The Trials of Migraineurs

It was my first spring in Virginia. I had returned to campus after winter break and was met with green lawns and trees that sparkled with blooms, a lushness California live oaks hadn’t prepared me for. Sitting on my bed after dinner a few days later, I began to feel like my leg was asleep, but I couldn’t shake it awake. The numbness traveled into my stomach, where it made my intestines feel cumbersome and confused, then deadened my arm and threaded its tentacles up my neck. One side of my body was completely numb. Still, I set off across campus to meet up with friends, who were shocked by my slurred words and disorientation. I mumbled that I was okay, but as I tried googling what was wrong with me, I found that I was incapable of formulating a question. My friends called the EMTs, and when they asked for my home address, I wasn’t sure if I’d gotten the street numbers and zip code right for a house I’d lived in for more than a decade.

The EMTs recommended rest, so I begrudgingly returned to my dorm room, where the numbness dissipated. In its wake came a pain in my head that screamed my brain awake; I asked a friend to drive me to the ER sometime after midnight. After undergoing scans, vomiting, and being given a narcotic so strong I slept through the entire next day, I was told that nothing seemed to be wrong. I went home and didn’t tell my parents about the episode until two days later when it struck again. They arrived thirty-six hours later, and we began the process of figuring out what was happening to my body. I saw a neurologist, who answered in one word: migraine.

Migraines are hardly rare. Thirty-six million Americans experience them, though they disproportionately affect women—three women for every man. Some of us migraineurs and migraineuses are luckier than others—only a couple migraines each year or two—while others suffer the pain daily or close to it. In fact, the ADA classifies migraine as a disability for those whose treatment-resistant migraines result in chronic pain. In addition to this pain, migraines encapsulate some less-known elements, more unique elements. Migraineurs sometimes experience an aura, usually ocular or sensory disruptions, like a squiggle of light across one’s vision, which writer-neurologist and migraineur Oliver Sacks describes in his 1970 book, Migraine, as “the many weird and wonderful symptoms which commonly precede the headache of migraine.” Migraines have a litany of common triggers—red wine, chocolate, avocado, cheese, stress, dehydration, and exhaustion, to name just a few—and many so-called miracle cures. For people with uteruses, migraines often correlate to puberty, birth control, and menopause.

You would think that such an experience—such a common experience—would automatically legitimize the migraineur’s pain and medication use. But every migraineur has heard the anecdotes and advice non-migraine sufferers have trotted out—whether well-intentioned or critical—belying a lack of understanding of migraine pain, its origin, and its remedies. “Just drink more water!” some say, while others announce that they have a high pain tolerance, insinuating, or saying explicitly, that the migraineur is weak for acknowledging their pain, or medicating it. I feel like I have a high pain tolerance, too, but the severity of the pain I feel from a migraine leaves me unable to perform my job or necessary daily tasks: in addition to the pain in my head, I also experience nausea, sensitivity to light and sound, irritability, and disorganized thought. I can do my job or I can be in pain, but I can’t do both. Nor can I will away the pain—as invisible as it is, and as easy as it is for non-sufferers to call the pain into question—I can only muscle through its knifing presence for so long. Many non-migraineurs mistakenly conflate headaches and migraines. To be clear, the pain of a migraine is different. For me, a headache is a dull, diffused throb cured by time or over-the-counter meds like Advil or Tylenol, which do nothing to touch the pain of the more insidious, vice-like migraine and its attendant effects. Still, the insinuation of weakness in migraineurs—a defect of character—lingers, fermenting into shame and anxiety in many of us.

I wasn’t 18 the first time I had a migraine—I was four, too young to understand the pain or its stigma. I remember that first migraine and my inability to comprehend the pain’s source since I hadn’t bonked my head on the corner of the kitchen counter like I had a few times before. Eventually, I fell asleep on our denim couch in the bright light of the afternoon, and when I woke up, it was to the golden light of dusk, which confused me even more. How had I slept time away like this when it wasn’t naptime or bedtime? And where had the pain gone? I don’t remember having another migraine until second or third grade, but from then on, they were bad. These migraines made me vomit, and brain scans, unsurprisingly, revealed nothing. Only later did I learn that my dad, aunt, and maternal grandma had migraines. But they were lucky ones, only a migraine or two a year, and the frequency and intensity of mine didn’t look like what my parents knew about migraines in our family. My migraines were idiopathic: they could strike at any moment, leaving me marooned on my bunkbed during overnight field trips or languishing on the nurse’s table until one of my parents brought my medication to school (though eventually we broke that rule and I kept Advil in my backpack—the migraines were just too frequent).

