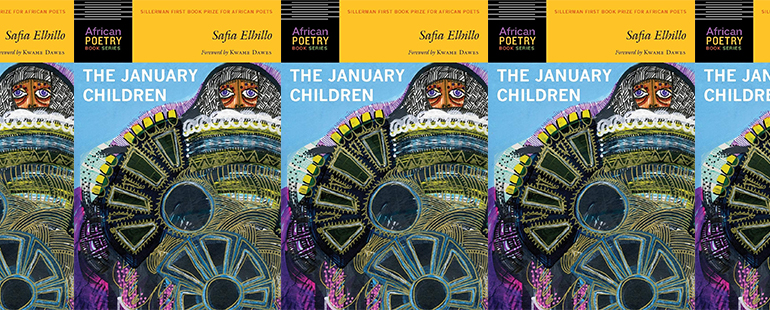

The Persona as a Portal in The January Children

Winner of the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets and the Arab American Book Award, writer Safia Elhillo’s debut full poetry collection, The January Children, is an auto-fictional work that constellates around questions of identity and home—questions that living legacies of colonization, war, immigration, and anti-Blackness complicate for the Sudanese American speaker. Elhillo contextualizes the book’s colonial history through three epigraphs: at the forefront, she defines the January Children as “the generation born in Sudan under British occupation, where children were assigned birth years by height, all given the birth date January 1.” (Sudan declared independence from Britain and Egypt in 1956.) She also quotes from the famous Syrian Lebanese poet Adonis’s poem “Quddās bi-lā qasd” (“Unintended Worship Ritual”): “How many centuries deep is your wound?”—a precursor to poems that contemplate the speaker’s visceral, bodily experience of nationalism and racism. In between these two epigraphs, she introduces the Arabic term of endearment “asmarani”:

أسمر : /as-mar/ adj. dark-skinned; brown-skinned

أسمرانی : /as-ma-ra-ni/ diminutive form of أسمر

The term asmarani—which hearkens back to Elhillo’s second chapbook, of that title—enters Elhillo’s poems from the love songs of the iconic Egyptian singer-heartthrob Abdelhalim Hafez (1929-1977) whose, according to the poem, “biopic containing lies about abdelhalim hafez,” “left behind two siblings & four / hundred thousand widows,” and “haunts the balcony /of every girl born brown & far away.” He recurringly addresses a lover as asmarani in his lyrics. Sometimes asmarani takes the form of a girl, and, as in “everything i know about abdelhalim hafez,” sometimes he “sings of his country as a beautiful girl / washing her hair in the canal.” The term holds resonance as a cultural, national, and relational descriptor. Over a series of imagined encounters with Abdelhalim, a central question for The January Children’s speaker becomes whether or not she, a Sudanese American woman, is among the women Abdelhalim addresses—if she “counts” as an asmarani. The construct of these imagined encounters seems to function as a vehicle that allows Elhillo to explore complex questions of identity—including nationhood, race (and Arab anti-Blackness), language, and hybrid identities—as well as the restorative potential of self-identification.

In The January Children (2017), both the historical figure of Abdelhalim Hafez and his personification seem to serve as an umbilical cord connecting the speaker to her heritage as she navigates the trauma of immigration. In the poem “call back for the position of abdelhalim hafez’s girl,” an interviewer asks, “when did you first hear abdelhalim.” The speaker replies, “after my mother’s first attempt at leaving my father we’d left Egypt for a pink house in / geneva.” When the interviewer repeats the question, the answer shifts. The speaker replies, “in my grandmother’s kitchen she knew all the words.” She also replies, “the first time i heard abdelhalim was when i moved to new york city & finally got rid of / my accent.” And she offers a fourth possibility: “the first time i heard abdelhalim hafez was when my mother moved back to egypt & cairo was / burning.” Although these responses present striking differences, I am more interested in their similarities—what they tell us in collage.

