The Subtle Interrogation of Power in The Pillow Book

The Pillow Book was written over a thousand years ago by Sei Shonagon, a lady-in-waiting to Japan’s Empress Teishi. It’s been an acknowledged classic for centuries, and yet readers still struggle with its unusual form, a nonlinear structure combining many different types of personal writing, including anecdote, memoir, essay, aphorism, and reverie. Not quite a diary or journal, not really a memoir, The Pillow Book stubbornly refuses to fit a ready-made category—refuses to be anything other than what it is: an unapologetic emanation of Sei Shonagon’s personality. As such, it somehow manages to feel intensely intimate without ever becoming particularly introspective. Instead, it makes the writerly argument for the emotional resonance of surfaces.

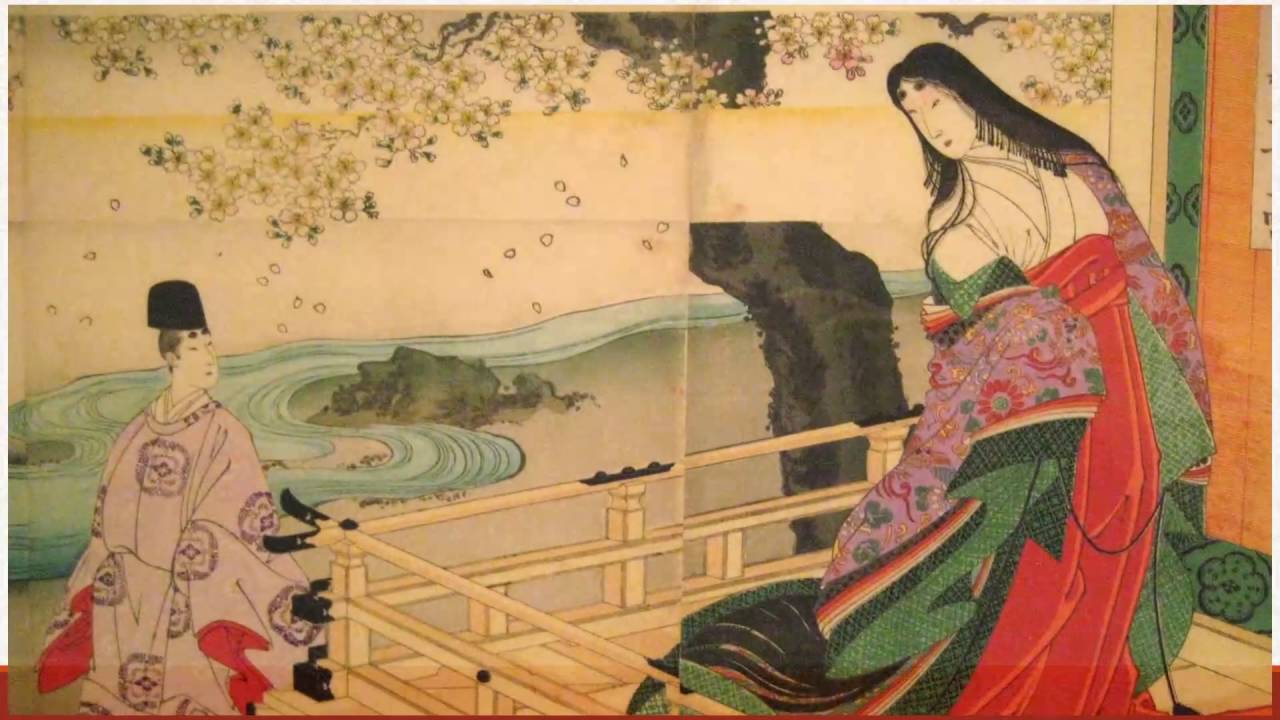

It’s possible to wonder whether the author’s mode of life was an influence on the book’s construction. In the Heian era, aristocratic women lived in a kind of purdah, hidden behind curtains and screens, an arrangement that didn’t blunt the male gaze so much as intensify it to the point of shared obsession, saturating court life. People of both genders were fascinated by what they could see through the holes in a lattice or the gap in a hedge—a man’s cherry-red hunting cloak, say, or a woman’s hazy but elegant figure bent over a scroll. Women coopted the rules of modesty for their own uses even as they conformed to them, arranging the brightly dyed hems of their under robes so that they were visible in the space between curtain and floor, and hanging their long colorful sleeves outside the windows of their carriages as they drove through the capital. Who was the man in the cherry-red hunting cloak? Who was the woman with the long peach sleeves? Encounters between men and women were a form of interpersonal collage, assembled from disconnected bits of data that could be combined in many different ways.

