Writing Trauma and Tarfia Faizullah’s Registers of Illuminated Villages

Two adjacent poems in Tarfia Faizullah’s new collection Registers of Illuminated Villages (Graywolf Press, 2018) reckon with the ways in which others—readers, peers, and perhaps mentors—respond to and even challenge the traumatic subjects about which a poet writes; in this case, the subject is a sister’s childhood death in a car accident the speaker survived. The first poem, “Great Material,” features a “conference / well-wisher” who swoons over the personal history. “What great material,” they say, adding, “Can’t wait to read that poem.” This all-too-familiar response risks reframing a trauma as mere fodder for writing. More than once, someone, upon hearing about one of my own great hurts, has responded by saying something to the effect of “Look on the bright side—at least you have something about which to write.” Let me assure you, however, that I’ve never thought, I’m so glad to have lived through this trauma/lost this person/experienced this violence because I got a book out of it. More often than not, I write poems in spite of those traumas and, sometimes, I even write about them. Whether I want to write about them isn’t relevant, as my poems find their way back into them no matter my starting point, no matter my desire to avoid the subject altogether.

Two adjacent poems in Tarfia Faizullah’s new collection Registers of Illuminated Villages (Graywolf Press, 2018) reckon with the ways in which others—readers, peers, and perhaps mentors—respond to and even challenge the traumatic subjects about which a poet writes; in this case, the subject is a sister’s childhood death in a car accident the speaker survived. The first poem, “Great Material,” features a “conference / well-wisher” who swoons over the personal history. “What great material,” they say, adding, “Can’t wait to read that poem.” This all-too-familiar response risks reframing a trauma as mere fodder for writing. More than once, someone, upon hearing about one of my own great hurts, has responded by saying something to the effect of “Look on the bright side—at least you have something about which to write.” Let me assure you, however, that I’ve never thought, I’m so glad to have lived through this trauma/lost this person/experienced this violence because I got a book out of it. More often than not, I write poems in spite of those traumas and, sometimes, I even write about them. Whether I want to write about them isn’t relevant, as my poems find their way back into them no matter my starting point, no matter my desire to avoid the subject altogether.

Faizullah writes about this sometimes harrowing and exhausting compulsion to write about a trauma or grief in “You Ask Why Write About It Again,” a defense against an unidentified person who’s questioned the reasoning, maybe even the efficacy, of writing once again about the sister’s death:

The hand

pressed hard against the pillow

does not want

to be the hand that lifts the pen again

to write the word sister

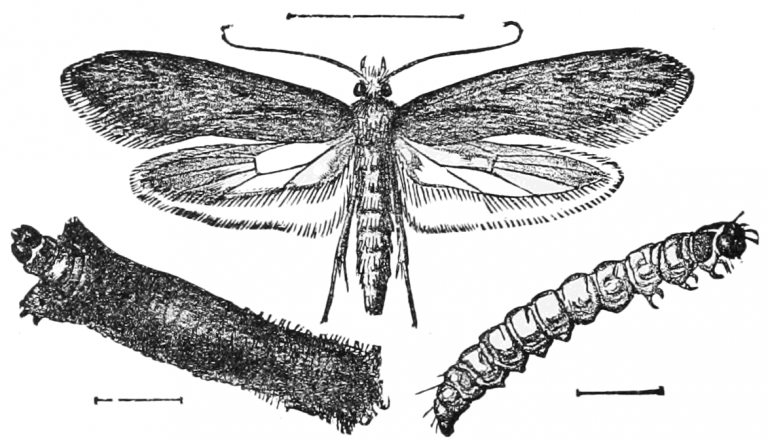

It seems to take all of the poet’s emotional (and maybe even physical) strength to write about the sister, and yet she cannot not write about her. By the end of this lushly imagistic and fraught poem, Faizullah demands that we “Praise / the ailanthus moth spinning / its coarse silk” for “it cannot stop, it must not,” just as the poet herself cannot—must not—stop writing.

Write your obsessions, many practitioners intone as general writing advice. Critics of subject matter, however, abound. A recent inflammatory review of Natalie Eilbert’s Indictus (Noemi Press, 2018), a book which “re-imagines various creation myths to bear the invisible and unsaid assaults of women” in order to reconstitute “notions of patriarchal power into a genre that can be demolished and set again,” is only one example of the kind of “criticism” that takes to task a poet’s subject matter in relationship to the autobiographical experience; the reviewer Sarah V. Schweig writes that the book’s notes section:

tends to literalize her poetry, pigeonholing it as belonging to the genre of marketable women’s poetry on sexual assault, narrowing its universalized moments into a subgenre, moving from the literary to the literal, offering itself up as catharsis for a particular group of women sexually assaulted by men.

This criticism absurdly suggests that a poet’s autobiographical ownership over their traumatic subject matter somehow makes the writing less artful and, therefore, allows these poems to only be appreciated by those who can “relate” to the subject matter because of and through their own personal histories of sexual assault, a claim which, among other offenses, dangerously conflates all (female) survivors of sexual assault and equates sexual assault survivors into a needy, exclusive marketing niche. Nevermind the fact that many sexual assault survivors statistically don’t report or publicly claim their experiences of sexual assault for fear of being shamed or not believed. Eilbert may have insisted upon her autobiographically ownership over the material in order to set a precedent for other survivors to do the same or she may have done it for some other, personal reason, which is neither here nor there when it comes to the poems’ artfulness and power. Schweig’s review likewise seems to dismiss the readers’ autonomous capacities for empathy and imagination, as if a reader couldn’t possibly engage with the subject matter without having experienced sexual assault—but only because of the poet’s claim to autobiographical trauma; the reviewer seems to suggest that, without the poet’s claim, others who have not survived assault could extrapolate and make metaphor of sexual assault so as to make it “meaningful” to them, as if making sexual assault only figurative isn’t an insult to its survivors, as if the book has to make comfortable those who haven’t experienced a similar trauma. (One can almost hear the same reviewer complaining about agency over the subject matter had the poet not claimed the trauma autobiographical, but I digress.)

Among some critics and readers, there floats the notion that making autobiographical claims over the trauma about which one writes is merely a simplified “political” gesture of unexamined victimhood—as with Schweig, who bemoans that Eilbert’s book only sustains “a previously agreed-upon narrative where men are bad in virtue of being men and women are good (or even pure) in virtue of being women”—but that’s often not the case. This is perhaps tied to the popular (misogynist) critiques of confessional poetry being “whiny” or “loud” or “shrill.” Regardless, when the critique is directed at subject matter from the poet’s personal history—a trauma, for instance—or immediately relevant to that personal history, it risks undermining the poet-as-person’s autonomy and agency, not only in their poems, but also their lives, while also perhaps subjecting the poets to the further trauma of erasure and silence.

A reader’s determination that one should or shouldn’t write about one’s own experiences, especially those traumas that inflame one’s past, feels like an unforgivable textual violence, one that deposes the poet from authorship over their own narrative. While some critics might feel comfortable telling Natalie Eilbert she shouldn’t reveal her personal history with her subject matter—in this case, sexual assault—or ask Tarfia Faizullah why she has written about a sister’s death more than once, it’s hard to imagine critics complaining about Frank Bidart writing about his toxic relationships with his parents or asking Gregory Orr why he has written about the shooting accident that killed his brother.