For fourteen years, though, I’d never gone numb and lost the ability to speak and think. So at 18, when the Virginia neurologist, bored by such a simple diagnosis, said migraine and chalked the numbness up to aura, my family and I were incredulous. The neurologist wiped his hands of looking further into the sudden change in my migraines, but we were unassuaged by his speed, disinterest, and prescriptions for Imitrex and Topamax—my first prescription drugs for migraines. There had to be something else going on, and there was. My mother ultimately cracked the case: she watched the numbness hit me at dusk, which left me vomiting all night. I’d spend the next day recuperating indoors, then the day after I’d spring back to life, walking to classes and hanging out on lawns in the balmy spring afternoons. At dusk, it would happen again. My mother noticed the gutters so saturated with pollen it looked like someone had poured yellow paint down the drain, and that’s when she knew: the Virginia spring caused the aura. She got me into an allergist’s office that was booking appointments months out, and subsequent allergy testing revealed nearly forty seasonal allergies that left my blood churning with histamines. There wasn’t any quick fix, but at least we had our answer, the only one I’ve ever had for what’s triggered my migraines.

“Why, in the country (in the southwest of France), should I have stronger and more frequent migraines?” Roland Barthes asks in Roland Barthes (1977). “I am resting, in the open air, and yet more migrainous than ever.” I want to reach back in time and tell Barthes to cut out his solipsistic chatter. He wasn’t a “victim of a partial desire, as if [he was] fetishizing a specific point of [his] body”—he’d just figured out his migraine trigger: histamines. But I can understand why Barthes, like many others, may have second-guessed the veracity of his migraines, this extreme—invisible—pain. Even with the blinds drawn, lying on my bed with a cold washcloth across my forehead, I wonder if what I am feeling is real. Others, especially those who don’t experience migraines (or even headaches), doubt the realness of migraines, too, as fellow migraineur Joan Didion notes her essay “In Bed.” There was “nothing wrong with me at all,” Didion says, “I simply had migraine headaches, and migraine headaches were, as everyone who did not have them knew, imaginary.” It’s difficult to conceptualize this invisible pain and the ways it lays waste to the sufferer.

Class adds another dimension to the disorder; migraineurs are forced to negotiate functioning in a world that doesn’t slow down for their pain. “[W]ho ever heard of the proletarian or the small businessman with migraines?” Barthes asks. I’ve heard of plenty, but I can see what he means: migraineurs in the workforce don’t have time for a migraine; their jobs don’t grind to a halt with the onset of pain, so we have to find a way to work through them. I’ve slipped out of class to retrieve migraine medication from my office when I’ve forgotten to keep it in my bag. I’ve muscled—white-faced and nauseous—through faculty meetings rather than beg to skip them. The migraines happen too often and too suddenly for my life to be rearranged or put on hold to accommodate the pain. Migraines are disabling, but most of us have to find a way to squelch their ferocity enough to get by. Pain holds the power, as Lisa Olstein calls attention to in Pain Studies, her examination of pain, including migraine pain. Olstein lays bare the process (and panic) one goes through in determining what is possible to do after the migraine’s almost always unexpected onset: “Can I stand up? Can I drive? Can I work today? How long before I’m able? Then, for how long will I be able?” We don’t want to be weak and we don’t have time for this. Most of us can’t afford—financially, mentally, or professionally—to let the pain win.

Even though we don’t have time to waste, we try to think our way out of the pain before reaching for medication. As Olstein notes, the migraineur is drawn to the delusion of “magical thinking . . . the make-believe bargaining you can’t help but do. More than anything, it’s a means of proving yourself to you, rehearsing how much you don’t want this to be happening.” I’ve never been able to think myself out of a migraine, but I try to every time. When I finally acknowledge it, I gamble on a strategy to cure the migraine—combining water, sunglasses, physical therapy migraine exercises, rizatriptan, peppermint oil, and more—and hope my tactic is right so that I won’t get stranded somewhere when I should have been in bed. I don my sunglasses at work, brace myself against the hallway wall, muster enough energy to stand in front of my students, and do my best to shepherd them through writing concepts or a text. To do otherwise would be to fail—or that’s how it feels.

