People of the Book: Stephen Skuce

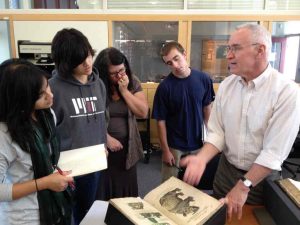

People of the Book is an interview series gathering those engaged with books, broadly defined. As participants answer the same set of questions, their varied responses chart an informal ethnography of the book, highlighting its rich history as a mutable medium and anticipating its potential future. This week brings the conversation to Stephen Skuce, Program Manager for Rare Books at the MIT Archives & Special Collections.

1. How do you define a “book”?

I’m a traditionalist. For me the word “book” conjures up a brilliant piece of technology comprising leaves of paper that usually are imprinted with words or images and meant to be arranged in a particular order. One edge of the paper is typically attached to a binding made of stiffer stuff.

E-books enter the picture if we’re discussing content more than physical form. Of course, you can read a book on a tablet, and there’s no reason not to. But that’s a “book” only in regard to its length and intellectual content. Most of the time when I talk about books my reference is to tangible objects.

2. How do you engage regularly with books, beyond reading?

I’m very lucky: as part of my job, I get to share MIT’s rare books with brilliant, highly engaged students and an astonishing faculty; this is an activity from which I always emerge with new insights. Another learning activity involves book-centered exhibits in our gallery. I monitor the physical condition of the collection and confer with a wonderful conservation staff. I’m also responsible for cataloging the rare book collection, which is more difficult than it sounds. Two copies of a book from the hand-press period may appear to be identical but often are not, and identifying the subtle differences is painstaking work. Then there are the languages: a stack of books on electricity from the 1850s will contain items in French, German, Italian, Spanish, English, and Dutch.

I’m also a collector—not a serious collector, but an obsessive one. I decided I liked Edith Wharton when I was in my twenties and, though broke, began collecting early editions of her works. She hadn’t been widely rediscovered yet, and I made some lovely finds, along with a few nice editions by other favorite authors, too.

3. What has been your most unusual interaction with books?

I’m not proud of it but once performed a temporary furniture repair by shoving a 20-year old paperback copy of Antigone (the Gilbert Murray translation) between the pedestal and the top of my oak dining table, to make it level. I call the repair temporary, but it worked for 15 years till I finally broke down and had the table fixed properly. In my defense, the book was used when I bought it, and in any case, I preferred Elizabeth Wyckoff’s translation.

4. Do you have favorite tidbits from the history of books?

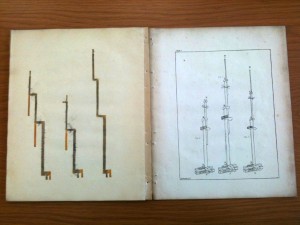

MIT’s copy of W. Snow Harris’s Observations on the effects of lightning on floating bodies (London, 1823)

Because of where I work and the classes I work with, I can devote only a bit of my attention to “book history.” Instead my focus is largely on the intellectual content of the collection. For MIT’s rare books, that generally means a publication’s importance within, or oddness in relation to, the history of science and technology.

Many volumes in our collection are of particular interest because of things that happened to them after they left the printer’s shop: marks are left by owners and readers; corrections and comments show up in the margins; objects are inserted, sometimes by anonymous readers and sometimes by notable figures; authors inscribe books as gifts … it’s the history of books writ small: the “history” revealed within these specific copies.

My favorite tidbits have to do with the history of science as reflected in scientific books that contain post-publication markings. I love the things books can tell us about the human relationships of key scientific figures. An offprint of a paper by Charles Babbage can seem uninteresting until you notice that he’s inscribed it, in ink, to André-Marie Ampère: these are intellectual titans communicating directly with one another, and such things fascinate people at MIT who are familiar with the accomplishments of both individuals.

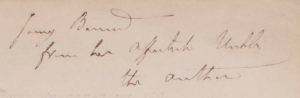

Sometimes the material is poignant. We have many items that were owned or inscribed by the great 19th-century scientist Michael Faraday. One of my favorites is an offprint of a paper concerned with the effect of heat on the magnetic force of bodies. Most of the items Faraday signed were addressed, unsurprisingly, to other scientists. This one, though, is inscribed to his beloved niece: “Janey Barnard, from her affectionate Unkle the Author.” It hints at a lovely bond between a woman and her aging uncle, a relationship that combined pet names (“Unkle”) with arcane scientific offprints given as gifts. A dozen years later, Jane Barnard—his “Janey”—would be holding Faraday’s hand as he drew his final breath.

Your typical rare book repository has many inscribed treasures; MIT’s holdings are not unique in that way. But we all have a pretty clear idea of how William Wordsworth felt about, well, absolutely everything: he wrote it all down in verse and published it. That is not the case for scientists from the 19th or any other century, no matter how famous they are: the work that brought them fame was about everything except their personal lives and feelings. So material that provides even a glimpse at the human side of a scientific giant can resonate powerfully for people at MIT.

