Van Gogh’s Letters

In the summer of 1873, twenty-year-old Vincent van Gogh arrived in London, eager to continue his work with the international art dealers Goupil & Cie; for the next three years, he would live and work primarily in England. This period is the subject of the Tate Britain’s current exhibition, “Van Gogh and Britain,” focusing on the painter’s time in London and the various influences he encountered while there as well as the impact Van Gogh had on British artists through the 1950s.

In the summer of 1873, twenty-year-old Vincent van Gogh arrived in London, eager to continue his work with the international art dealers Goupil & Cie; for the next three years, he would live and work primarily in England. This period is the subject of the Tate Britain’s current exhibition, “Van Gogh and Britain,” focusing on the painter’s time in London and the various influences he encountered while there as well as the impact Van Gogh had on British artists through the 1950s.

From his time in London, it would be another seven years before Van Gogh decided to pursue his calling as a painter, but, as the exhibition makes clear in a variety of ways, these early days were critical toward his laying a foundation for it. A look at his letters from this time, and throughout his short but productive life, shows that even before he began to devote himself to painting, he was gathering layers of experience that provided a way of seeing far beyond the inspiration that the works of painters he encountered provided him—much of his influence at the time, we learn, came not from British artists but from literary sources. In an 1874 letter to his younger brother and confidante, Theo, Vincent admits that “my interest in drawing has died down here in England, but maybe I’ll be in the mood again some day. Right now I am doing a great deal of reading.” The Tate’s exhibition builds upon this idea from the first room, in which viewers encounter a row of volumes by British authors that Van Gogh read and whose influence he welcomed. The books, bound in uniform red, include Charles Dickens, George Eliot, John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, John Keats, William Shakespeare, and Thomas Carlyle.

“Admire as much as you can, most people don’t admire enough,” he exhorts his brother. Van Gogh often expresses his admiration in terms that would seem not to fit with this wide inundation of influences. Take, for example, a reaction when he takes a walk with his sister, Anna, who had joined him in town as she looked for a governess position: “It is so beautiful here, if one just has a good & single eye without too many beams it. And if one does have that eye, then it is beautiful everywhere.” What manner of seeing is this for a twenty-year-old aspirant with doors thrown open to the world? It was clouded with ambiguity from the start.

At this time, and throughout his life, Van Gogh expressed a desire for unity within the plural influences of nature, art, and Christianity. In 1875, he tells Theo that a “feeling, even a fine feeling, for the beauties of nature is not the same as a religious feeling, though I believe these two are connected. The same is true of the feeling for art.” His religious impulses increased as his interest in the business of art was beginning to ebb, and, after his dismissal from Goupil, he served a short stint as a teacher and then as an assistant preacher at a Methodist church in Isleworth. The first sermon Van Gogh delivered, which he copied out in full and sent to his brother, lends some insight into the way of seeing that he was cultivating at the time:

What is it we ask of God—is it a great thing? Yes it is a great thing: peace for the ground of our heart, rest for our soul—give us that one thing and then we want not much more…We want a Father, a Father’s love and a Father’s approval. May the experience of life make our eye single and fix it on Thee. May we grow better as we go on in life.

It is not difficult to read biographical longings into these words, particularly with respect to Van Gogh’s relationship with his own minister father, who, with early prescience, cautioned his eldest living son not to forget the story of Icarus. As his inner life increased in complexity, Van Gogh’s own desire for spiritual unity and simplicity mixed with the subjunctive wish to become better with experience. Together, these are ideas that he would not abandon, even in the tumultuous final decade of his life as a painter whose work no one appreciated enough to wish to acquire.

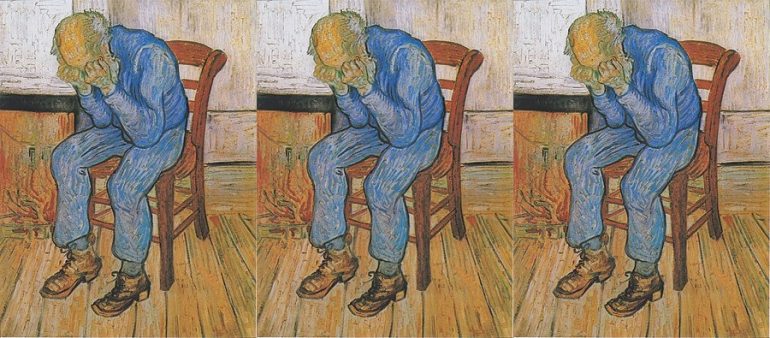

Several rooms in the Tate’s exhibition reveal variations on these expressions of seeking, of progress and frustration, featuring work from a range of dates— intense self-portraits, paintings of atmospheric roads with figures moving toward the vanishing point, drawings and prints with figures in various positions of weariness and defeat—that, together, give a collective impression culminating in the painting At Eternity’s Gate (1890). The distance that a hidden face and closed-off gesture creates in combination with the normally peaceable combination of light blues, whites, and yellows heightens the anguish of the piece. This is the Van Gogh we’re used to thinking about.

As the religious impulse blended more deeply with Van Gogh’s aesthetic pursuit, becoming nearly indistinguishable from it, the artist’s hope to become better through living would develop a new component. When Van Gogh moved to the south of France in 1888, foremost on his mind was building an art community in Arles. This vision of a productive group of artists living and working together, which he makes so much of in his letters, has always been at odds with the story of the artist as a tortured-isolated-wounded-genius. In addition to Paul Gauguin, Van Gogh was regular contact with Émile Bernard, Georges Seurat, and many other contemporary artists. In Arles, he painstakingly arranged the house not only for himself but with guests in mind. Again to Theo he writes, “for visitors, there’ll be the prettiest room upstairs, which I shall do my best to turn into something like the boudoir of a really artistic woman.” There, he packed the walls with the sunflower paintings he had been working on.

The Tate exhibition includes a room devoted to one of these paintings, on loan from the National Gallery. It is surrounded by lesser works of the many artists it has since inspired. Even though the paintings would not sell during his lifetime, Van Gogh, writing to Theo, is confident that “the day will come, however, when people will see they are worth more than the price of the paint and my living expenses, very meagre on the whole, which we put into them.”