Joan Didion’s Hostile Acts of Observation

Joan Didion’s unique worldview—that laser-sharp analysis of everything from the California coastline to Doors frontman Jim Morrison to her own personal grief and loss—might have been formed the day she failed to make Phi Beta Kappa at the University of California at Berkeley.

We know Didion’s university career wasn’t a total loss. She won Vogue’s Prix de Paris writing contest, and moved to New York to work at Vogue. She wrote this article on self-respect for the magazine in 1961. Didion’s essay, written at the last minute when a lesser author failed to deliver copy on the same topic, begins by mourning her charmed childhood:

I lost the conviction that lights would always turn green for me, the pleasant certainty that those rather passive virtues which had won me approval as a child automatically guaranteed me not only Phi Beta Kappa keys but happiness, honour, and the love of a good man […] lost a certain touching faith in the totem power of good manners, clean hair, and proven competence on the Stanford-Binet scale. To such doubtful amulets had my self-respect been pinned, and I faced myself that day with the nonplussed wonder of someone who has come across a vampire and found no garlands of garlic at hand.

Put in more contemporary terms, Didion realized she was not a special snowflake. The world did not revolve around her and quite possibly never would. Perhaps, in view of this, she chose to spend the rest of her life writing about people and things she thought the world might actually revolve around.

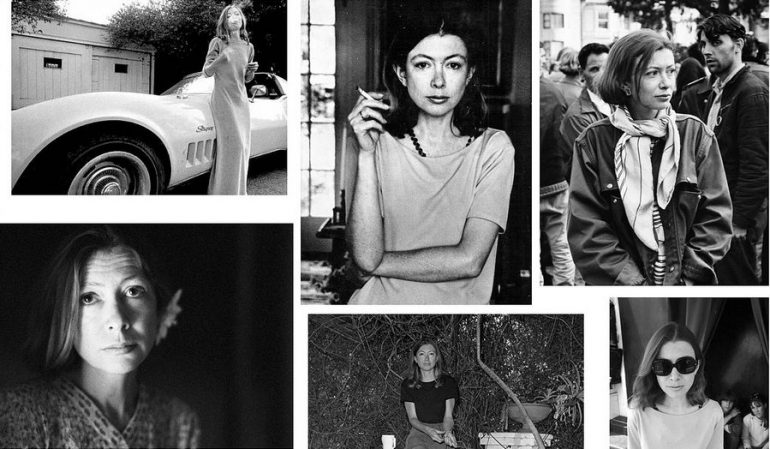

To do this she would seek out her flamboyant and topical subjects and then just watch and wait—observing everything but saying nothing. At times she compared herself to wallpaper. Other times she credited her petite frame for allowing her to pass through history unnoticed, but noticing. No matter what modern chaos she fixed her gaze upon, she always came away shaking her head, secure once again in the knowledge that the center truly does not hold, that nothing is as special as it seemed.

In the spring 1967, Didion famously found herself in Haight-Ashbury, a section of San Francisco regarded as the center of the counterculture. She immersed herself in the world of hippies, runaways, addicts, cops, musicians and small children playing with matches. She talks about the experience in the Netflix documentary “The Center Will Not Hold” now streaming on Netflix and directed by her nephew Griffin Dunne. She recalls the moment when she met a five year old girl wearing white lipstick who had just taken LSD. It’s a chilling image and Dunne asks her what went through her mind when she saw the child. The camera pulls in on Didion’s face just staring at him as if he had just asked her if the sun had come up that morning. She gestures extravagantly with one hand.

“Well, it was gold.” she said and paused for a moment “You live for moments like that, if you’re doing a piece. Good or bad.”

Watching at home, I gasped audibly, but of course, she was right. I also know she saw literary gold where others wanted to grab the little girl and make a run for it to the nearest emergency room or child protective services. That’s what separates Didion from mere mortals with a laptop and a literary dream. She waited for those golden moments and shared them without inserting herself into the story, without any overt judgment. Whether her readers were moved or repelled made no difference as long as they kept reading.

“She has a horror of disorder,” says a fellow traveler in the documentary. “That was a feature of her writing and her life.” In a 2015 article in The New Yorker Louis Menand wrote that it was hardly a surprise that Didion, a Goldwater Republican, found Haight-Ashbury ‘repugnant.’ “Her editors at the Post understood perfectly how she would react. They designed the cover before she handed in the piece.” However it was how she conveyed her distaste as the only appropriate response by just letting the scene unravel as it happened, piling one lurid first-person account on top of another until it’s almost impossible not to feel something.

Steve is troubled by a lot of things. He is 23, was raised in Virginia and has the idea that California is the beginning of the end. ‘I feel it’s insane,’ he says, and his voice drops. ‘This chick tells me there’s no meaning to life, but it doesn’t matter, we’ll just flow right out. There’ve been times I felt like packing up and taking off for the East Coast again. At least there I had a target. At least there you expect that it’s going to happen.’ He lights a cigarette for me and his hands shake. ‘Here you know it’s not going to.’

‘What is supposed to happen?’ I ask.

‘I don’t know. Something. Anything.’

Didion’s dislike of chaos and her admiration for Hemingway’s sentences (“They’re very direct sentences, smooth rivers, clear water over granite, no sinkholes,” she told an interviewer) made her the perfect observer for turbulent times. She went where ordinary readers would not go: to the lost children of Haight-Ashbury, the jungles of El Salvador, and clothes shopping with Manson family member Linda Kasabian. She is the perfect observer, standing on the outer fringes, looking fabulous, smoking a cigarette and watching—waiting for that one moment of gold—for good or bad that would compel readers hang on her every word. “She’s not like us,” Menand says. “She’s weird. That’s why we want to read her.”

“I’ve always gone around most of the day totally blank,” she told British Vogue in 1979.”I never even know what I think about a book unless I’m asked to review it. Then I sit down and laboriously find my way through to what I think about it.”

She thought about the women’s movement for The New York Times Book Review in 1972 and pored over scores of writings by movement leaders and distilled her distaste for the cacophony of ideas into what modern readers would consider a privileged rant against naive homemakers she came to feel were mired in trivia and avoiding serious sociopolitical issues:

It was a long way from Simone de Beauvoir’s grave and awesome recognition of woman’s role as ‘the Other’ to the notion that the first step in changing that role was Alix Kates Shulman’s marriage contract (‘wife strips beds, husband remakes them’) reproduced in Ms.; but it was toward just such trivialization that the women’s movement seemed to be heading.

Once Didion has an opinion, she wants it to be the reader’s opinion as well. “There’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space,” she said in a Regent’s address at Berkeley in 1976.

Perhaps not being elected to Phi Beta Kappa was the best thing that could have happened. Realizing that nobody would automatically deem her special, she sat down at her typewriter to show them that her worldview was special. In an interview with the Paris Review in 1977, she described writing as a hostile act: “It’s hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it,” she said. “Trying to impose your idea, your picture. It’s hostile to try to wrench around someone else’s mind that way. . . . The writer is always tricking the reader into listening to the dream.”