In tandem, we see that the speaker associates Abdelhalim Hafez with moments of diasporic trauma. She hears Abdelhalim Hafez “after my mother’s first attempt at leaving my father,” the word “attempt” here requiring border-crossing. She hears him during the violence of assimilation requiring the “rid of / my accent.” She hears him when she is separated from her mother by an ocean; her mother has moved to Cairo while “cairo was / burning.” As often as the speaker names Abdelhalim Hafez in the background of diasporic trauma, though, she also brings him to the forefront elsewhere in instances where she feels connected to her heritage. In all four of these instances, for example, the speaker associates Abdelhalim Hafez with a female family member: first, her mother; second, her grandmother; third, herself. Abdelhalim Hafez becomes an objective correlative for the intergenerational familial relationship between these three Sudanese women. The speaker is more explicit in “while being escorted from the abdelhalim hafez concert” when she admits, “it’s only that i’m west of everything i understand.” As a means of comfort, she turns to Abdelhalim Hafez’s music: “i know the words they help / when i go home east of everything i learned.” Here, “west of everything i understand” refers to Sudan, and “east of everything i learned” refers to the U.S. The historical figure of Abdelhalim Hafez, here and elsewhere in the collection, serves as the intermediary that the speaker seeks to make cognitive consonance of her hybrid identity.

In addition to appearing as a historical figure in Elhillo’s book, Abdelhalim is also a character in a series of about twenty persona poems that give the collection its narrative arc. In these poems, before Abdelhalim takes on the roles of “boyfriend” and “ex,” he first takes on the role of an interviewer while the speaker takes on the role of the interviewee, interviewing for the “position” of Abdelhalim Hafez’s “girl.” There is, of course, an allegorical power imbalance to unpack from these character roles; the persona of Abdelhalim not only underscores what we already know about him as a historical figure—that he is a cultural icon—but also imbues him with a sense of cultural authority. As the interviewer, he asks questions that serve as microaggressive authenticity checks. In “callback interview for the position of abdelhalim hafez’s girl,” he asks: “then you do think you’re the girl from the song”; “you know he didn’t mean that brown you know he didn’t mean black”; “what are you exactly are you arab or not are you black or not”; and “would you care to address the treatment of nubians in egypt & in the arab world at large.” (Although here the persona is ambiguous—the interviewer refers to Abdelhalim as “he,” suggesting that Abdelhalim is not the interviewer at all—the consistency elsewhere is strong enough that I wonder if “he” refers to the songs’ lyricist here.) In “final interview for the position of abdelhalim hafez’s girl,” he continues, “do you speak arabic”; “what brings you here today”; and “do you know the double meaning.” It seems notable that none of these questions end with question marks, as though the questions are perfunctory and the interviewer’s assessment already complete. Abdelhalim’s purpose is essentially to perform a gatekeeping role as the interviewer—he is the expert, interrogator, judge of qualifications, requester of character references (i.e. proof of social approval), and the ultimate decision-maker regarding whether the speaker is a suitable “asmarani.” This is synonymous with the assessment that his role is to decide whether or not she belongs.

Elhillo’s rhetorical decision to reimagine the historical Abdelhalim Hafez as an interviewer in these poems serves as a vehicle to establish and critique anti-Blackness in the Arab world. Integral to this argument is an understanding of Egypt’s cultural influence in Sudan as a result of its colonial history in the country. In “callback interview for the position of abdelhalim hafez’s girl,” the speaker explains her grandmother’s infatuation with Egyptian pop culture: “she knew all the words the story goes that / she was the fairest of her sisters & knew all the Egyptian films by heart could have fit / right in from what i’ve seen in pictures / … / she’d learned the accent the affected lilt.” In the memorization, the “affected lilt,” and the mention of light skin (“her sister Fatima would say / why because your face is white that’s just paint on a mud wall”), there is a kind of aspiration toward whiteness here—even though the cultural influencers are Arab. (Britain officially occupied Egypt until 1922. One hundred years later, orientalism remains alive and well.) At the same time, there is the sister’s (if problematic in its own right) critique of the grandmother’s internalized racism. In “abdelhalim hafez asks who the sudanese are,” the speaker describes the Sudanese as “Arabized Africans. Mostly from Nubian Tribes / Adopted Arab Culture and Language Self-Identified / [as] Arabs.” She notes the distinction between Sudanese racial self-identification and “Arab” identification of the Sudanese: “Arabs Consider Northern Sudanese Not / Arabs but Africans Aspiring to Change Their Race.” We see threads of colonialism and internalized racism—especially in the language, for example, of “Africans Aspiring to Change Their Race”—and differing racial identifications in the power dynamic between interviewer and interviewee, in the content of several of the interview questions that Abdelhalim asks. “You know he didn’t mean that brown you know he didn’t mean black,” for example, from “callback interview for the position of abdelhalim hafez’s girl), and even the problematic premise that Abdelhalim Hafez—an Arab Egyptian pop star—might serve as an icon for and authority on Sudanese culture in the first place.

