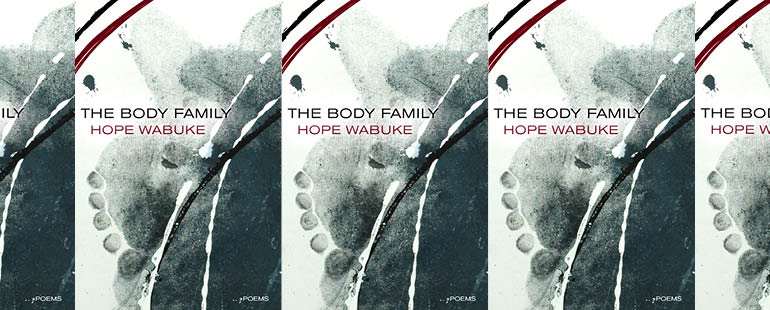

The Body Family’s Sharp and Intimate Portrayal of Trauma

The Body Family

Hope Wabuke

Haymarket Books | April 12, 2022

The Body Family, Hope Wabuke’s first full-length collection of poems, is one of those debut volumes, like Wallace Stevens’s Harmonium or Marianne Moore’s Observations, from which a reader gets the sense of a voice and a vision long in development and mature on arrival. It reflects her family’s experience as refugees from Idi Amin’s Uganda and its terrors, and reflects their landing in the United States, a supposedly safe harbor with terrors of its own for anyone of African descent. It also reflects her complex, mobile relationship with her father and a no less complex, mobile relationship with her young son. Glancingly, in flashes, it reflects a relationship with an abusive partner. Any one of these bodies of experience could have been matter sufficient for a volume, and to include them all risks capsizing the boat, but Wabuke’s voice, pared down and deliberate even when passionate, keeps the ship afloat and on course.

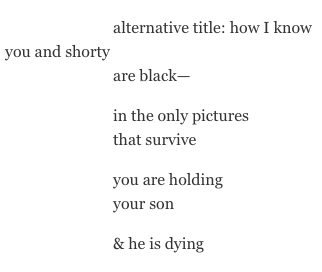

The titles of individual poems indicate some of the ways Wabuke manages her heterogeneous and volatile material. Many poems are named for parts of the body (e.g., “Stomach,” “Ears,” “Leg,” “Tongue,” “Skin”), and many bear titles reminiscent of an art exhibition’s catalog (“Figure 12: Self-Portrait as Fire and Oshun. Materials: Water”). The names of books and figures from the Bible are a prominent motif. Wabuke adopts this device advisedly, acknowledging in a prefatory note the Bible’s long involvement in rationalizations for colonization, marginalization, and enslavement, but it serves her purposes admirably. A prose poem channeling her father’s complaints of his children’s ingratitude at being delivered from Uganda and his bafflement at their wish to return there is wittily titled “Judges” after the book of the Bible that recounts the Israelites’ woes upon arrival in the Promised Land. Idi Amin is David in one poem, a young hero confronting the British, Goliath in the next, terrorizing his own people. Ruth and Naomi, who found ways to endure through exile, bondage, and male folly, appear frequently. Wabuke’s conjunctions of Biblical archetype and contemporary actuality are always intriguing, sometime powerful, as in the invocation of Mary in “Figure 3: La Piéta. Materials: Breath and Air”:

Each of the book’s four sections has a center. In Part I, the experiences remembered are mainly not Wabuke’s but her parents’: their dangerous exit from Uganda and arrival in a new country where “the rocks our American neighbors hurl / through our windows just miss / breaking the small bones of my sisters’ bodies” and the children have no language in common with their grandmother. “Refugee Mind” speaks of the challenges of the parents, who thought “the leaving // would be like the banyan tree / rising to spread wide / branches turned down become / root again grow new life,” but find it hard work to “connect deep & strong / within alien ground.” That work must be done, though, “for there are always storms coming.”

The storms arrive in Parts II and III. The father dominates, a figure of strength and fragility, certainty and doubt, who loves and protects but also hectors and demands. Ruptures occur that the birth of the poet’s own son, in whom she can see what her father might have been as a boy, perhaps can heal:

Agonizingly, one thing the grandfather and grandson share, as black males in the United States, is the traffic stop, the armed neighbor, the choke hold. Four poems titled “Breath” recall those whose plea, “I can’t breathe,” was ignored.

and I just want you

my father to protect

me teach me how to protect my son

myself because they have put in a law

that says the last man standing can say

I felt threatened and shoot

to kill and then walk free

The many strong, startling poems in the first three sections of the book—besides those already quoted, I also ought to mention “Stomach” and “First and Second Crowns: A Reverse Pantoum for Two Voices”—did not prepare me for the impact of the longer poems of Part IV, in which the experience of childbirth is braided with the personal and collective histories presented earlier. “Figure 11: Portrait of Black Jesus as the Dying Father, Risen Mother & Watching Daughter. Materials: Water & Memory” is a prayer or a conjuration or a summoning with eerie incantatory power:

“Pieta IV: A Wanting Red Thing Is a Hungry Ghost” puts us at the center of giving birth to a new being in a merciless world, “this / most ancient terrible thing,” and finds hope in the sheer power of the continuity of the body and the family:

The Body Family bears two dedications, one at the beginning of the volume, to Wabuke’s parents, and one at the end, to “those disappeared from the violence of genocide and war.” The double tribute seems appropriate and may be the best explanation of what the “body family” is: both one’s personal ancestral tree and wider historical collectivity to which one belongs.

Parul Sehgal’s recent complaint about the “trauma plot” in contemporary fiction—that it “flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom, and, in turn, instructs and insists upon its moral authority”— resonated with many readers of contemporary fiction, and with trauma occupying ever more ground in the landscape of the American lyric, many readers of contemporary poetry might have their own concerns about flattening, distortion, and reduction. The Body Family can stand as a counterexample, however. Here we have trauma in its contradictory particularity, its incalculable aleatory combinations—not flattened or reduced at all, but sharp, salient, and intimate.