The Burden of Witness: The Sandcastle Girls, #MeToo, and The Armenian Genocide

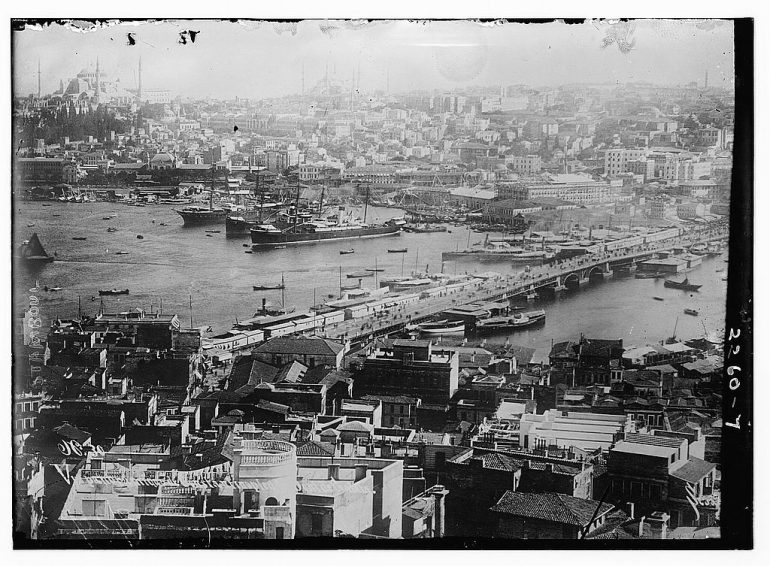

On April 24, 2015 I was in Istanbul when the hundred-year commemorations of the start of the Armenian Genocide were taking place. There, at the mouth of İstiklal Caddesi, the largest shopping street in the city, a group of Armenians, Turks, and foreigners ended a walk to remember the massacre. They held red carnations, photos of the intellectuals, and signs—in Turkish, Armenian, and English—stating their desire to remember the Armenian Genocide.

On April 24, 2015 I was in Istanbul when the hundred-year commemorations of the start of the Armenian Genocide were taking place. There, at the mouth of İstiklal Caddesi, the largest shopping street in the city, a group of Armenians, Turks, and foreigners ended a walk to remember the massacre. They held red carnations, photos of the intellectuals, and signs—in Turkish, Armenian, and English—stating their desire to remember the Armenian Genocide.

I never thought I’d see such a thing, and it gave me hope. The Turkish government has long maintained its decision to refer to the Armenian Genocide of 1915 as a massacre, indicating the country’s vehement refusal to submit to international pressure from 28 countries that have recognized the Genocide to take responsibility for the crimes of the Ottoman Government. Turkey continues to pressure countries like Germany when they come close to passing resolutions of recognition or countries like the US to verbally recognize the Genocide on its acknowledged commemoration day, April 24th, which is fraught when those countries are dependent on access to the NATO airbase at İncirlik and working with the Turkish military in the ongoing war in Syria. The walk in 2015, then, seemed like a movement from within to embrace and acknowledge the country’s past in all of its glories and horrors.

What we generally know about the Armenian Genocide is that the Ottoman Army and bands of irregular troops killed an estimated 1.5 million Armenians from 1915 to 1923, either by outright murder or through forced deportations into the Syrian desert. The official Turkish narrative about the Genocide however, is that it was a time of war in which everyone in what remained of the Ottoman Empire, including Turks, Armenians, Greeks, and Kurds, were killing each other, so for national security reasons, the Armenians, who the Ottoman government claimed were colluding with the Russians, had to be killed. The civilians, they say, were moved for their own safety, and because there weren’t enough supplies for them or their military guards, many died while being relocated.

Like most Greek-Americans, I’d spent six years in Greek School in the US, where I’d been fed a serving of Greek Nationalism with every noun declension–of which there are many due to how irregular Modern Greek is as a language. I’d been taught that Asia Minor and the former lands were our birthright, the basic details of the War of Independence from the Turks, and that “It was better to have one hour of freedom than 40 years of slavery and imprisonment,” from one of the many nationalistic poems we had to memorize, written in a version of Greek none of us, not even our audience, understood. I never learned about the Hittites or the Persians, or even the Armenians, Jews, and Kurds also living in Asia Minor. Greek School as was all Greek, all the time, with no mention of any overlapping histories.

