The Ploughshares Round-Down: Publishing Isn’t Dead

There’s an old joke in publishing about consultants, though it’s probably rooted in truth. A new executive hires a prestigious firm to spend months on an expensive deep dive, and they come back, excited, with one key insight: “You should publish more bestsellers, and fewer books that aren’t bestsellers.”

There’s an old joke in publishing about consultants, though it’s probably rooted in truth. A new executive hires a prestigious firm to spend months on an expensive deep dive, and they come back, excited, with one key insight: “You should publish more bestsellers, and fewer books that aren’t bestsellers.”

Why didn’t we think of that?

All of the biggest houses need bestsellers to make their annual numbers, and those numbers are big. How big? To pick a random comparison, HarperCollins generated about $1.4 billion in their last fiscal year. That’s “billion” with a “b.” That’s just a bit less than, for instance, The New York Times over their last fiscal year. And HarperCollins did it while generating a bit less in expenses.

How important are bestsellers to getting to that number? Last week, based on Bookscan sales data, it looks like Ina Garten’s new book generated about $2.5 million in physical book sales for her publisher in just seven days. That’s a big number, but it also requires an army of people in production, sales, distribution, marketing, editorial, and more.

Keep that in mind while reading the most talked-about article in book publishing from the last week–Matt Yglesias’s piece in Vox: “Amazon is doing the world a favor by crushing book publishers.” There have been plenty of articles in the past few years claiming publishing is dying, but this one is possibly the most popular one I’ve come across.

It’s also the only one where the author’s disillusionment is possibly entirely my fault.

What Went Down

Yglesias is one of the founders of Vox, itself a new, buzz-generating news and analysis website, and he’s well-known for his brilliant, snarky takedowns of common wisdom. In the article, he made a bunch of important—and highly debatable—points: Book publishers are giant, frequently foreign-owned, profit-obsessed conglomerates. Book publishers could be competing with Amazon, but simply lack the will and imagination. Amazon’s immense market share is being eyed every moment by competitors large and small, each of them putting money and smarts against Amazon’s strategies to gain more for themselves. Publishers are bad at editing and marketing, the only two value-adds they have left.

As with almost anything he writes, others rushed to contradict him. The New Republic pointed out that “a publisher’s list of books is in essence a risk pool,” with the advances making sure every ever author on the list gets some money, whether they succeed or not. An author avoiding this pool because she is sure she will succeed is like a person going without health insurance because she is sure she won’t get sick, but even riskier. Salon argued that publishers might not be so bad at capitalizing on our digital future, as revenues have been rising in the past few years. The Los Angeles Times worried that publishers protect and nurture young novelists, essayist, and poets—often at a loss–who might not be able to find any audience at all in a book publisher-free world.

Where I Come In

Part of me thinks Yglesias is just kidding. After all, you could go back and reread his piece swapping “magazine” for “book,” and the whole thing makes sense: There was a time when it was argued that all magazines and newspapers would fail–the thought being that writers with their own followings would abandon them for running their own websites. Not only has he not given up on magazines, he recently cofounded (a very good) one.

Perhaps his website, Vox.com, is much better at marketing and editing than book publishers are. Or it’s possible that the publisher—by which I mean me—of his one hardcover book did a terrible job.

About a decade ago, when I was an editor at Wiley, I chased after Matt because I was a big fan. At the time he was in his mid-20s and blogging for The American Prospect. He had written a few immensely popular pieces about the Iraq war, and I talked my team into writing him a pretty good sized check. Then I talked him into taking that check and writing a book.

He’s right that I did a terrible job of editing the book. Sure, I worked on it, maybe even making sentences and paragraphs and arguments sharper. The book itself landed somewhere between good and great in an intellectual vacuum. It wasn’t, however, what his readers were looking for. As you can tell from this piece, his fans like sweeping, counterintuitive arguments. They like his snark. They also like his fun asides about basketball, comics, philosophers, and obscure novelists. At the time he wrote the book, he had many jealous critics who said he could never write a serious, thoughtful book like their dry but important tomes. He showed them. As his editor, I could have applied the brakes at any moment, called him up, and told him to write a book closer to what his regular readers would adore, and I didn’t. I believed everyone when they said the serious book would sell better. I was too close to the material, and thought he was right about everything in the book. I figured that would be enough, and I was wrong.

I also did a terrible job of marketing Matt’s book. Sure, I wasn’t the marketer or the publicist for his book, but inside of a publishing house, the editor is the navigator, plotting the course (and depending on the imprint, actually steering the ship). Our promotion for the book amounted to a great cover, mailing books to all the usual suspects, and crossing our fingers. I think we also paid for part of a book party and for some blog ads, but those contributed exactly as much sales as you would think. Most of the outlets we were hoping for passed; Matt’s readers smiled and said, “Maybe in paperback.” We sold enough to be proud of, but not enough for Matt to eagerly write up a proposal for a new book. At no point did I thump the tub for bigger marketing outlays, work connections to get publicity we might otherwise have failed to get, or coordinate a marketing campaign that was clever and original. We hadn’t had the budget for that anyway.

I’ve gotten a lot wiser (often the hard way) about book publishing, so I hope my editing has gotten better. But his book was never one that was going to require an all-out marketing blitz like Nora Roberts, John Grisham, Ina Garten, or Bill O’Reilly. So the marketing that he’s seen up close is far from the best the industry has to offer.

All the Matt Yglesiases Actually Might Self-Publish

His experience–and the experience of some of his friends and family–isn’t actually relevant to the future of publishing. Much of book publishing is tremendously good at marketing. It’s just that most of the revenue and most of the marketing go towards books that will sell a gazillion copies. If self-publishing ends up pushing many of the people who write for Vox or TNR or even Ploughshares into profitably self-publishing (a scenario I still very much doubt), that isn’t going to destroy the publishing industry. The guys from Duck Dynasty and Dick Cheney and George R. R. Martin and J.K. Rowling still need publishers to do all kinds of work for them, and the publishers do a great job marketing their books.

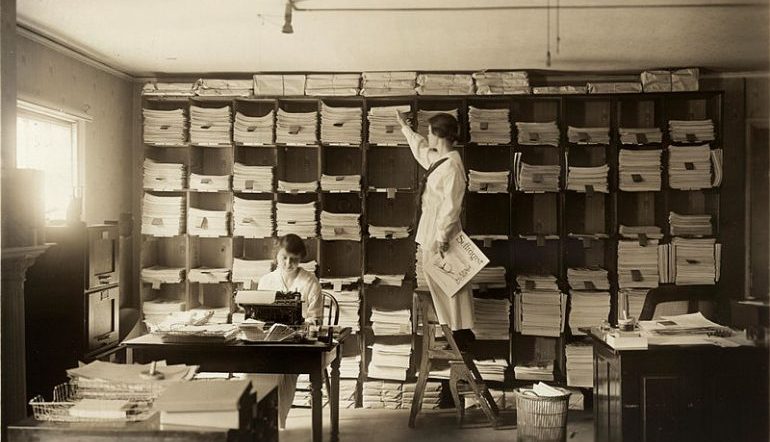

Of course, the editors working on those books will have to keep signing unknown authors in the hopes of finding the next J. K. Rowling. Most of those authors won’t live up to their potential, and I’m sure all of those will blame the publicity department of their publisher. Luckily, those publicists can take anything you throw at them, usually because they’re sitting behind a wall of books they need to mail out on behalf of the next book they’re pitching.