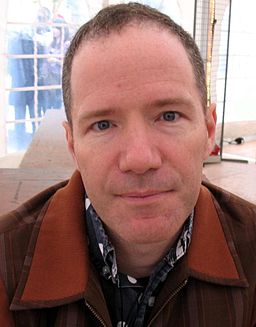

The Books We Teach #8: Interview with Rick Moody

Rick Moody is author of the novels The Four Fingers of Death, The Ice Storm, Purple America, The Diviner, and Garden State, which won the Pushcart Press Editors’ Book Award. He is also the author of two collections of stories, The Ring of Brightest Angels Around Heaven and Demonology, as well as a memoir, The Black Veil, winner of the PEN/Martha Albrand Award, and a volume of essays, On Celestial Music. He has received the Addison Metcalf Award, the Paris Review’s Aga Khan Prize, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. His short fiction and journalism have been anthologized in Best American Stories 2001, Best American Essays 2004, Year’s Best Science Fiction #9, and the Pushcart Prize anthology. He has taught at the State University of New York at Purchase, the Bennington College Writing Seminars, the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the New York Writers Institute, and the New School for Social Research. He now teaches creative writing at New York University, Skidmore College, the School of Art at Yale University, and the Atlantic Center for the Arts.

Here, Rick and I discuss the mentorship class model, his reputation for assigning works that students dislike, his push to rethink pedagogical preconceptions, and students singing (yes, singing) during creative writing classes.

Tell me about the classes you’re teaching at NYU this term.

There are two courses this semester. One is what they call in these parts a “craft class.” (I personally have always thought this was a misnomer, but what do I know?) It’s entitled “The Other Europe,” and it consists mainly of Eastern and Central European fiction (with some Germans), and is organized around the proposition that this topographical portion of Europe has its own tradition, much at odds with what I might call the Anglo-American or Anglo-Gallic-American axis. We started at the beginning of the semester with the Brothers Grimm, and are going to end with Ryszard Kapuscinski and Magdalena Tulli. Or maybe [Karl Ove] Knausgaard (not sure which yet).

The other class I’m teaching now is in the NYU art department (where I have taught for a couple of years, as I also do at the School of Art at Yale University), and it is sort of a “Special Topics in Appropriation” class. The art school classes I have taught (which are graduate level, like the lit class) are cross-genre classes for people who are mainly expert in photography/video/painting/sculpture, etc. And they take as their pre-supposition the idea that creativity knows no genre, and that anyone can write if they are made free to write. Unencumbered. Empowered.

It happens, this semester, that I am using a lot of exercises from the Charles Bernstein/Kenny Goldsmith playbook of found text and collage. In order to desensitize the artists in the areas of shame and self-consciousness. I have to say: these art school classes have been sort of my own design, and they are extremely challenging (often there are people in them who don’t write or don’t even necessarily have college level English skills), and also remarkably rewarding and thrilling. My first NYU art department class in 2012 was the single most thrilling class I’ve ever taught.

What kind of workshop style do you tend toward? What kind of dynamic do you like to establish early on? (I think back—fondly—on a piece you wrote for The Atlantic a few years back: “We need to be alert in the workshop setting to the problems inherent in the very structure of the workshop.” A great piece of advice, I think.)

I don’t think I teach a conventional workshop at all and I sort of hate the word workshop. As you can see, right now I’m not teaching a traditional creative workshop, and in fact the only conventional workshop I teach annually is at the summer program at Skidmore College (where I have taught some ten or twelve years). There it lasts exactly two weeks, because that is all I can take of the workshop as conventionally constructed. I think the workshop is a corporate structure, borrowed from the corporate world, and perhaps perfected in the cauldron of the 1970s actualization movement, and as such I don’t think it’s particularly good for teaching writing, at least not the kind I like. The kind of writing I like tends to resemble nothing that ever happened on earth before, and that work is very difficult to talk about in workshop settings, because we can’t subject it to the same tired bits of advice (Change it to the third person! Start here! Maybe you need the present tense!), that we have so overused before.

My model, such as it is, is a mentorship model, which is to say that I care personally, and I involve myself personally/emotionally with the work of each student, and I try to make it such that they want to reach for more, do better, risk more, try new things, abandon limited objectives, individuate, and so on. For me it is personal, to the best of my ability, and it is about making more of the writer and of the writer’s task in each case. I also think it’s possible to do this, to teach in this way, in a classroom free of rancor and backbiting and competitive jostling. So: my class should be a place of peace, a place where anything is possible, where the code of realism is in disrepute, and the worst thing you can say, the absolutely verboten thing, is the phrase: The New Yorker.

