The Uneasiness of Lispector and Klassen Children’s Stories

The killing of the fish is not a secret. Clarice is upfront about that from the very beginning. I didn’t do it on purpose, she assures us, though we can’t be 100 percent sure she’s telling the truth. So begins the first story in The Woman Who Killed the Fish by Clarice Lispector, one of six books recently published by New Directions in their Storybook ND series. The books in this series are meant to be reminiscent of picture books—though the illustrations are minimal—described by the publisher as creating “the pleasure one felt as a child reading a marvelous book from cover to cover in an afternoon.” And indeed, the books are short (Lispector’s is only sixty-two pages), but they more than make up for it in depth.

Who better to write a children’s book than Lispector? The Brazilian writer’s work has had a recent public resurgence; we have been wowed as we discover or rediscover her writing by her seemingly pragmatic approach to the page, and by her characters, who appear confident in themselves and their thoughts even though, perhaps, they really aren’t. Her voice is the voice of a certainty that is often reserved for picture books, and her narrators always seem like they know what they are talking about. Much like how children’s books seek to persuade young readers that they are a voice of authority, Lispector too tries to gain our trust through her self-assured tone.

But Lispector’s work is also tinged with a hint of existential dread that keeps readers from really feeling comfortable amidst her sentences. This is where her relationship to children’s literature drops off—children’s literature, of course, is not supposed to do this to its readers. We want kids to want to read, so we try to avoid scaring them with unsettling endings. In fact, we have even changed endings to famous stories (like those by the Brothers Grimm) simply because we have deemed the originals to be too violent or scary or harsh for young minds.

The thing is, though—The Woman Who Killed the Fish actually was written for children. Lispector’s children to be exact. And even though it reads with the same kind of confidence as the rest of her work, she makes no attempt at softening her story, which is really a long-winded confession to her kids about how their pet fish came to perish.

In this way, Lispector’s work is most reminiscent of that of the picture book writer and illustrator Jon Klassen. Known for his hat trilogy, in which a series of animals go through the emotional process of losing, finding, and even stealing various hats, the animals that populate Klassen’s world operate with the same kind of conviction as Lispector. Klassen, too, does not seem to care if he makes children feel uneasy, and indeed, that is exactly the feeling one often has after finishing his books.

In I Want My Hat Back, a bear desperately goes in search of his hat. He’s lost it, and he wants it back, so he sets out looking for it, asking all of the other animals in his world (the stark white pages the animals populate cannot really be classified as a forest) if they have seen it, only to be told repeatedly that no one knows where it is. But what makes I Want My Hat Back so much fun is that while the bear and its cast of animal friends all say one thing, the illustrations in the story suggest something else entirely. If you are a clever reader, you will notice right away that one of the creatures that the bear encounters is not telling the truth about having seen the hat. In fact, he is flat out lying (boldly, since he is quite literally wearing the very hat the bear is in search of), creating a dissonance between what is being said and what is actually happening on the page. Of course, by the book’s end, the bear recognizes that he has been duped and revisits the rabbit who boldly attempted to get away with the thievery. The confrontation between rabbit and bear happens off the page, but in an ironic twist of fate, the tale ends with the bear, now wearing his hat, assuring us that he has not seen any rabbits and that he certainly would not eat any rabbits even if he had seen them. Having heard a similar thing from the rabbit only a handful of pages before, however, we have become wise to Klassen’s world and finish the book knowing that the bear most likely is not telling the truth.

