The Physical and the Emotional in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things

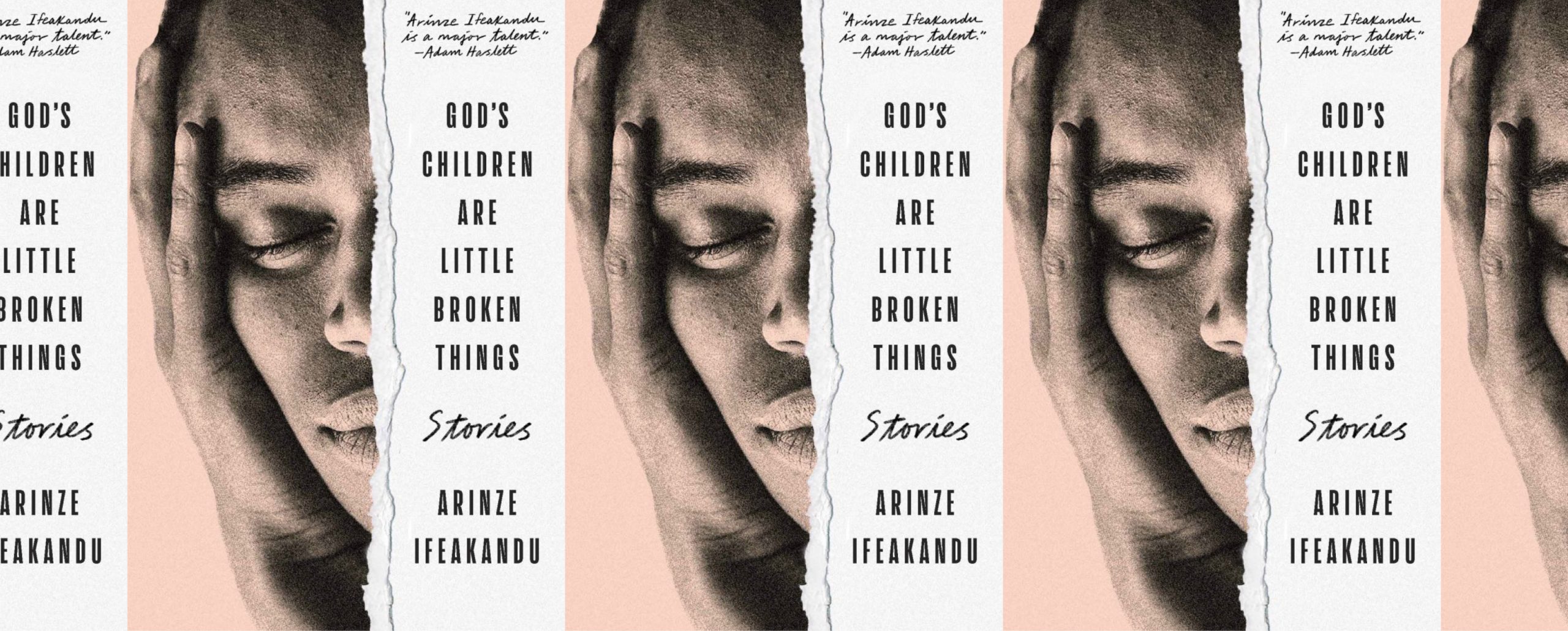

In God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, Arinze Ifeakandu’s beautiful debut collection out tomorrow from A Public Space Books, people often struggle to express their true emotions and feelings. Living in a world that may not accept who they are and whom they love, it is at times difficult for the book’s queer characters to speak what’s on their mind. Ifeakandu (who will have a new story published in the Summer 2022 issue of Ploughshares, guest-edited by Jamel Brinkley and out in July) often uses a description of the world to express their emotional state—at times he uses metaphor; at others, he simply describes the landscape. The way that he chooses to depict a character’s world, seen through their eyes, also reflects their emotional landscape. It is a subtle and beautiful way to portray these characters, to allow us to truly understand how they feel.

