childish Gambino’s blackness is a metaphorical boogieman, an American monster that is perceived as a sinister force, a grave threat ready to attack. Glover confronts the questions of black liberation: “But if he’s scared of me/ How can we be free? Yeah”. Irony resonates. The one who wields the power of the state acts as the threatened arbiter of (in)justice.

Now more than ever, frustration over injustice is spilling marches into the street. America watched last year as well-meaning protests of police violence led to social unrest. However, the perceptions of white protests versus black protests differ. Black Lives Matter marches and rallies are viewed as unpatriotic and a threat to our American democracy. Meanwhile, protests by whites are perceived as peaceful and a positive expression of civil liberties. Like in the song “Boogieman,” black people are perceived as inherently dangerous. “Riot” is an amazing follow-up to the thematic idea that black skin is a boogieman that may eventually lead to violence. The pulse of the country is mirrored in the song’s desire to put a human face on the metaphorical monster.

It’s a rapid-paced track consumed with melodic howls. I usually blare this song, composed of screams over the sounds of a synthesizer, about social upheaval. The word “fly” is repeated three times before the word “son”. Figuratively speaking, there’s an element of a soothsayer bestowing advice or warning society about the urgency of the societal dissatisfaction that often incites social uprisings.

No good’s happening

World, we’re out of captains

Everyone just wants a better life

They tried to kill us

Love to say they feel us

But they wont take my pride—”Riot”

When he says “No good’s happening,” think of recent years in Ferguson, Baltimore, and Charlotte. Those protests and the resulting social unrest were largely caused by cultural concerns over police violence in African American communities. Unlike the Civil Rights Movement era, now there’s no clear leader or defined leadership. There’s a sense of expiration. Where did the leaders go? Tragically, I’m reminded of the martyrdom of Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, and Fred Hampton.

Our beloved African American leaders are dead and gone. Childish Gambino’s Awaken, My Love! implores our compassion. People are acting out of desperation. Frustration resonates with each lyrical verse. Contrary to majority opinion, African Americans who riot want a better life. Many are frustrated because they’re treated like second-class citizens. Although many Americans may view rioting as counterproductive, rioters are not bad people; they’re not monsters.

Metaphorically speaking, “they” refers to the systems of slavery and mass incarceration that dehumanize a culture. The collective history of slavery and mass incarceration are considered forms of cultural genocide. The word “tried” in “Riot” probably implies the system didn’t succeed at erasing black culture or black people. After everything African Americans have gone through in this country, there remains a desire for peace. But the desire for African American liberation can’t be extinguished. “Boogieman” and “Riot” challenge listeners to transform their perception of the metaphorical black monster of the American imagination. This cultural revolution will be a war of ideas, deconstruction of stereotypes, and a reconstruction of institutions that obstruct black liberation. Whatever the case, the system won’t take our pride, creativity, or the assertion of our humanity.