There’s a temptation, both culturally and personally, to unfavorably link migraine and character, which begets a migraineur’s shame. Barthes suggests that his migraine was rooted in character, contemplating migraine as both debased and sensuous, an affliction he “should agree to enter—though just a little way (for the migraine is a tenuous thing)—into man’s mortal disease: insolvency and symbolization.” For women, this conflation of disorder and character becomes alarming given how often women’s pain has been dismissed, especially when it’s invisible. Indeed, one sees the sexist rhetoric espoused in Didion’s time where a person that “tends to be ambitious, inward, intolerant of error, rather rigidly organized, perfectionist” has a “migraine personality”—qualities women were readily faulted for then as now, though they’re viewed as more excusable in men. Especially with rhetoric like this, the temptation to read into one’s pain is strong, and Didion laments what her migraines might be saying about her character. “That in fact I spent one or two days a week almost unconscious with pain seemed a shameful secret,” she writes, “evidence not merely of some chemical inferiority but of all my bad attitudes, unpleasant tempers, wrongthink.” Migraine becomes a catch-all for Didion’s faults, punishing her with pain.

While the inherently sexist theory of a “migraine personality” that was popular in Didion’s day has been rejected by modern medicine, it feels difficult to shake, especially when reinforced by medical professionals and those around me. Didion’s distress about what migraines say about her personality makes me think of my own character. I have a tendency toward perfection, fastidious tidiness, and low tolerance for errors; I’m an anxious person, neurotic, and high strung. I wonder if those around me think I am lying about my pain, using it to get out of things, and then I wonder if I’m faking the pain even as it bites into my brain. Just act a little tougher, I tell myself, go to the dinner even if your head feels like it will explode, see how long you can go without taking medication. When it comes to migraine medication, this line of thinking is especially problematic: when not taken at the onset of a migraine, the medication drops in efficacy so significantly that it often has no effect, leaving the migraine to throb unabated. Sometimes one pill or two or a combination of prescription and over-the-counter medications don’t eradicate the migraine, but not banishing the migraine completely may mean that the migraine will linger indefinitely. Too much medication, though, and you run the risk of rebound headaches. How much is just right, and how much are you willing to suffer? What are you willing to put in your body so that your body leaves you alone? Is it strength or masochism to wait to take meds? Does it matter what other people think? What does our use of medication say about our character? “I’d worry this is characterological, that I flee too quickly, too desperately into the arms of an immediate solution, be it Advil for cramps, migraine meds for migraine, epidural for this,” Olstein says after turning to medication for pain relief. “I worry this tendency—weakness, fear, lack of imagination?—might infect my parenting, as well.” In Olstein’s worrying, being quick to medicate swiftly goes from weakness to a deficient imagination, as if not only could she have been stronger, but she could also have been more creative in handling her pain without medication (or at least delaying taking it).