We see threads of colonialism and internalized racism in the structural power imbalance between interviewer and interviewee as well as in the content of several of the interview questions that Abdelhalim asks. (“You know he didn’t mean that brown you know he didn’t mean black,” the interviewer insists, for example, in “callback interview for the position of abdelhalim hafez’s girl.) We also see these threads in the problematic premise that Abdelhalim Hafez—an Arab Egyptian pop star—might serve as an icon for and authority on Sudanese culture in the first place.

I am most interested, for these reasons, in the moments in which the speaker veers off the script of interviewee filling out questionnaire, interviewee providing references of social approval, and interviewee defending her suitability with acceptable evidence. I’m interested in moments when the speaker answers the interviewer’s questions slant, as in “callback interview for the position of abdelhalim hafez’s girl,” forcing the interviewer to ask the question again or admit “i don’t follow.” I’m interested in the speaker’s pushback. In “late-night phone call with abdelhalim hafez,” the speaker identifies moments of authenticity checking by not only reminding Abdelhalim, “you don’t have to translate,” but also pointing out that “you know i still speak it”—the critique being that his act of translation is a performance of his cultural supremacy. In “lovers’ quarrel with abdelhalim hafez,” the speaker goes further: when the character Abdelhalim Hafez informs her that “the words love & wind / sound the same in arabic”—in fact, the speaker first explains this wordplay 52 pages before in “vocabulary,” a poem in the form of a mock multiple-choice test—the speaker calls out his condescension. “Why assume i didn’t already know,” she asks. When Abdelhalim Hafez responds with lyrics, he means to cool off the speaker’s anger and charm her; she won’t have it. She refuses him with an edge to her tone. In what seems a reference to generations of women under Egyptian rule, she asserts, “look i’m a sad girl from a long line of sad girls / doesn’t mean you can talk to me that way.” These moments of doubt on the part of Abdelhalim Hafez in his role as interviewer and moments of self-assertion and refusal on the part of the speaker in her role as interviewee both question and upend colonialism’s dominion over Sudanese identity within the scope of the collection.

In what seems like a thesis to the collection, the poem “why abdelhalim” explains simply that the speaker has chosen the historical Abdelhalim Hafez as the subject of her persona poems because “he can never tell me i am too much or not / he will never think me too / dark or not dark. enough.” This is less a reflection of the singer’s personal politics and more of a function of the reality that “he’s gone / . . . / he’s been dead my whole life.” The implication is that while he is considered a cultural authority, he is also one that in his absence is open to interpretation and reinterpretation across multiple encounters. The construct of these encounters between the persona Abdelhalim and the speaker, in which they adopt interviewer and interviewee roles as well as in moments of departure from these roles, allows for poems like “self-portrait with yellow dress” and “alternate ending”—poems of re-envisioned possibilities—to exist. In “alternate ending,” Elhillo imagines the occasion in which “where i’m from is where i’m from & not / where i was put.” The collection as collage suggests that for the people of the Sudanese diaspora—and perhaps Southwest Asian and Northern African communities more broadly—prerequisites to this vision include reckoning with the colonial histories that influence our sense of cultural authority, the internalized racism inherent to hierarchies in which authenticity-checking flourishes, and the small ways we can begin breaking out of our scripts.