What draws you to a text, pedagogically speaking? Do any works come to mind that are as enjoyable to teach as they are to read?

I like to be surprised.

A list of things I have taught recently that went really well and which moved me a lot, in no particular order:

Don Quixote, Icelandic Sagas, the Scheherazade, Rabelais, The Golden Ass, C. G. Jung, Lenz (by Buchner), Bruno Schulz, Gogol’s stories, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, The Rings of Saturn (Sebald), Transcript (Heimrad Backer), Pale Fire (Nabokov), and so on.

Can you recall a unit of which you’re particularly fond?

Last semester I taught “Narrative Art to the Age of Cervantes,” with the idea that the pre-Cervantes idea of storytelling was freer and more unpredictable, and some of the books from the above list are cribbed from that manger. It was a pretty exciting class for me. I hope for the students as well.

Is there something quite new that you are teaching this term or thinking of teaching next term?

I’m teaching a class at Atlantic Center for the Arts in the winter which is going to be across genre, very widely construed. I have specifically invited musicians to take part, as well as writers and visual artists. It’s going to be a big experiment in creativity. Lots of writing, but lots of other stuff too. Once this semester I made my creative writing students sing in class, and it was a moment of great accomplishment and breakthrough, it seems to me. They instantly became sweeter, more talkative, and more generous to one another, and I am still seeing the ramifications of it. I am going to try to build an entire class on this principle. The principle that there is no genre.

What is some advice that you often give to fledgling creative writers?

It’s more about the rewriting than the writing.

Could you talk to me about one text that elicited a wholly (or mostly) positive response from your students? What about this work caused such collective enthusiasm, do you think?

Part of the interest for me, is in the fact that there is almost never unanimous assent, and I use that to my advantage. I think in some ways I am well known for assigning work that some people hate. For example, this semester I taught a two-week stretch of Witold Gombrowicz and Robert Walser that attracted a fair amount of discontent. I was actually disappointed by the Walser class, because I thought they were reading like plumbers or electricians, not like writing students. They were like little Halloween brats who had their precious candy corn taken away from them. (There’s not really a story here! And no characters either! How am I supposed to read this?)

I mean to remind them of this at the end of the semester. If one reads only in one’s comfort zone (despite what Borges said on the subject), then one is never challenged. Reading is not about reinforcing the code. It’s about going on an adventure. I could assign stories from the canon of American naturalism all semester and reward student preconceptions about these things, and then all the students would do what writing programs seem to want them to do—but I would have to be lobotomized at the end of the semester. So I try to challenge them. And that results in some grumbling when they don’t accept the challenge.

That said, it seems to me everyone loved the Scheherazade last semester, because what’s not to love: djinns, magic lanterns, stories within stories, beautiful maidens who are about to have their heads cut off, and so on. That one was a universal a crowd pleaser. And it’s infrequently taught in creative writing.

Does teaching play a big role in your own writing? How does your life as a teacher play into your life as a writer and vice versa? Are your personal projects completely disparate from your teaching life, or do your books and classrooms bleed into each other?

My books have nothing to do with the classroom at the level of content. I suppose I’d like to keep it that way. Or that’s how I’m thinking about it today. I dislike many novels of the academy. That said, I think teaching is creative. Or, at least, I make it creative for myself by staying off balance, by challenging myself in the classroom, by teaching books I don’t know well and want to know more about, by giving a lot of assignments, by asking people to risk a lot, as I myself risk a lot. By blurring distinctions between genres, by blurring distinctions between the workshop and the literature class, by trying to rethink preconceptions wherever they come up.

The result of all this is that sometimes teaching is as rewarding as writing, especially in the personal sense. The emotions being transmitted through the classroom, along that electrical circuit of literary community, are just as complex as those being transmitted from writer to reader. Which means that I have depleted some of the creative capital I have available to my work. That’s the basis on which the two are related: they now come from the same place.

It’s also worth saying, however, that the students sometimes buoy you up, and keep you going when you are not certain why you are doing it anymore—their youth, their energy, their enthusiasms (for good or ill). Sometimes the feedback loop is such that one leaves the classroom more excited than when one stepped in. So there’s that as well. Sometimes the professor is the student.