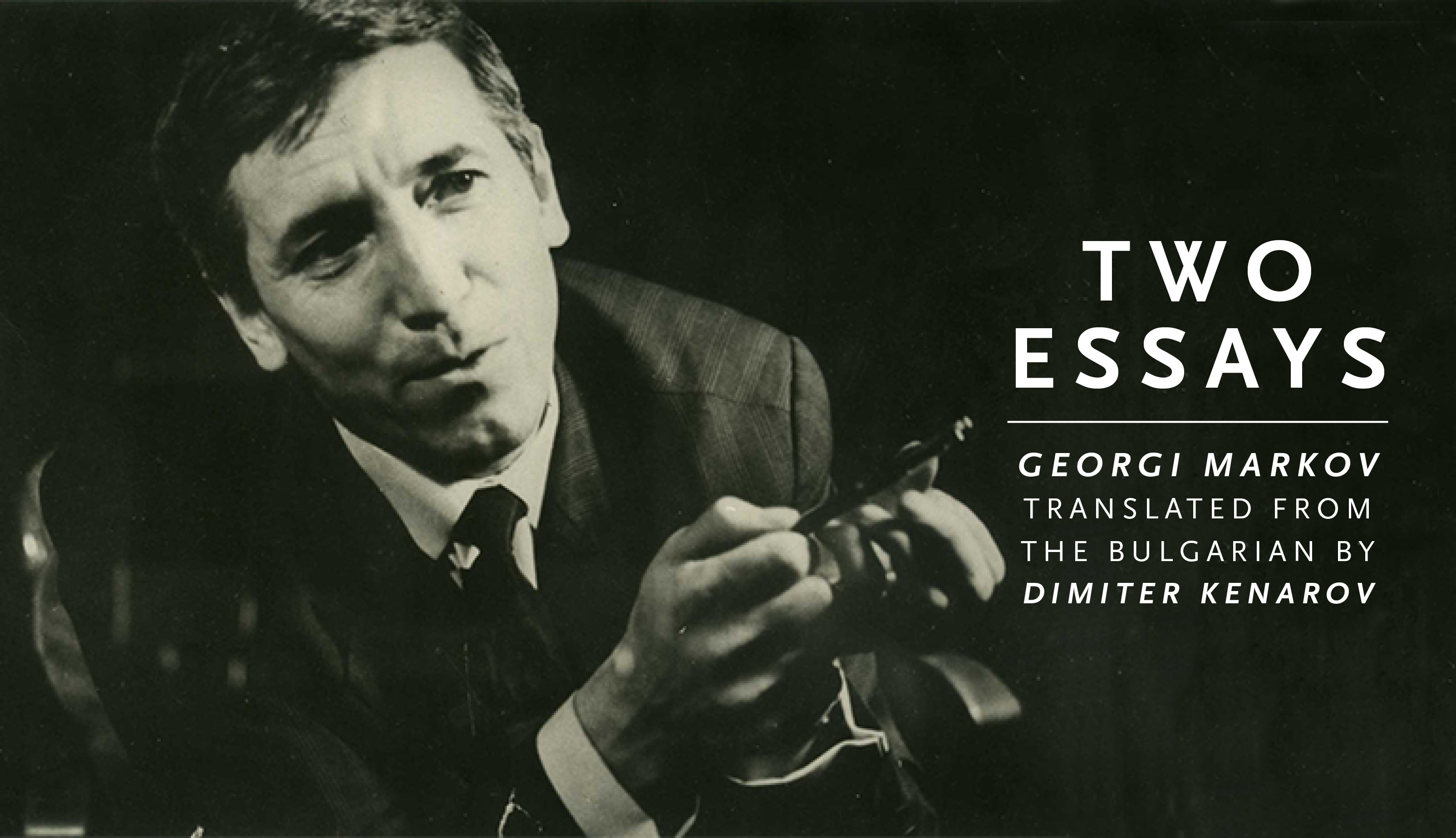

“Two Essays” by Georgi Markov, Translated and Introduced by Dimiter Kenarov

The following is an excerpt from the introduction to the latest installment of the Ploughshares Solos series: “Two Essays” by Georgi Markov, translated by Dimiter Kenarov, available now for $1.99.

When [Georgi] Markov moved to London in the summer of 1970, after a brief stint in Italy, he had no money and no connections. He rented two rooms of a house in a dingy part of southwest London and, with no steady job and no knowledge of English at first, had to rely on the generosity of a few acquaintances. Unlike literary émigrés from the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia, who enjoyed at least some public attention in the West and occasionally had access to university positions and translators, Bulgarians had practically no support networks. Of all the Soviet bloc countries, Bulgaria—the closest satellite of the USSR—was the least known and considered the least interesting. Markov, the Bulgarian writer, stood little chance in his newly adopted country.

Yet he doggedly persevered. He quickly learned the language and eventually found a job as newscaster at the BBC’s Bulgarian service. Soon, he also began to contribute regular cultural and political pieces on Bulgaria—increasingly critical in tone—for the Cologne-based radio Deutsche Welle, broadcasting on short wavelengths to audiences behind the Iron Curtain. It was Markov’s series of personal narrative essays for the US-sponsored Radio Free Europe, In Absentia Reports About Bulgaria, however, that put him directly in the line of fire of State Security (the feared intelligence service back home) and turned him into one of the most reviled and dangerous enemies of the regime.

With channels for free communication with the countries of the Soviet Bloc effectively closed, radio was often the easiest and most reliable means for delivering information to citizens there. It was the reason socialist governments viewed all radio broadcasts coming from the West as conduits of “ideological sabotage”—one of the worst possible crimes in their handbook—and relentlessly jammed their frequencies; in spite of this, millions of people found ingenious ways to tune in.

Markov’s indefatigable radio work was seen as particularly incendiary. His In Absentia ran weekly from November 1975 to June 1978, for a total of 137 installments (two of which have been translated in full here), and quickly gained popularity in Bulgaria. Eloquent and engaging, written in the best tradition of narrative journalism, his essays offered an eclectic mix of personal memoir and overheard stories, vivid human portraits and entertaining anecdotes, popular history and philosophical analysis. As a former insider, he openly acknowledged his once privileged role in the system and went on to expose the secret lives of high officials and party functionaries, intellectuals and artists. However, he never forgot the people from “the lower depths,” those on the margins, to whom he devoted some of his most colorful pages: factory workers and university students, prostitutes and tramps. In effect, Markov produced what was the most candid, incisive and comprehensive portrait of Bulgaria under communist-party rule, from the end of the Second World War until the late 1960s.

Dimiter Kenarov is a freelance journalist based in Sofia, Bulgaria. His articles have appeared in Esquire, The Nation, Foreign Policy, VQR, and The New York Times, among others. He is currently at work on a book about the Bulgarian writer and dissident Georgi Markov (forthcoming, Grove/Atlantic).