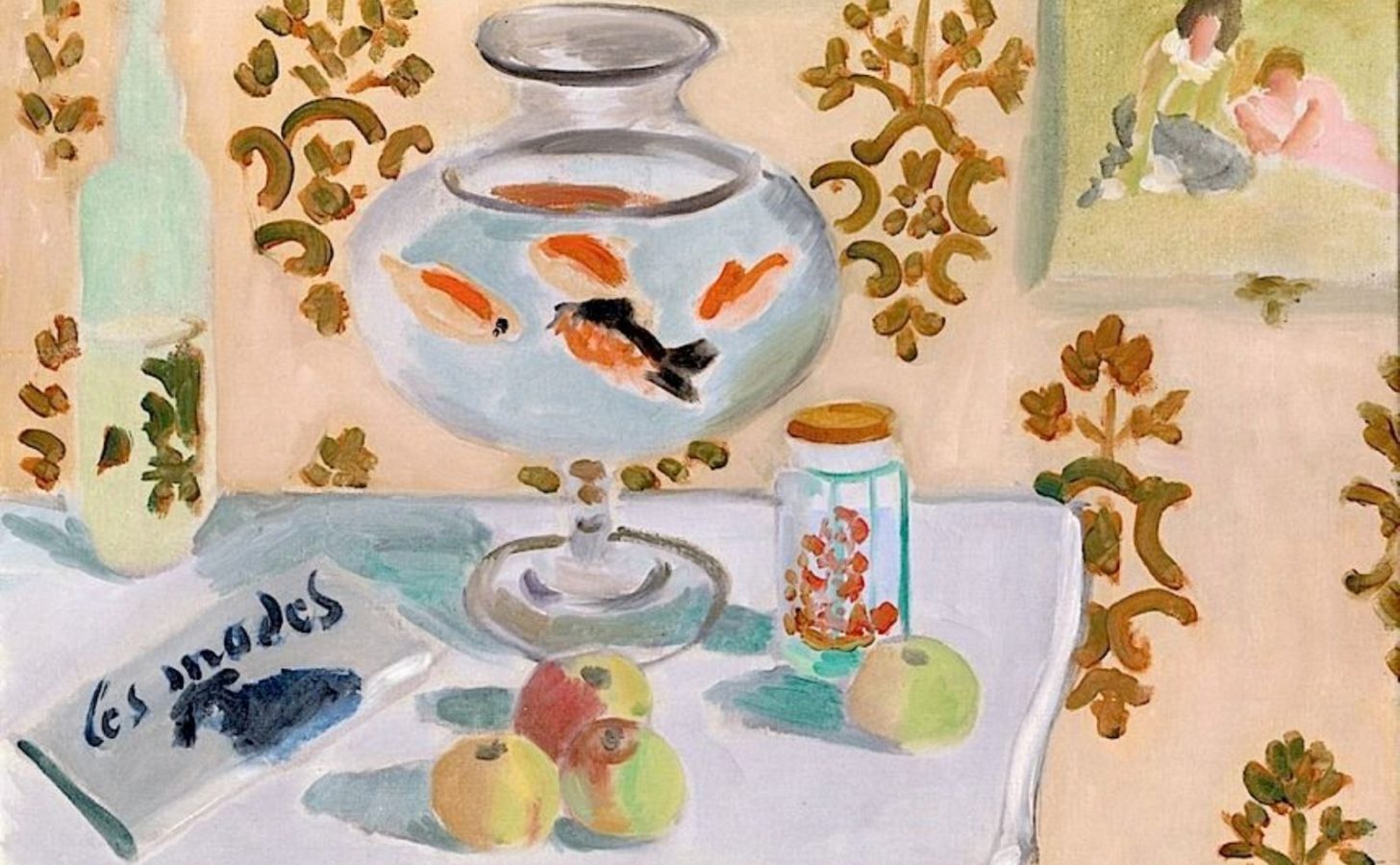

While I Want My Hat Back is funny and a little bit silly, there is also a strange undercurrent of violence and terror that exists in the book. Readers are taught that Klassen’s narrators do not always speak the truth and therefore cannot be trusted. It is only through their actions that we can firmly believe what is happening on the page. A similar situation occurs in the second book in the hat trilogy, This is Not My Hat, only this time, the fish—much like Lispector in The Woman Who Killed the Fish—is upfront about his crime from the very beginning. “This hat is not mine,” he tells us on the first page. “I just stole it.” Obviously, Klassen banks on his readers knowing that stealing things is wrong. He wants us to object to the fish’s actions from the very beginning. But the fish has other plans. He attempts to persuade us into siding with him, justifying his actions with all kinds of reasons why he should be the one to own the stolen hat instead.

In the end, the fish meets a similar fate as the rabbit. The fish who got his hat stolen finds him and, though we do not actually see the violence unfold on the page, presumably eats the thief in order to get his hat back. And just like in I Want My Hat Back, the juxtaposition of what is being said versus what is happening in the imagery creates a clear message to its readers that words, however good they might sound at the time, do not always equate to the truth. Klassen teaches his readers an important lesson about how actions sometimes speak louder than words, and he does this by filling his readers with unease by the story’s end. Yes, both the bear and the fish got their hats back. But in order to do so, they had to devour the animal who wronged them. What action is worse?

Lispector’s confession about killing the fish reminds me of This is Not My Hat. Both Clarice and the fish want you to side with them and their choices. They have a desire to be perceived as being not really as bad as they might, at first, seem. Lispector assures us that she is truly an animal lover, and she tries to prove this to us by telling us a series of stories in which animals came into and out of her life. But the stories she tells, though seemingly well-meaning on the surface, actually end up reading as kind of horrific when you look at them closely. The two dogs she owned and presumed to have loved so much were eventually given away, and the pet monkey that she purchased from a street vendor died a sad death shortly after being gifted to her family as a Christmas present. While she makes a case for herself as an animal lover, each one of her stories is tinged with a degree of unreliability that makes you question whether she really is. In the end, when she tells you how she just forgot to feed her children’s fish (and clean their bowl), we must ask ourselves if her negligence is just as bad as if she had meant to kill the fish from the very beginning.

Children’s books are supposed to be an experience for young readers. They employ conversational tones and ask questions of the reader to draw them in and make them feel like a part of the story. In short, they come to life on the page. Lispector’s work in The Woman Who Killed the Fish operates with these same mechanics, just like Klassen’s books. What sets these stories apart, however, is their unique approach to their subjects. Neither Klassen nor Lispector seem to believe that subjects need to be softened for children to understand them. In Klassen’s world, animals die for their sins—albeit off the page—and Lispector’s children learn that their mother may not be exactly as guilt free in the death of their fish as she wants to appear. Suddenly, instead of existing in a world of right and wrong, things become tinged with gray. Stealing is wrong, yes. But so is devouring another animal whole.

Ultimately, what makes Klassen and Lispector so appealing as storybook writers is that both of them make attempts at creating a world in which children aren’t shielded from complex situations. They understand that just because a person is young does not mean they cannot understand some of life’s darker aspects. A book, whether written for children or not, should do more than just infuse its reader with feelings of joy and happiness. It should make them think. It should, at times, make them uneasy. And above all, it should make them question—because questioning is so often where a story begins, even if it only happens at the end.