“The Dreamer’s Litany,” the stunning opening story in the collection, begins as follows: “On a warm Saturday night full of starlight, the man walked into Auwal’s shop and asked for a recharge card.” There is such hope and promise blooming at the start of that line, from that lovely description of the night—and we know, right from the start, that something will happen between these two men. There is also a striking juxtaposition between the natural world and the world of the shop, and that tension continues through the narrative.

At one point in the story, Auwal returns home to his wife and child after seeing the man, and he checks on his daughter, who is asleep: “The moon sprayed silver light on Aisha’s face.” Here, Ifeakandu initially expresses the love that Auwal has for his daughter in a beautiful and lyrical way, by using the natural world to show us what is in his heart. Later in the paragraph, Auwal expresses his love more directly: “Having her was the biggest miracle of his life; everything she did made him quiver with love, her smile, the excited voice in which she recited her three-letter words, the way she gripped his finger even in sleep.” By introducing his love for her through the moon’s gaze, we feel that love before we hear it from Auwal.

Later, as the relationship between the two men begins to tear apart, Ifeakandu shows us this first by showing us the uneasiness of the natural world: “The day was perfect before it shattered. First, morning, the sky unsure of its disposition, vacillating between gloominess and glaring brightness.” He foreshadows the end of the story when, there too, the physical world stands in for the emotional: “A great wind swirled toward him, blowing bits of paper and polythene off the rubbish heap, stirring dust, the darkness suddenly alive with things that spiraled toward his face particles that flew into his eyes.” How the landscape has changed from that opening sentence, when the world was full of starlight and hope.

In his metaphorical language, Ifeakandu often uses description to define character or understanding in interesting and unique ways. In “Where the Heart Sleeps,” Nonye returns to her father’s home, two weeks after he has died. Her father’s partner, Tochukwu, is living in the house; Nonye has a civil and yet complicated relationship with him. She describes him as “a man with his edges tucked in” and then later expands on that description: “Still, he was good looking, in the way that a well-tended lawn is beautiful, purposefully.” It is so easy for us to see Tochukwu through this description, and it serves to show us who he is both physically and emotionally. Of course, we also get a sense of Nonye through this description, as we are seeing him through her eyes.

Later in the story, we are in Tochukwu’s point-of-view, and he has a sharp understanding of events that will follow: “It hit him like a sudden shard of light at a precarious bend on a dark road, the extent of his powerlessness.” An image like this resonates deeply with the reader—we can feel the way Tochukwu understands his current situation because we can see it. If he had simply understood “the extent of his powerlessness,” it wouldn’t carry the same weight. We can see the light, suddenly illuminating a dark stretch of a road, showing him what’s to come.

At times, emotions in the collection take the shape of things that exist in the world. In “Michael’s Possessions,” Obinna returns to his former home, where his ex-wife lives, where photos of their dead son are prominently displayed. He is there to retrieve some of the objects belonging to his son, a boy he was not able to say goodbye to before he was buried. He still pays the rent on the house, transferring money into his ex-wife’s bank account once a year. His sadness has a vague shape and weight: “he senses the shape of a familiar sadness, the same sadness that enveloped him after each transfer.” But his anger is far more defined: “As though his anger were a candle burning steadily in the dark, its boundaries precise and definite. As though it were not an inferno.” Providing an identifiable shape to an emotion makes it real and brings it alive, for both the character and the reader.

In “Mother’s Love,” a beautiful story that examines the complicated relationship between a mother and her son, the mother comes to visit her son, Chikelu, just two weeks after his partner has moved out. Chikelu is still reeling from the departure: he “still felt the weight of the loss lodged in his chest like a smooth and perfect pebble.” He can’t speak to his mother about this, about the way that he feels, so he holds the loss deep inside. And yet it is not a jagged rock with sharp edges: it is “smooth and perfect.” We know this kind of emotional pain, the bruise that keeps being pressed, the hurt that returns again and again, that, in its own way, becomes a kind of comfort.

