Victory is Hers! Three Contest-Winning Chapbooks by Women

This month, I read three award-winning chapbooks—which happen all to have been written by women. Each chapbook is quite different in terms of subject-matter, but it’s they all have their a central theme holding the pieces within together. [Editor’s Note: If you’re looking for a contest for your own work, the Ploughshares 2017 Emerging Writer’s Contest opens on Wednesday!]

This month, I read three award-winning chapbooks—which happen all to have been written by women. Each chapbook is quite different in terms of subject-matter, but it’s they all have their a central theme holding the pieces within together. [Editor’s Note: If you’re looking for a contest for your own work, the Ploughshares 2017 Emerging Writer’s Contest opens on Wednesday!]

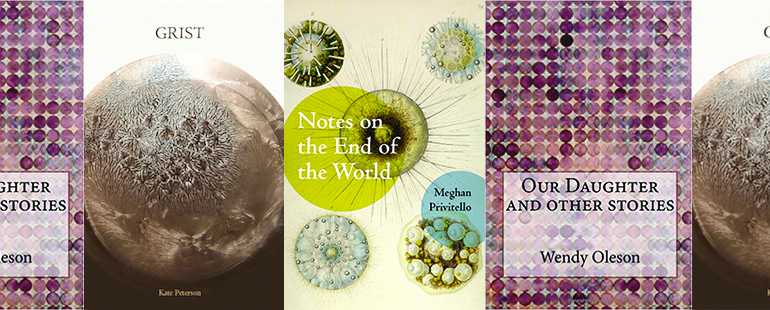

Notes on the End of the World

Meghan Privitello

Black Lawrence Press, 2016

Meghan Privitello won the Spring 2015 Black River Chapbook Competition for her Notes on the End of the World. Black Lawrence Press runs this competition; it accepts entries in both short fiction and poetry and has spring and fall entry periods. This year, the spring competition will open on April 1 and run through May 1.

This chapbook begins and ends with a poem bearing the same name as the book’s title, and the poems in between are each titled for a day leading up to the apocalypse, numbered Day 1, Day 2, and so on. More expected end-of-the-world motifs open the collection: worldwide over-corporatization, bees dying, flocks of birds dropping dead, and widespread pollution. The beauty of nature persists in the face of technology’s disruption.

There’s the idea of a storm planted in the first poem that subtly weaves its way through the rest of the book, yet at the same time, whether the world is truly ending or not is up for debate at one point: in “Day 18,” the speaker says, “Doctors ask if you come from a sick family, / try to convince you that fear is biological.” What if the storm is only a personification of this fear? In the America of 2017, an idea like this feels almost too real in its uncertainty.

Much of the speaker’s emotional complexities surrounding the impending doom of the planet are given depth through small considerations of optimism: “Passion was most fresh / when temporary” the speaker notes in “Day 4,” and then, “This is not a curse… / I can finally give up / figuring out who I am” in “Day 8. ” There is also hope: “A storm is dividing the sky into sections like an envelope. / I want to lick it and seal it shut” in “Day 5,” and pessimism: “Somehow, we’ve all been given the same fate, / which means our lives are ordinary” in “Day 7.”

Grist

Kate Peterson

Floating Bridge Press, 2016

Kate Peterson won the 2016 Floating Bridge Press chapbook competition for Grist. The contest is currently open and accepting submissions from Washington state poets through March 15. Floating Bridge Press has been running this competition since 1995.

The body takes center stage in Peterson’s chapbook, which is divided into four parts; the first, Osteology, takes place mostly in a hospital. The speaker’s physical identification with her place in the world continues over into the next section, Embryology, which concerns poems that surround pregnancy and birth.

Peterson is at her best when allowing her speaker to muse on a body’s perceived abnormalities in a way that invites a reader in to understand them as differences instead. She calls a womb that recently miscarried a “red wet grave” in “Upon Finding Out I Miscarried Our Child While Flying Over Lake Michigan.” The speaker is most concerned with how to tell her partner, wishing that it could be as easy as “when I lost my favorite ring and you told me it couldn’t / have just disappeared.”

The chapbook’s final two sections, Histology and The Articulations, focus on horses and a failed relationship while still concerning the body—the spiritual relationship between human and horse must be built on one of physicality, readers learn in “Equestrian.” In the final section, a failed relationship takes center stage, but a focus on the body is still apparent.

Our Daughter and Other Stories

Wendy Oleson

Map Literary, 2017

Wendy Oleson’s Our Daughter and Other Stories won the Rachel Wetzsteon Prize, the award given to an annual contest run out of William Paterson University’s Map Literary. The prize’s genre rotates between poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and Oleson won for short fiction; the next competition will most likely be in nonfiction, as the previous winning chapbook was a work of poetry.

The title story in Oleson’s winning collection is also one of the shortest in the book. Its structure, categorization, and theme showcase what holds this collection together: its concise and varied forms that still feel full, its ability to skirt the line between realism and magical realism, and its theme of difficult, often familial, relationships, often focused on daughterhood. The “our” in the title represents all of the people who could be related to a daughter who are represented in the chap.

The opening story “How I Liked the Avocados” seems on the surface a mundane one, about the narrator’s surreptitious eating of avocados, but by the end of the work of flash, readers are aware of the reason the narrator is keeping the “you”’s identity a secret. Oleson’s collection bonds a daughter with her mother just before she vanishes from her life in “Bodies of Water”, a son with his mother just before the end of the world in “Record of a Farmhouse” (which, in the interest of disclosure, was, along with the title story, a finalist in last year’s flash fiction contest run by Gigantic Sequins, a journal for which I am the editor-in-chief), and a reluctant young lesbian narrator with her sad excuse for a human Uncle over a trip to a roller skating rink.