The Story of a Text Conversation in Bury Me, My Love

On Saturday morning—around six a.m.—I get a text notification. I’m not supposed to be awake at six. No one who would text me is supposed to be awake at six, and so some lizard part of my brain hears that sharp ping of a text alert and jolts me awake, thinking: “Something has gone wrong.”

I think at this point we’ve had our cellphones for long enough where we’ve developed a type of language with them. We know the type of call we’re getting when we feel our phones vibrating at ten a.m. on a Monday, or that when we see our screens light up with thirteen text notifications in a string of seconds we know they’re from that one friend who refuses to type multiple sentences into a single message.

For that six a.m. text, that language was right. The text was from Nour and she was panicking about how she’d overslept and missed the bus that would’ve taken her to her flight out of Beirut. I start texting her back suggestions: what about that friend who owes you after you delivered his baby? He’s nearby, right?

Another minute goes by before I hear back. Her friend says he can get her to an airport but he’s in Jordan. More specifically, he’s in Zaatari, the second largest refugee camp in the world. Adnan insists that he can get out of there and he tells her that he could get her to the airport nearby in Jordan and, well, Nour’s options are limited.

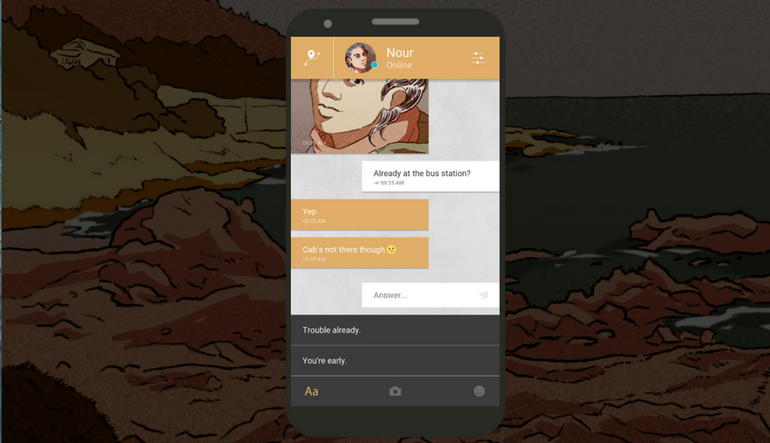

Nour is a Syrian refugee in the midst of fleeing her home and finding a way into Germany to request asylum. She’s also the protagonist of the phone game Bury Me, My Love. The game follows the experiences of a married Syrian couple, Nour and Madj, as Nour alone has to be flown, driven, smuggled, and marched across the Middle East and Europe to find a safe place to call home.

We assume the role of her husband, Madj, who must stay behind in Syria to take care of the few aging relatives he still has and through that we’re aligned into a shared narrative perspective. As Nour’s travels play out through the texts we receive, the advice we give her, and the selfies we send back and forth, things go wrong. As players, we bounce between reading the couple’s texts and choosing which texts Madj ends up sending. Nour texts us to ask whether she should pay a cab driver extra to take her to her original destination, or she texts us about where she should hide her money on her. Every option feels heavy and deliberate as together we make the plans that we think will get her away safely. However, plans don’t work and as she puts herself in danger, we’re reminded that texting is all we can do.

Phones have become such an essential part of a daily life with so many social interactions funneled through them that rather than removing any type of weight they might have had, we’ve created new venues for different emotional experiences. We’ve in turn changed the shape of the stories that surround our relationships—a friendship can be tweeting at each other to shit talk a show or a romance could be a one a.m. texted confessional.

The experience Bury Me, My Love focuses on is that silence when you’re waiting for a text. For two weeks, the game plays out in real time which means that when Nour texts you that she’ll talk to you in the morning, you have to wait until tomorrow. The game looks like the messaging phone app WhatsApp, the message app primarily used by immigrants all over, and when she does text you, you get a push notification like you would any other message.

The simulation is perfect down to the feeling in the pit of your stomach as you wait for a text. A text can be good but that wait provides you a space to think on all the things that can do wrong. Did I do something wrong? Are they mad at me? Am I annoying? Or, as Bury Me, My Love constantly circles back to, did something bad happen?

Older mediums have struggled with how to incorporate cellphones into their stories. There’s something about a texting conversation that looks wrong and inefficient in a novel that keeps them stuck reading like an artificial transcript. Films and television let people have them and use them but a phone can’t replace the visual weight of people talking in the same room—after all, who wants to look at somebody else’s screen as they’re already watching a screen.

Yet the lack of fictional validation doesn’t change the emotional experiences that are shaped by these pieces of plastic. After the first few days of Nour’s journey, after a few surprise border closures and bus cancelations, Nour ends up meeting a smuggler who would be able to get her into Bulgaria. Getting into Europe was good but if she was found by the military or the police in the wrong country, she’d be locked in a camp and forced to sign an asylum request that’d only get rejected.

Just to get into Bulgaria, she’d have to hike all night through the forest and mountains. She’d be with other families, sure, but if a baby started crying at the wrong time or someone got tired too soon then it’d be over. The whole thing would be for nothing. A few minutes before she started the hike, she texts me. She needs to save her phone battery, she says. She’s probably going to lose cell service anyway. I send a kissy emoticon and we say goodbye.

The next morning I check my phone but there are no notifications. I go about my day, go to the grocery store, do some laundry, and every text sound my phone makes I jump at it, thinking that maybe it’s her. It’s not and after a while I open the app, checking to see if maybe its bugged, but I see Madj type a desperate call, asking if she’s there.

Another day goes by. Then another. Three days go by before I hear from Nour again and things have gone bad.

This nightmare is something that immigrants all over have to go through every day as they wait in silence to find if their friends and family have actually made to their places of asylum. Dana, a Syrian refugee and editorial consult on Bury Me, My Love, told her story of immigration through her WhatsApp messages in the French publication Le Monde (if you can read French), and while that perspective makes the game feel real, it’s that delay in disconnection and reconnection of a conversation that makes us experience the narrative.

There’s been criticism for how “over-connected” our modern technology makes us—that we’re too tuned in to each other’s lives—but we can’t lose sight of the fact that it is still a connection. Even days later I’m still thinking about Bury Me, My Love, about the photographs she sent from the road, and Nour and Madj talking about their favorite songs. I’m thinking about it all because I was left waiting on a text.