The point-of-view then switches to Chikelu’s mother, and she watches her son as he, in turn, watches television. She notices “the way the light fell on his body, blue and soft, the way it made him look sad.” We see how his mother cannot admit to herself that Chikelu is sad—even though we imagine that it must be obvious; it is simply the light and glare from the television that effects the way he looks. There is an undercurrent here of the tension between the public and the private, the outer and the inner. His mother, even as she knows her son is gay, cannot allow herself to believe it, just as she cannot believe that he is sad. It is simply the light, covering his body in shades of blue.

Later, we are back in Chikelu’s point-of-view. It is evening: “Outside, night was descending, dimly blue.” His mother has discovered his truth, has learned that his partner has moved out. Chikelu has retreated from his family, and his sister comes to check on him: “She looked at him, her eyes sad, or maybe it was the dying light.” The echo here is unmistakable: Chikelu is unable to discern whether his sister is sad, or whether it is the late day light, casting its shadow. Both Chikelu and his mother are unable to speak their inner truths to each other; they turn, instead, to the outside world.

Ifeakandu’s description of the landscape is often breathtaking in its beauty; setting and place is integral to each of these stories. This is true, too, in “Happy is a Doing Word,” which details the journey of the relationship between two boys, Bineyelum and Somadina, as they grow into men. Bineyelum remembers a moment from when he was a ten-year-old child— a plane crash was featured in the evening paper. He reads the story with his father, then runs to his friend Somadina’s home to show him: “It was evening, the sun, huge and yellow, rolling into the belly of the sky.” We can see how the child’s perspective is colored by the adult’s remembrance. A child’s sun might be static, as seen in a drawing, but the adult Bineyelum sees the sun in motion, views the horizon as a belly. He remembers the moment with his friend, of course, but he remembers it as attached to the landscape. The memory does not exist without the place.

Later, when they are older, Bineyelum is living away from home in Lagos, Nigeria. He and Somadina are estranged, and when he talks to his family on the phone, he hears the gossip and the news from home. As he looks out his window at his neighborhood, he realizes: “It was so much like home, the riot of everything, the splattering of crumbling, brown-roof bungalows around that one compound ringed by flowers, the compound in which he now stood, looking out at all these people.” Lagos may look like home but it is not home: we feel his homesickness and his longing in the way he describes where he now lives.

The story moves almost seamlessly between the two men, showing how their paths have diverged but also, at times, how their experiences mirror each other’s. The fourth and final section of the story begins: “There were birds on the trees outside the Enugu Premier Secondary School where Kamara broke up with Somadina over the phone, and on the trees under which Binyelum stood, months after his settlement, scrolling through Facebook as he waited for his bus to arrive.” The trees and the birds are different, of course, the two men living different lives in different cities, but the sentence and the landscape tie them together. When they were children, they often sat under a tree, watching birds. But unlike the two men, the birds have the freedom of flight, the ability to move about easily, to leave one place for another.

Throughout this collection, the physical world often stands in for the emotional, the landscape often serving as the only thing through which a character can see the truth. In “Good Intentions,” a story written in the second person, the landscape sets the stage for the story to come as the narrator takes an early morning walk:

It is not yet daybreak, the full moon is receding, the pavement glowing with its borrowed light. It is a perfect morning for this. It has rained all night and the air is quiet and smells of kneaded earth. Tall trees flank the tarred road, long branches reaching out like desolate lovers, and when the breeze rushes through them, they shake the water off their bodies and it falls on you, a blessing.

In this description of the world around the narrator, there is beauty and heartbreak, revealing his inner state. The trees become lovers, and as they shake their limbs, droplets of water rain down, returning him to the physical world. All of Ifeakandu’s stories feature this movement between the physical and the emotional, the exterior and the interior. His gorgeous prose allows us to see the worlds his characters live in, and to see their inner worlds as well, the two working in conjunction, one world always bleeding into the other.