What Remains of the Body in A Mortician’s Tale

When we buried my grandmother in May, the first thing I saw when walking into the funeral parlor was something wrong.

When we buried my grandmother in May, the first thing I saw when walking into the funeral parlor was something wrong.

I hadn’t seen her in her last couple months—not in the hospital after her initial collapse, or the hospice where she was slowly worn down by the metastatic lung cancer—but my brother had. Even then we sat together in the front row, a few feet from the casket whispering to each other, trying to figure out what was wrong. Was it that they had put her in a dress? A thing we’d never seen her wear for as long as either of us had been alive. Was it a strange lighting they’d placed her underneath that colored her strangely in the frame left by the open casket?

No, it wasn’t either. Someone had painted her skin an artificial orange. She was tan in a way that never could have been. Her make-up was applied thickly where she’d normally have none. Maybe worst of all, though, they had taken away her glasses.

My brother and I were forced to accept that she was gone by being confronted with a version of her that could never have existed while she was alive.

Still, a thing I couldn’t shake was how she was made to look like that for someone. For however much of the modern Western language we use in talking about the dead, “their wishes” and how we can “respect” them, the result of these experiences and narratives in mourning are ultimately performative.

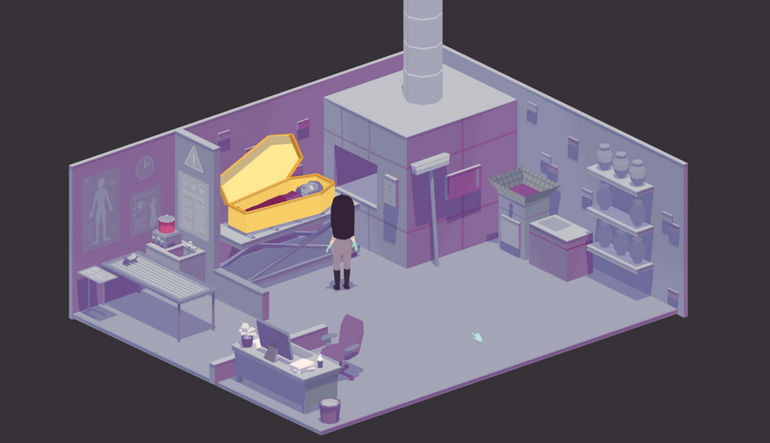

For the recent video game A Mortician’s Tale, we see just the level of production that goes into these performances. There’s a mechanical process here to mourning as Charlie, a recent graduate from mortuary school, starts her job as the funeral director at a mom-and-pop funeral home preparing bodies.

Preparing a person for an open casket funeral, one like my grandmother’s, starts with washing the body. From there you shave their body, their face. Massage the rigor mortis across their body and moisturize their chest. You place eyelid caps over their eyes and glue the eye lids closed. You shape their lips with cotton balls and sew the mouth closed. Cut open direct access to an artery into which you attach piping which connects to a formaldehyde machine that will be pumped through the body. Massage the arms and the chest to help ease the fluid’s passage. You’ll hear the purring of the motorized formaldehyde pump, too. Once that’s done, you sew the wound shut. From there you’ll need to drain the remaining fluids inside the organs and this…is all a lot.

For a closed casket, all Charlie has to do is wash the person. For cremation, it’s removing the person’s jewelry, placing a metal tag in the casket to identify the remains and running the bones that come out from the furnace through a machine that grinds them into dust. By translating how a body’s prepared for a funeral to the mundane physical action of clicking and dragging a mouse cursor across a computer screen, we understand that handling the dead isn’t just normal but often a process.

A mortician cuts, glues, pumps fluids to create the illusion that the person lost is here just long enough to say goodbye. There are moments in A Mortician’s Tale where Charlie visits the families for the wake. She pays respect to the deceased and hangs back, listening to the conversations around the room. You hear people making plans or talking about what show they’re planning to binge next. But then there’s a woman standing alone in a corner, saying, “She would have hated this music. She never wanted her funeral to be sad.” Across the room, in front of the food platter, two people in conversation talk about how the deceased would have liked this and that “She’d like that we’d all be here talking.”

In one room, two people see the same wake and try to think about the situation through the one they lost, ending up at opposite conclusions. They try to think about the wake as their loved one would have, what they would have wanted and would have hated. There’s no tangible point in the funeral aligning with the dead’s expectations because what matters is that they can stay with the memory of her for just a little bit longer.

Funerals in this way almost act like protective or communal domes—these little shelters where we cut ourselves off from the outside world so we can exist together under the weight of their memory. The style of a funeral is just set-dressing, and by adhering to “what they wanted,” we see that funeral parlor, this space of mourning, as an extension of them. Right before Charlie receives a body in A Mortician’s Tale, her boss doesn’t just tell her whether she’s preparing an open or closed casket but cc’s the email exchanges she has with the families. You can see in the family’s own words how they want their loved ones to be treated, get glimpses on who the ones they lost were, and maybe, more importantly, understand that the dead you work on mean something to someone.

There’s a moment, though, in A Mortician’s Tale where you embalm a young man. He’d killed himself and, before he died, left behind a will wishing to be cremated. He never had that will signed on by with an attorney and so when it comes time for his funeral, his parents go another way and ask for an open casket funeral. This moment is meant to feel uneasy. Your boss even gives you the option to turn it down and have another mortician handle it for you. If Charlie does it and goes to pay her respects, no one there really seems to care if the casket was open or closed. They’re just grieving.

There’s the sense here that maybe the wrong people are constructing this scene. That the parents didn’t care for their son in the way he needed them to and, in his death, aren’t creating the type of goodbye the people in his life needed. Still, those people still say goodbye.

At my grandmother’s funeral, on the opposite side of the parlor, facing away from the casket, was a projector. My mom and her sisters spent the days before the funeral, clearing through my grandmother’s apartment. They picked through shoe boxes and drawers for old polaroids that they turned into a slideshow. There were lots of photos of her holding me and my cousins as babies. Her standing at her children’s weddings and one where in her twenties, she posed with her sisters dressed in their bathing suits in the middle of a snowstorm. My mom and her sisters spent the funeral back there, facing away from the body and lost in these rotating pictures. They’d found their own way to mourn because, after all, the body is just a prop and there are more ways to inter a person than just into the soil.