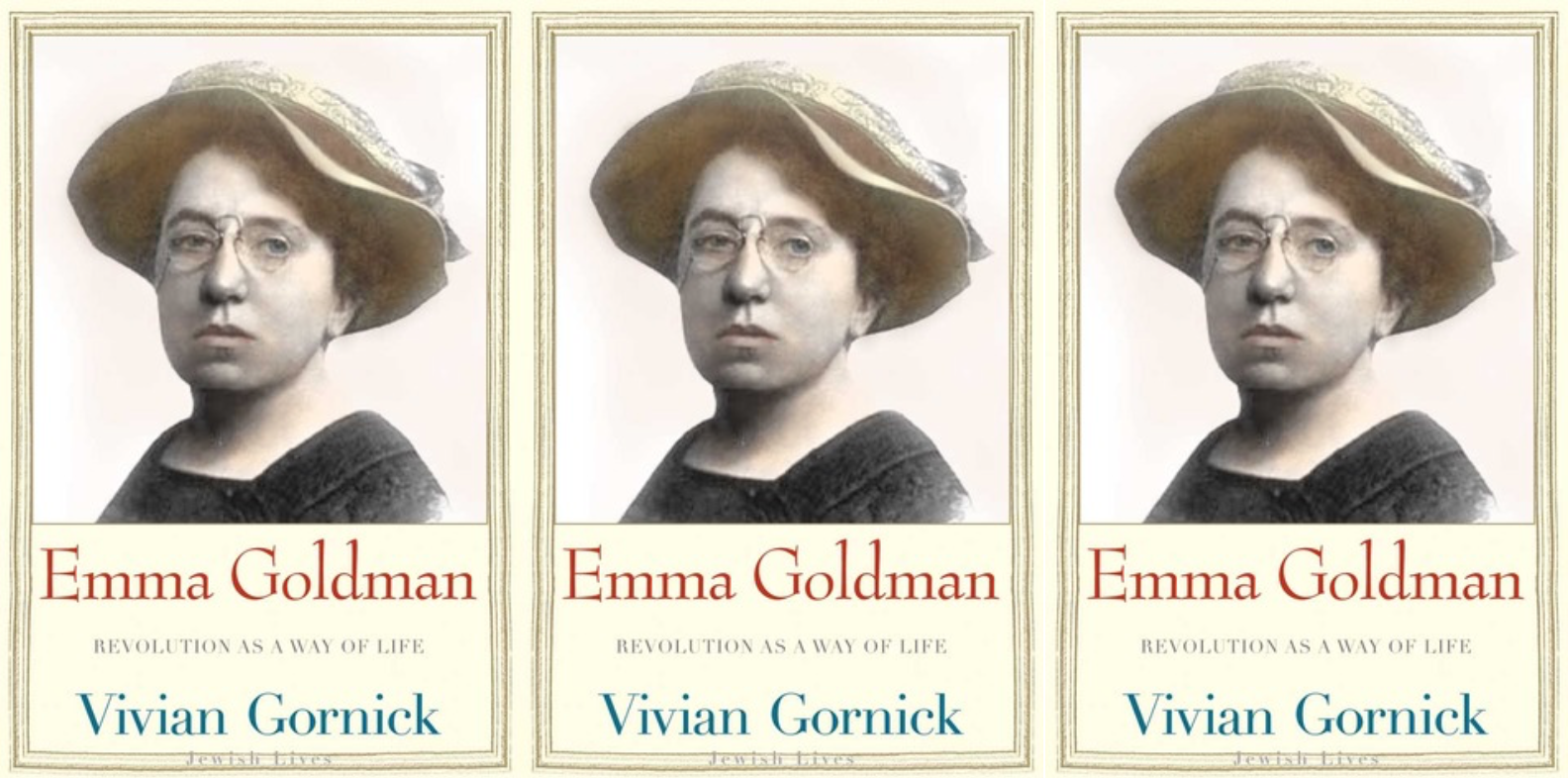

Women In Trouble: Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman: Revolution as a Way of Life

Vivian Gornick

Yale University Press, September 2011 (Part of the “Jewish Lives” series of interpretative biography)

160 pages

$25.00

In a new regular series, Anne Gray Fischer reviews books by or about “women in trouble.”

Last month, when the city’s crackdown on Occupy Boston was imminent, a wave of exuberant rebellion swept through the camp: amid the thickening police presence, protesters threw a dance party, pounding drums and moving their bodies in ecstatic celebration of their waning freedom. The furious, creative spirit of anarchist Emma Goldman—who famously, if apocryphally, declared, “If I can’t dance, I’m not coming to your revolution”—came alive that night.

Emma Goldman: Revolution as a Way of Life, by Vivian Gornick, is a lean and searching biography of the anarchist who defied the authority of both state and industry with a flamboyant rage that, a century later, remains bracingly relevant and still, perhaps, ahead of its time.

In this lyric meditation on Emma Goldman, Gornick is absorbed with the question of rebelliousness: namely, what sustains the rebel flame in those she calls “born refuseniks”? And how does the enduring thirst for “permanent revolution” manifest in the rebels’ private lives? Though J. Edgar Hoover deemed Goldman “the most dangerous woman in America,” in Gornick’s hands, Goldman is presented as a melancholic and melodramatic exile who “never came in from the cold” of the revolutionary’s peripatetic and lonely life, who could only access her own emotions in a posture that was “most useful to the Cause,” and who felt “nowhere at home” long before she was banished from her adopted homeland in the United States.

Anarchism at the turn of the twentieth century—the anarchism that drew thousands of working people to daily lectures and rallies worldwide; provoked the assassination of six heads of states; and circulated dozens of periodicals to thousands of subscribers in America—was an uneasy marriage of Marxist communalism and modernist individualism that aimed to achieve unbounded personal expression in a leaderless, cooperative society. Like many of her fellow radicals, Goldman, anarchist and individualist with equal fervor, fought against institutionalized authority’s “small humiliations that ate into the soul,” and avenged private hurt with outsize collective action. In a lovely reflection of this tension between the collective and individual that is marbled throughout anarchism, Gornick mingles nuanced insights into Goldman’s personal life with smart, if spare, historical sketches of Goldman’s milieu. Despite Gornick’s deeply psychological portrait of her subject, she keeps the reader satisfyingly aware of the social and political history in which Goldman was embedded. Particularly well illustrated is New York’s Lower East Side, where Emma and her notorious comrades “swam like fish in the sea…exerting an influence disproportionate to their numbers.”

While Gornick persuasively argues that Goldman was a uniquely indefatigable radical, she was also “supremely well met” by her time: politically charged years when “a great refusal was filling the air,” and ordinary citizens believed the coming revolution was “a universal certainty.” Gornick’s subdued prose is a welcome foil to what she rightly calls Goldman’s “high-flown rhetoric,” and her biography is a fine primer into “the despair and the excitement of revolt”—for the budding anarchist, the seasoned activist, and the armchair occupier alike.