5. What material part of the book interests you most?

Materials for student bookbinding workshop in MIT’s Conservation Lab (with conservator Ann Marie Willer)

The sewing. I don’t know why, but it’s always delighted and comforted me to know that books, or at least well-made books, are sewn together with thread.

6. If your house was burning and you had to take three books, which would you save? Why?

My first edition of E.M. Forster’s Two Cheers for Democracy, because he’s an idol of mine and because the book’s understated design makes it the perfect vehicle for beautiful essays by a master of tone.

I’d want to save one of my Whartons. Maybe Summer, even though a houseguest (notice I didn’t say “friend”) used my copy as a coaster for his drink, ruining the cover. But I’d still rescue it because it’s the sexiest thing Edith Wharton ever wrote. Seriously.

I’d want to save one of my Whartons. Maybe Summer, even though a houseguest (notice I didn’t say “friend”) used my copy as a coaster for his drink, ruining the cover. But I’d still rescue it because it’s the sexiest thing Edith Wharton ever wrote. Seriously.

Finally, I’d run to the piano and grab the Fireside Book of Folk Songs, a gift from my Auntie Vi in the 1990s. Her eyesight had failed and she could no longer read the notes or see her keyboard. Vi was well into her 80s, and she gave it to me because she knew that my partner—now my husband—played the piano, so she wanted him to have it.

7. What about the current moment for books interests you?

How about something that angers me: the poorly edited books coming out of major publishing houses. They’ve just got to pay for decent editing if they want to feel superior to the blogosphere. Typos happen, I know, but I’m talking about howlers. How could an editor with a functioning frontal lobe miss a line like this, from a book I read in 2008: “You can’t underestimate the impact that the Club of Honest Whigs had … ” The author meant that the Club had a powerful impact; he meant to say “overestimate” or “overstate.” It’s one thing to use an imprecise word; it’s another to use the antonym of the word you wanted. This specific error is both common and commonly decried, which makes its appearance in print even more egregious. I realize I’m carping, but this stuff actually interrupts the act of reading.

8. Where do you go to find and/or give away books?

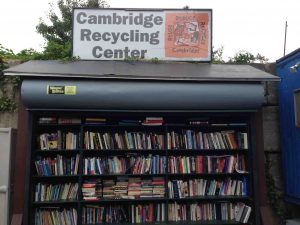

For new books, I walk to the Harvard Book Store, and if they don’t have what I want, I let them order it for me. No Amazon, period. For used books it’s serendipity or a search of some good used bookstores. To thin my collection, I drop things off at Cambridge’s recycling center, which has a nice “sharing wall” for taking or leaving books.

9. How do you foresee books evolving in the future?

I have no brilliant insights, but as a librarian I pay close attention to the massive changes taking place in publishing. I’m very hopeful about our faculty’s strong affirmation of open access, and the effort to break scholarly publishing’s stranglehold on the output of our scholars and scientists. I’m also watching the way mainstream publishers treat public libraries trying to circulate e-books. It hasn’t been pretty. The relationship between publishers and libraries, which for a century had been collegial and mutually beneficial, is now heading for the crapper. If that relationship becomes purely antagonistic, I will not blame the libraries.

10. What question do you wish that I had asked related in some way to books? Ask, then answer it.

- Q: Why does MIT even have rare books? Why would people in such a place be interested in such legacy technology, and outdated information?

-

A: The printed book’s pride of place in intellectual history remains obvious even in an institution as forward-looking as MIT. William Gilbert’s De Magnete, printed in London in 1600, is a major scientific landmark, and when I show the book to classes in geomagnetism, the students are already aware of Gilbert’s brilliance, the things he discovered and the ingenious ways he discovered them. But they’re intrigued by the object itself: the title page, the evocative illustrations, Gilbert’s novel use of the asterisk. Something ineffable happens. The physical presence of that 400 year-old volume strikes a chord; its immediate proximity provides a vital connection to its author, and to a centuries-long continuum of scholars unraveling the mysteries, and multiplying the uses, of magnetism. The urge simply to touch the object itself is very strong, and touching is permitted. The topic under discussion may be purely scientific, but the sensation can be strangely emotional. MIT students, whether graduate or undergrad, are not easily impressed. But I love looking on as they examine the binding, or run their fingers across a line of text so they can actually feel the way the type bit into the paper. Our copy didn’t belong to William Gilbert, but it’s “Gilbert’s book” in a way that a modern reprint can’t possibly be.

______

Stephen Skuce is the Program Manager for Rare Books at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As a member of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries, he’s involved in the development of standards for the description of rare printed materials. He was an editor of Descriptive Cataloging of Rare Materials (Serials), published by the Library of Congress in 2003. As an adjunct at the Simmons College Graduate School of Library and Information Science, he taught information organization for several years. At MIT, he oversees the Libraries’ rare book collections, which comprise 40,000 volumes spanning the 15th through the 20th centuries.