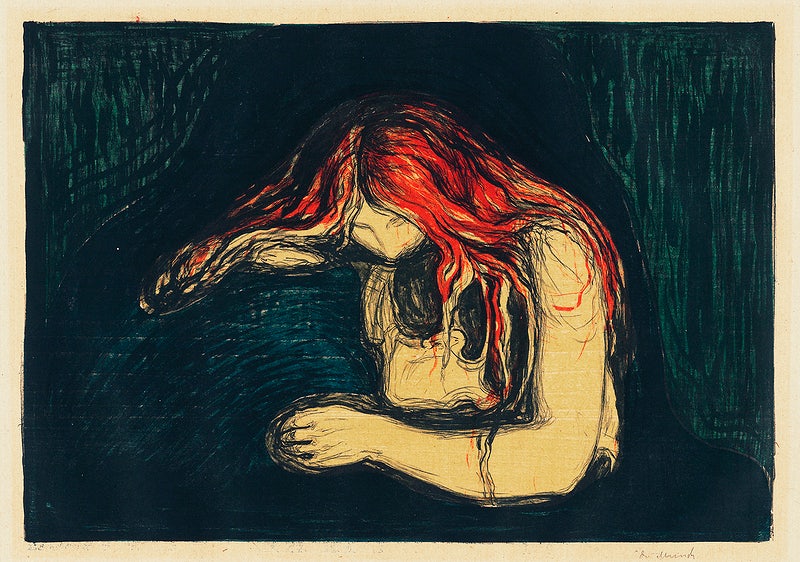

The migraineur cultivates her own creativity both in how she handles the migraine and in what happens in her brain during the space of time the medication takes to kick in. Oftentimes, the pain causes the migraineur to meditate on death. My brain began building a migraine-death-fantasyland when I was a child. I remember inhabiting it like a quilt I spread out to lay down on each time the pain hit. I’d settle into that desire for deadness in a landscape washed in the black of a closed closet during a game of hide and seek. The Grim Reaper was there, larger than life and faceless, holding a scythe and dressed in a black gown. I’d float in this blackness like it was my own funeral, and it became a form of comfort inside the pain. Comforting her son, Olstein tells him, “‘the headaches don’t actually hurt me . . . . They won’t kill me; they’ll never be what makes me die.’” Though she’s comforting her son, Olstein equally seems to be comforting herself. “When the days pile up, I start thinking about being dead—not suicide, really, a fantasy instead,” she says—the migraines won’t kill her, but death seems relieving in comparison. “That no one dies of migraine seems to someone deep into an attack, an ambiguous blessing,” Didion observes. It’s comforting—sort of—that the pain can’t kill you. So it might be more accurate to say that in the midst of a migraine one thinks about not being alive, a habit of thought that feels to me as much a part of the migraine symptoms as nausea or light sensitivity, which leads to an alternate universe. “[M]igraine is a space you enter and are enveloped by and it is a different version of the world in there,” Olstein writes. “Mostly, I imagine stepping from a roof; I’m not sure why. Maybe because it’d be breezy up there and sometimes a breath of cool, fresh air can provide a moment of relief from migraine’s hot, pressing hand. Maybe because the roof is the head of the body of the building.” We all have our own versions of the space we tread water in until we break through the pain.

When my pain finally breaks like a fever, my landscape vanishes, and my brain turns the technicolor of Oz. I feel suddenly invigorated, like I can bound up a mountain, and I marvel anew at my relief each time. Similarly, Olstein’s fantasy was “the pleasure of waking into a kind of bodilessness, which is sometimes how the clearing (that formal feeling) feels when it does finally come.” When Didion’s pain dissipates, “everything goes with it, all the hidden resentments, all the vain anxieties. The migraine has acted as a circuit breaker, and the fuses have emerged intact. There is a pleasant convalescent euphoria.” On the other side of a migraine, the body feels returned, restored to something better.

Beautifully, Olstein’s son tells her, “‘Mama, what I think of migraine is like a flock of migrating birds coming and hitting your head—not on the outside, but on the inside of your mind.’” Birds seem so much more lovely than the pickax, anvil, and fiery rods, among many more things we use to describe our head pain. For Didion, migraine is “a guerrilla war with [her] own life, during weeks of small household confusions.” Personifying migraine, Olstein imagines it saying, “I’m the paint and, baby, you’re the canvas,” a version of migraine that’s snappy, demanding, and in control with something pretty underneath—our brains become lit up with the color/pain, dayglo cinching across our craniums, tugging at our cheekbones and shoulders. “Does our pain define us?” she asks. “Only if it’s bad enough? Only if we let it? Only if we don’t have anything else going on?” The migraine pain visits unexpectedly at any moment, permeating our everyday lives.

Now, once a month, I hold a giant plastic apparatus on my thigh and click, feeling a fierce sting as a needle shoots into my skin, and I hope that this liquid I am injecting will hold the migraines at bay a little better than everything else that has come before. It’s one of the newest medications, and I’ve bargained hard with my insurance company to access it at an affordable price. With few side effects, unlike some infamous migraine meds, the drug promises to cut my migraines by fifty percent, though many users experience an even greater decrease. So far, I’m one of them. It’s hard not to still feel shame for opting for medication, both daily and as-needed medications, but as the migraines strike less, I’ve begun to be less afraid of them and their pain and the way they lay waste to my days. Migraineurs can’t always live an able-headed life, but we still find ways to soldier on, wrestling this ruinous pain and how others perceive us so that we may live as close to able-headed as we can.

This piece was originally published on August 17, 2020.