A Novel of Mania: THE TIME OF MIRACLES by Borislav Pekić

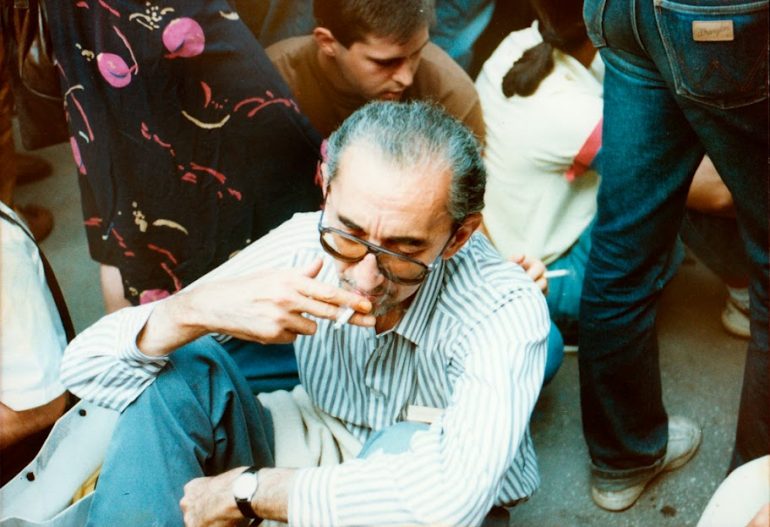

Borislav Pekić (1930-1992) was born in Montenegro and spent his youth in Belgrade. He was first arrested at the age of eleven for demonstrating against Nazi Germany. At eighteen years old, he was sentenced to fifteen years of hard labor for political activity (including the theft of typewriters). He served five years of his sentence and contracted tuberculosis while imprisoned. His only reading material was a donated bible, his only paper was toilet tissue, and his only pens were the teeth of a comb. Following his release, he published Vreme čuda in 1965, which was later translated from the Serbo-Croatian original to English by Lovett F. Edwards as The Time of Miracles. This book was the first of over thirty works of fiction and nonfiction, some two dozen plays, and more than twenty screenplays written by Pekić.

The Time of Miracles satirizes the fervent communist convictions of Pekić’s time, but it does so through the lens of the Christian gospel. It’s an example of what Barry Schwabsky calls a novel of mania, “in which the protagonist clings so strongly to his illusion that he never sees through it.” The protagonist in Pekić’s book is Judas Iscariot, the disciple who most avidly believed in Jesus of Nazareth’s status as the messiah.

Judas is invariably reviled in Christian literature as the one who ultimately betrayed Jesus, but Pekić casts his Judas differently. It is Judas who has memorized the prophecies and who dictates which miracles are to be performed; he approaches his role as disciple with a greedy, violent intensity. He’s a remarkable, ambivalent figure who casts a haunting shadow over Jesus’ miracles.

The first half of the book, “The Time of Miracles,” is a retelling of the gospel from the point of view of the recipients of Jesus’ blessings. While the lens of the four canonical gospels remains fixed upon Jesus during the three years before his death, Pekić takes six of the miracles—the transformation of water into wine at Cana; curing the blind, the delusional, and the leprous; restoring the virginity of whores, and raising the dead Lazarus to life—and refashions each from the perspective of the recipients. The healed, saved and cured aren’t nearly as grateful as their redeemer may have intended. In fact, for the most part, the infirm and sinful were perfectly content to live their lives as they were. Pekić’s Mary Magdalene explains, “The truth is, we were whoring on a grand scale and as the Book of Genesis says, we were happy earning our daily bread by the sweat of our own bodies. We weren’t in anybody’s way till your terrible companions came along.”

Disability scholars will be interested in the vivid, joyous portrayal of the lives of the unhealed. For example, Pekić writes of two men whose “exemplary friendship” is composed of mutually exclusive visions of the world around them. These are the same two who are said in the Gospel of Matthew to be possessed by devils. They’re known in The Time of Miracles as Legion and Ananias, and, “though they had to occupy the same territory at the same time and make use of the same facts, the worlds of Ananias and Legion were very different, contradictory and inconsistent.” Yet between the two, there is a “crazy tolerance,” broken only when Jesus heals them of their delusions. “The world now appeared desolate, worn, deserted. It looked like a picture from which the rain has washed the colors, like an event which nature has deprived of significance. Every scent had evaporated, every sound had been stifled, every movement turned to stone.” When the two learn that they now share the same reality, they despair, ultimately killing each other with the very chain that bound them together for so many years.

Jesus himself is portrayed as a gentle, almost negligible, figure in these stories, someone used by others for political gain. In the second half of the book, “The Time of Dying,” Jesus’ story is told from the perspective of Judas. He says, “To make sure not a single letter of the prophecy would be unfulfilled or overlooked, I took notes in Aramaic in the treasurer’s account books, day after day, hour after hour…” Judas is a stickler, a scholar, and a major annoyance for his cohort. He’s the one who propels the disciples onward to Jerusalem, the one who grieves the most about what must take place there. Literary efforts to redeem Judas’ reputation aren’t uncommon; some of the great writers of the 20th century have taken on the task, including Jorge Luis Borges, Nikos Kazantzakis, and Mikhail Bulgakov. But there’s something about Pekić’s novel that’s especially relevant in the present day. The Time of Miracles offers insight into the limitations of uncritical belief and the unintended consequences of well-intended actions. It’s a mirror for our time.

Verso Books reissued Pekić’s second novel Houses, translated by Bernard Johnson, in 2016, but most of his books remain untranslated. One must hope that this will change, for there’s a great deal that modern readers can learn from the observations of those who’ve lived through times of swift political change, especially when those observations are written as pointedly as those of Pekić.