As a result, what I thought when I heard the word “Armenian” was the Armenian Genocide. When I first moved to Turkey a few years ago, the hushed tones anyone used when talking about the ethnic and religious minorities living in Turkey–Kurds, Armenians, and Greeks included—never encouraged me to explore the use of the word “genocide” in the country. The Turkish government’s denial on an international level was enough to dissuade me to do no more than wonder what had actually happened in 1915. Those who were critical of the government’s denial of the Genocide like Orhan Pamuk and the journalist, Hrant Dink, had been charged with insulting Turkishness, facing three years in jail, or, in the case of Dink, murdered. Even though I questioned the narrative I had been fed in Greek School, I knew from how little the 1955 Pogrom in Istanbul, which had pushed out my own family from Turkey, had been discussed that talking about such things was not a matter of everyday conversation.

After I returned to the US, I embarked on a research trip at the Library of Congress to dive into newspaper archives of the Turkish paper, Cumhuriyet (Republic), for a historical novel I’ve been working on about Greeks in Istanbul in the 1950s. While I was waiting for my microfiche reels to arrive, a librarian at the African and Middle Eastern Reading Room mentioned in conversation that he thought Chris Bohajalian’s novel The Sandcastle Girls should have been made into a film instead of The Promise, a film set in the late Ottoman Empire about the Genocide that was based on a previously unproduced screenplay called Anatolia, and I was brought back to the world I’d left behind.

The Sandcastle Girls tells the story of an American nurse volunteering with the Friends of Armenia in Aleppo in 1915 who falls in love with an Armenian engineer as well as that of her granddaughter, who, in New York in 2015, traces her family’s history through an old photograph. The touching novel humanizes the time in a way that the very best fiction does: It depicts the curious way that family and group memory forms through the selective telling of stories. It shows the drive people have to uncover personal history when it has been buried.

This novel is hardly the only work of fiction set during the Armenian Genocide. There are several lists of other novels and books that deal with the topic. Notable are Peter Balakian’s lauded work of nonfiction The Burning Tigris, and his memoir Black Dog of Fate. There are works by Turkish scholars who acknowledge the Genocide, like that of Taner Akçam, who in 2005 took part in a groundbreaking conference in Istanbul on the Armenian Genocide, despite Turkish government officials’ attempts to pressure organizers into canceling the event.

Though that conference was a significant step forward in discussing the truth of the Armenian Genocide, The Sandcastle Girls makes clear that it’s always the victim who bears the burden of witness, especially when restitution or acknowledgement is absent. This is clear in the #MeToo campaign, which arose in the aftermath of the publication of articles discussing sexual assault many allege was committed by Harvey Weinstein. Like survivors of sexual violence coming forward with allegations, survivors and descendants of the survivors of the Armenian Genocide bear the burden of educating the public. That burden seems to be the defining factor of the Armenian Diaspora.

Shortly before I moved to Turkey in 2009, I dated an Armenian-American guy. He was the first member of the Armenian Diaspora I had ever met, and didn’t share information on his ancestry aside from the time he had pulled out a loaf of choreg, the sweet, mahlepi-flavored bread known in Greek as tsouréki. Choreg, to me, became a symbol of what it meant to be Armenian.

He knew I was going to Turkey, and one day decided to lecture me on ”Greater Armenia,” an area that spanned from present-day Muş to Erzurum, Erzincan and Van in Turkey, to the country of Armenia itself. It was the single instance he’d decided to mansplain to me, and I was having none of it.

“Greeks were in this area for centuries, too,” I had said at the time.

I had known that the region had a rich history and that the Turks were not the first rulers or inhabitants of the land that now belongs to Turkey. We’d never discussed the history of Asia Minor before, but it really revealed how little he knew me when he assumed that I had no interest in history. I wondered if this attempt at a lecture was his way of expressing his discomfort with my move or of asserting his own history on me. But then if you feel as if no one knows about your group of people, there are times when you will lecture perhaps because you’re screaming inside that no one knows and that they should know about a nation that now exists in replanted communities.

I could say that there’s so much to embrace through one’s culture, and that one should refuse to be solely defined by surviving annihilation and trauma. But I won’t and can’t say that’s the answer. The truth of it is, perpetrators won’t acknowledge what they’ve done until the victim takes the risk of reliving the trauma, being disbelieved, and possibly even feeling shame for being violated, for speaking up. And that’s not easy. It’s not easy on a single person, nor is it on a whole group of people. The Armenian Diaspora has been bearing witness to what their grandparents and great-grandparents survived for decades, and there’s no way to shift away from that until radical changes take place in Turkey from within the country itself. No amount of pressure on the Turkish government from foreign powers will do that.

When I think back on the commemorative walk in Istanbul, it feels as if it happened a decade ago. Since 2015, the war in Syria has escalated, the war against the PKK has been renewed, the government survived a 2016 coup attempt, and many MPs from the only non-nationalist, liberal and pro-Kurdish party, including its co-leaders, have been jailed. But I still think back on that rally with hope. Though burden of witness is yet again placed on the Genocide victim’s descendants, The Sandcastle Girls reminds us that to be alive is to engage in a work of memory.