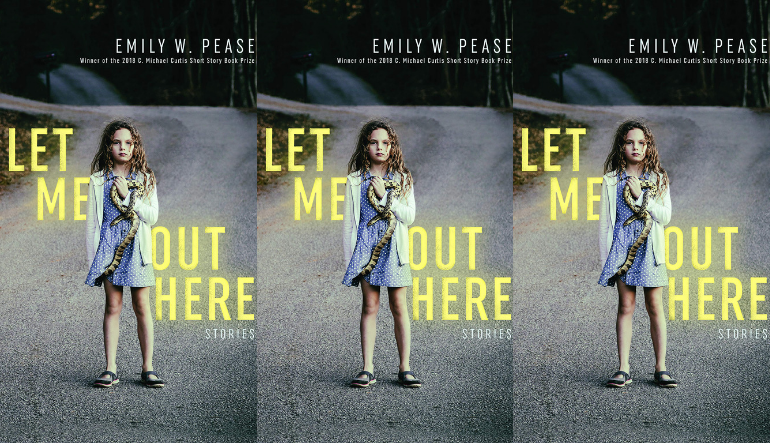

Let Me Out Here by Emily W. Pease

Let Me Out Here

Emily W. Pease

Hub City Press | March 19th, 2019

Amazon | Powell’s

If you’ve ever driven through the mountains of West Virginia in the snow at night and been afraid, you might recognize the feeling one gets from reading Let Me Out Here Emily Pease’s debut collection. Her stories are at times dizzying and dark with a hint of dread, but are also rich with texture, voice and a wild beauty. In an interview with her publisher, Hub City Press (Pease won its C. Michael Curtis Short Story Book Prize, which includes publication, for the collection) Pease said the South, to her, is “beautiful and memory-rich, with a layer of dark.” The same could be said about her stories, though the layer of dark within is thick and permeates the whole—like the heat on an August day in the South, nothing is left untouched by it.

The stories of Let Me Out Here, which is set in Tennesee, North Carolina, and West Virginia, range from flash fiction to nearly novella length. They seem classic, or weathered—as if they have withstood the test of time. They are often about God, death, and small apocalypses. Others focus on the strangeness of the mundane: birthday piñatas, shaving one’s legs for the first time, aging. A couple date back to the Vietnam War; some are modern. Cell phones, The Bachelor and Hannah Montana don’t seem out of place, even in these backwoods locales, places that seem to exist where time passes differently, or maybe hasn’t passed at all.

Pease’s collection opens with a story, “Submission,” that does a great job defining the collection. Its first sentence lets us in on who will inhabit these stories, these worlds: “We were the family you wanted to avoid, dumb pilgrims stumbling along the Fiery Gizzard Trail on a mission.” The more we read of the book, the more apt we are to agree, or not, depending on the company one likes to keep. The Coopers are country people who don’t believe in technology or doctors. They’re on a pilgrimage to a waterfall on the Fiery Gizzard trail with their sick baby who was born with low muscle tone. He’s having breathing problems. The baby gets worse as they get closer to the waterfall. To be a Cooper, the narrator says, you have to be “Brave enough to be in this world but not of this world.”

In another story, “The After-Life,” Pease earns the comparison to Ottessa Moshfegh that shows up on the back of the book (Pease is also compared to Mary Gaitskill and Kelly Link). The narrator, Judy, in this story bears some resemblance to the narrator of Moshfegh’s novel, Eileen. Judy makes one questionable decision after another, and the reader just follows along waiting to see what she will do next. Out of loneliness, she talks to a middle-aged cab driver, Bruce, on the hall phone of her dormitory. She calls herself Ruby. What had her life been like so far? “Picture a mouse at the back of a drawer.” She never deludes herself in thinking Bruce young or handsome as they talk on the phone. Instead, she seems comforted by who she imagines him to be: “I pictured him in a dingy kitchen with a buzzing refrigerator; I had him in a chair at his kitchen table with a Formica top, his spotted hands clutching a coffee mug. A widower, retired, with no one to talk to but me.”

The characters in these stories try in their own twisted ways to connect with or please others—a daughter does ecstasy with her father, a man takes a trip with a dangerous stranger to get his girlfriend a kitten, a mother gets too drunk at a family party. But they’re running from something, too. At the very least, they’re trying to escape the monotony of their daily lives.

In one of the highlights of the collection, “Primitive,” a young mother stuck at home all day gets bored and investigates the shed in her yard. It’s where her boyfriend, Donnie, keeps the poisonous snakes he handles at church. He’s a preacher and sees them as a “visible sign of faith.” This story uses Chekhov’s gun to maximum effect. Once we know the snakes are boxed up in the shed, we keep reading, just waiting for someone to get bit. And someone does.

It’s stories like this that make one think there aren’t nearly enough snake handling stories. There aren’t nearly enough books like Let Me Out Here either. Pease’s voice is powerful and exacting, funny and fierce—like Flannery O’Connor, but not too much like her. In “Primitive,” Donnie and the narrator talk about good and evil. “Life is hell on earth,” he likes to say to her. “But that just gives me hope!”