The Pillow Book feels like it arises naturally from that experience, the work of a writer utilizing gaps in genre boundaries to reveal herself through seemingly casual, but, in fact, carefully orchestrated glimpses. It opens with a list of Sei’s favorite times of day (“In spring, the dawn…In summer, the night”), followed by a breathless account of visiting the Imperial Palace for the new year celebrations (“What lucky women, I thought, who could walk around the Nine-Fold Enclosure as if they had lived there all of their lives!”), followed by an anecdote about roughhousing in the women’s quarters that may contain an oblique self-portrait (“There was a woman in the house who was in the habit of lording it over everyone”), followed by a weird and awful story about a dog that runs afoul of the emperor’s cat and is beaten and banished from the palace grounds (“When people talk to me about it, I start crying myself”). The book sometimes passes itself off as a manual for elegant living, giving us Martha Stewart moments on how to be à la mode circa 1000 AD (“A preacher should be good looking,” “Oxen should have small foreheads”), while still signaling that there is more at stake under the surface. But what, exactly? Shonagon refuses to tell us, saying only that she is interested in okashi, amusement. But if life at court is so unfailingly okashii, why then are we left feeling so uneasy?

The reason is that The Pillow Book’s true subject is power—more exactly, the experience of powerlessness. For aristocratic women of the Heian era, court life was competitive and precarious, subject to the whims of those stationed above them, and always carrying the risk of humiliation and rejection. Stories of beautiful and talented women who ended life forgotten and alone were a sort of black-market emotional currency circulating through the palace halls, a way of paying forward the fear hidden beneath all the fun. Sei’s patroness, the Empress Teishi, for example, was really just one of two consorts competing for the emperor’s favor, both of them dependent on family backing and glittering cultural salons to attract His Majesty’s affection and produce an heir to the throne. But Teishi’s fortunes crumbled when her politically influential father died; her brothers were exiled, and she lived only four more years, dying at twenty-three after a series of mortifications and indignities. Sei, a widow of forty by that point, left the palace and continued writing her book, her “pillow,” which morphed from a celebration of court life into a bittersweet and complicated remembrance.

Consider again that story about the palace dog who runs afoul of the emperor’s cat. In fleeing from the dog, the cat disturbs the emperor, who orders that the dog, Okinamaro, be banished from the palace grounds. “Poor dog!” mourns Sei in the classic 1967 translation by Ivan Morris. “He used to swagger about so happily.” She recalls how he attended royal festivals with a garland of peach blossoms on his head, cherry blossom strung around his torso, and then asks, “How could he have imagined that this would be his fate?” Apparently, he can’t imagine: he tries to come back, is beaten unconscious by two court officials, and then thrown outside the gates for dead. Teishi’s ladies-in-waiting are devastated, but later that evening, a different dog arrives outside their quarters, his body “fearfully swollen,” his face unrecognizable. He won’t accept food, won’t answer to his name, but when he overhears Sei recounting his story to the empress, something strange happens: “He started to shake and tremble, and shed a flood of tears.” Okinamaro! The women are delighted at his survival, and even the emperor comes to marvel. “It’s amazing,” says His Majesty, “to think that even a dog has such deep feelings!”

In the end, Okinamaro receives an imperial pardon and is restored to his former status—and yet something has changed for Shonagon. “When I remember how he whimpered and trembled in response to our sympathy,” she tells us, “it strikes me as a strange and moving scene; when people talk to me about it, I start crying myself.” This response is more than simple kindness: she has witnessed firsthand how unreliable imperial favor is, and how those who lose it suffer because they have lost not only their jobs but their identities, their exquisite aristocratic selves. Soon enough, that would be Teishi’s fate, and her own—though with characteristic restraint she says nothing about that part of her story.

It’s interesting to consider the connection between this theme of power and The Pillow Book’s formal hybridity. When Okinamaro returns after his beating, he makes a point of not responding to his name: his plan is to pass himself off as an entirely different dog. In the same way, Sei claims to be writing harmless vignettes of court life, and when that pose stops being useful, switches to writing a poetry manual, and then a handbook on elegant living, and then a sort of dating guide for Heian women—all the while addressing her interest in who controls who on the level of subtext, slantwise. Of course, no other approach would have been conceivable for a lady-in-waiting, a woman whose employment correlated entirely with her ability to charm. Her magpie aesthetic is the method of choice for people who feel they don’t occupy the big central narrative of their time, who have to assert themselves and the value of their experience indirectly, through implication, irony, and wit.

As a result, The Pillow Book feels unexpectedly relevant to our current literary scene, despite the sheer foreignness of the world it describes—a progenitor of the fragmentary, nonlinear, hybrid-genre work that has been energizing the memoir for a while now. It is heartening to think that a tenth-century Heian aristocrat who spent much of her time trying to peek through bamboo blinds at the world beyond the women’s quarters might share a kind of spiritual kinship with writers such as Maggie Nelson, Anne Carson, Claudia Rankine, and Ross Gay. But the truth is that Sei has important things to offer us. There is her bravery, her sneakiness, her openness to the quirkiness of her own reactions to life. In particular, there is her awareness of beauty, which is tied to her belief in the power of language to capture the fleeting nature of experience. In The Pillow Book, the world’s sheer loveliness becomes a countervailing force, an antidote to the workings of power.