Two Views of Revision: Elizabeth Bishop and May Swenson

Consumers of art are usually endlessly fascinated with the evolution of a particular piece. We eagerly attend museum exhibits showing a great artist’s sketches or studies that resulted in an iconic piece; we use technology to see aborted attempts at images that an artist painted over in the effort to get things just right. Literary biographers luxuriate in a writer’s saved drafts: How did a poem or a story come to exist as a masterpiece?

Consumers of art are usually endlessly fascinated with the evolution of a particular piece. We eagerly attend museum exhibits showing a great artist’s sketches or studies that resulted in an iconic piece; we use technology to see aborted attempts at images that an artist painted over in the effort to get things just right. Literary biographers luxuriate in a writer’s saved drafts: How did a poem or a story come to exist as a masterpiece?

In his biography of Elizabeth Bishop, Brett C. Millier devotes a number of pages to Bishop’s brilliant villanelle, “One Art.” The drafts show a clear, laborious progression. In its earliest forms, it exists as prose notes by Bishop; she knows she wants to write it as a villanelle, but she initially just sketches in ideas she has for themes and a few half-hearted attempts at beginning: “This is by way of introduction,” goes draft number one. “I am such a / fantastic lly good at losing things / I think everyone shd. profit from my experiences.” The draft goes on just like this, not yet in the form that Bishop knew she wanted, not yet making any attempts at musicality, and lurching around good-naturedly, trying to stumble upon a tone or an image. In the margins of this typed draft are handwritten notes, where Bishop brainstorms possible rhymes. By the second draft, Bishop has wrangled her thoughts into the villanelle form, and she’s landed on one of the poem’s repeated lines: “The art of losing isn’t hard to master.” But It’s not until the poem’s fifth draft that the word “disaster,” the rhyming pair in the refrain, is discovered.

In the poem’s eleventh version, Bishop hits upon a version of her last couplet, that famous “the art of losing’s not too hard to master / though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.” This is the moment that makes the poem what it is, the speaker’s composure cracking open and belying the breezy acceptance of loss that has come before. It’s the equivalent of Leonardo da Vinci leaving the Mona Lisa’s face blank at the mouth until he’d painted her eleven times. Still, Bishop worked through (occasionally with the help of Frank Bidart) to seventeen drafts in total and, in each one, improved, clarified, became more precise, became more energetic.

But there are also cases where a writer’s drafts don’t show the same clear progress as “One Art.” May Swenson’s famous poem “Question” reminds us that drafts can represent successful pieces on their own; they are less an evolution and more of a parallel track. If Bishop’s poem shows a clear tightening and precision and a shedding of awkwardness into maturity, Swenson’s drafts show us that sometimes an artist simply makes a choice to fit a particular aesthetic preference or vision.

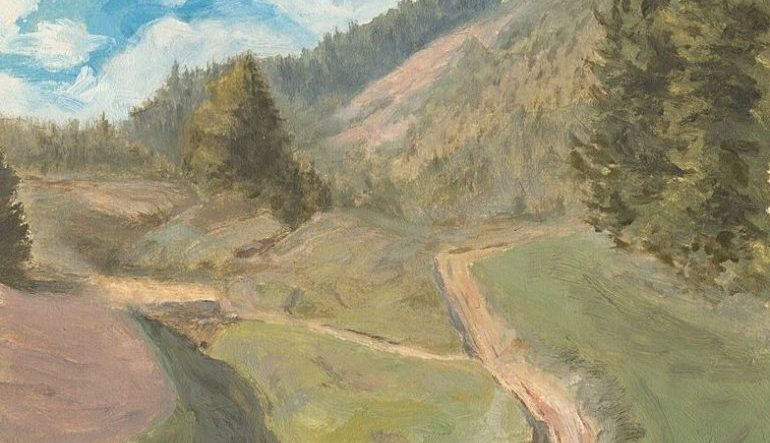

The finished version of “Question” is twenty-one short lines long, with no punctuation until a final, arresting question mark. It’s got a visceral rhythm, like a horse galloping that perfectly calls to mind the image that Swenson wants to consider—the body as animal, tearing through the landscape:

Body my house

my horse my hound

what will I do

when you are fallen

The poem is so controlled and spare and assertive that it’s a shock to encounter Swenson’s early drafts, where the poem is over fifty lines long, each line roughly ten beats—exponentially longer than what Swenson eventually honed them down to. Much of what Swenson is doing is a kind of freestyling of both music and ideas. An early draft’s first line, for example, captures the same galloping motion, many of the same nouns, and the same ideas of the final version, but with an excess of idea: “Oh body my house my horse my prick-eared hound / when you are lame then blurred then fallen.” Much of what makes the final version effective is present here; one is not clearly more evolved than another. It’s simply a matter of aesthetic choice.

It’s also true that to get the spareness of the final version of “Question,” Swenson had to jettison a lot of very beautiful writing. Most of the early draft of “Question” unspools the metaphor of body as a type of large animal, vital and hunting, with “love” as the prize. Swenson describes the animal’s “smiling sleep, flung before the fire,” its “frosty forelock and drooping back.” It carries the “lovekill home wet-jawed” and ends in “the mind-unwinding ground and the heart-departed dust.” Swenson was unafraid to lovekill her darlings, though, depending on the reader, we might mourn what was left behind. What matters is that Swenson clearly believed she was overwriting and carved away at the block of text that early drafts show us until she found something sleek and minimal.

Just as the fan of a movie might geek out over the director’s cut, or a music fan eagerly seek out demos of a favorite song or album, readers who admire a writer can benefit from biographies or articles that take readers through drafts. They remind us that revision is only sometimes about the uphill climb toward the ideal manifestation of a piece—it can also be about decisively making a choice in the aesthetic fork in the road.