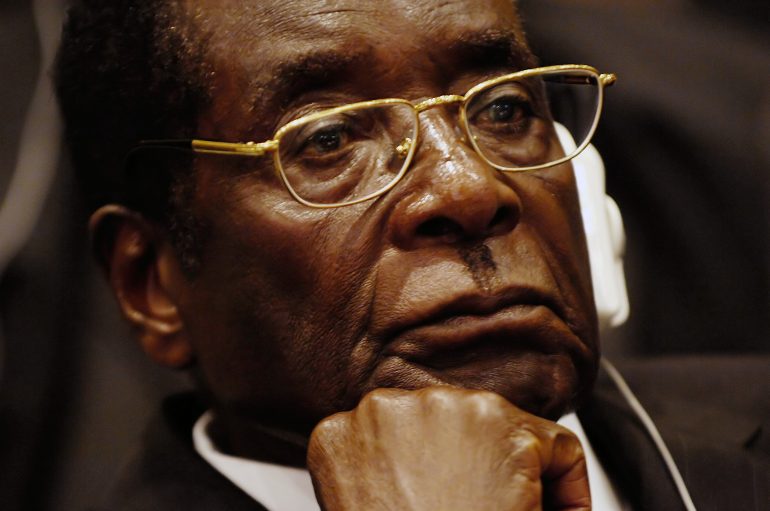

Mugabe’s Shadow in Recent Zimbabwean Fiction

Robert Mugabe’s resignation last month was the most significant development in Zimbabwean politics in a generation. A Zimbabwean acquaintance of mine expressed some of the cautious optimism the country is now feeling when he wrote, “this will indeed usher in a new dimension in our efforts to craft reforms for the holding of free and fair elections.”

One way of assessing the shadow of Mugabe’s brutal hold over Zimbabwe’s history is assessing the shadow he casts over Zimbabwe’s post-independence fiction. This is significant.

Perhaps the best example of this is 2013’s The Hairdresser of Harare, Tendai Huchu’s novel of contemporary urban relationships that manages to be both breezy and serious. For instance, talented hairdresser Vimbai explains her business rationale in a shockingly casual way: “I figured since the country’s average life expectancy was thirty-seven, I would concentrate on the young and the beautiful. There was no point in indulging a clientele that was statistically supposed to be dead.”

The book evokes Zimbabwe’s fragile economic state through a series of vivid details: People queue for hours to receive their wages. It’s a fool’s errand to set future prices, because inflation will soon render the money useless. There are no more pickpockets because no one bothers with wallets anymore; any amount of cash they could have held would be worthless.

First Lady Grace Mugabe (who until Mugabe’s resignation seemed likely to be Zimbabwe’s next president) appears twice in the book as a customer in upmarket hair salons in Zimbabwe’s capital. But if there’s a villain in The Hairdresser of Harare, it’s Minister M___, another politician who, like Robert Mugabe, emerged from the armed independence struggle of the Rhodesian era to gain power when the country was renamed Zimbabwe. And like Mugabe, she profited from tensions between black and white Zimbabweans; in the novel, the minister continues to harass and taunt a white woman, a friend of Vimbai’s, whose farm she’s seized. The minister’s affinity for Mugabe extends to wearing, rather ridiculously, a dress and a head wrap featuring pictures of the president.

The president is also obliquely referenced in a long, self-aggrandizing speech from a wealthy character. This ends, “there are only two men in this country who will never die, and I’m one of them.” A similar sentiment is expressed by the grotesque leader who features in “Election Day,” from Christopher Mlalazi’s 2008 short story collection Dancing with Life: Tales from the Township. This nameless character, who clearly represents Mugabe, calls himself the Incredible Hulk of Africa. As he boasts about the money he’s siphoned away and the hold he has over the country, the others around him are panicking about election results that show the opposition’s clear lead. His Excellency alone is unruffled–and a last-minute bout of vote-rigging shows why he was confident of remaining in power. Of course, following the events of November 2017, Mugabe now looks less invincible.

NoViolet Bulawayo’s beautiful and searing We Need New Names, published in 2014, doesn’t reference Mugabe by name, but again his presence is felt. The children in the shantytown Paradise are very aware, from Zimbabwe’s example, that presidents are old and rich. They turn presidents and war veterans and bulldozing of neighborhoods, like everything else, into a game.

The novel depicts Mugabe’s influence on both people within Zimbabwe and the diaspora that has conflicted feelings about what home and heroism mean. Middle-aged Fostalina, catching sight of Mugabe on the news in her Detroit home, starts “shaking, her face suddenly ugly like she was chewing some thorns.” Fostalina’s trauma is complicated by her Ghanaian husband’s veneration of Mugabe as a liberator from colonial oppression. “Africa’s leading statesman!” he calls Mugabe. The kids in the room are mystified and bemused. But the ambiguity of the moment reflects the complicated nature of what Mugabe represents. Yes, he’s a violent despot who brought the Zimbabwean economy to its knees; yet he also became a symbol of hope and resistance against white imperial forces that had themselves established the precedent for tyrannical, rapacious rule over Southern Africa.

We Need New Names is also piercing as it shows the dangers of pinning hopes on regime change. This is very relevant in the current political moment, in the aftermath of a coup that was orchestrated by Zimbabwe’s military and installed Mugabe’s former vice-president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, in the top seat. In We Need New Names, election day is euphoric, bringing pride and celebration to Paradise. But these hopeful people “stayed up night after night and waited for the change that was near. Waited and waited and waited. But then the waiting did not end and the change did not happen…Now everything is the same again, but the adults are not. When you look into their faces it’s like something that was in there got up and gathered its things and walked away.”

All three books grapple with certain pervasive features of Zimbabwe, which is still a young country: the inequality, the economic disarray, the influence of the diaspora, the tension between colonial and postcolonial influences, and the importance of family and community. Another feature is the looming political presence of the most famous (and infamous) Zimbabwean, Robert Mugabe. It will be interesting to see how Zimbabwean fiction post-Mugabe finds new touchstones for reflecting on allegiance, power, and historical memory.