The Infinite Library

“I prefer to dream that the polished surfaces feign and promise infinity . . .” —Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel”

You walk through the front doors of a building that resembles more a contemporary art museum than a repository of books. Instead of a librarian at a front desk, and rows and rows of bookshelves in the background, you are greeted by a few sleek, white tables, all littered with electronic devices. High-definition screens surround you on every wall.

You may ask yourself, have I walked into a library or the new Apple store?

Welcome to North Carolina State University’s new state-of-the-art James B. Hunt Jr. Library, which opened this past January. Tour the facility and you won’t see many books; most of its 1.5 million volumes are packed into dense storage, accessible only by a retrieving robotic system called the bookBot. Instead of browsing an actual bookshelf, you interact with a virtual shelf compiled by subject matter.

The concept of an interactive, digital-only library isn’t new; the seed was planted over a decade ago when the Santa Rosa Branch Library in Tucson, Arizona, offered a digital-only library. Last month also saw the launch of the Digital Public Library of America, a set of linked, accessible, digital materials from libraries, archives, and museums around the country. And a new library opening this fall in San Antonio will resemble Hunt Library’s front entrance; patrons there will be able to check out e-readers for home use for two weeks. As Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff told NPR, “The library is a chance to expand the scope of opportunities for people to learn technology. The world is changing.”

The Library As Commons

Should the library change with the rest of the world? Looking through Robert Dawson’s Public Library: An American Commons, which consists of photographs of hundreds of public libraries in the United States taken over seventeen years, I can’t help but wonder. First off, the library has always been more than just a room full of books. As Design Observer’s Josh Wallaert agrees,

The modern American public library is reading room, book lender, video rental outlet, internet café, town hall, concert venue, youth activity center, research archive, history museum, art gallery, homeless day shelter, office suite, coffeeshop, seniors’ clubhouse and romantic hideaway rolled into one. In small towns of the American West, it is also the post office and the backdrop of the local gun range. These are functions that the digital public libraries of the future will never be able to recreate.

However, I must disagree with Wallaert’s last sentence; a digital-oriented library can do all this and more. Not only would it make more books accessible to a wider group of people, but its space could be repurposed for work, study, or collaboration. Indeed, the Hunt Library already has nearly one hundred work spaces, as well as rooms dedicated to high-end gaming and a reconfigurable Visualization Lab that can create an immersive environment—such as a virtual bridge of a warship for ROTC students.

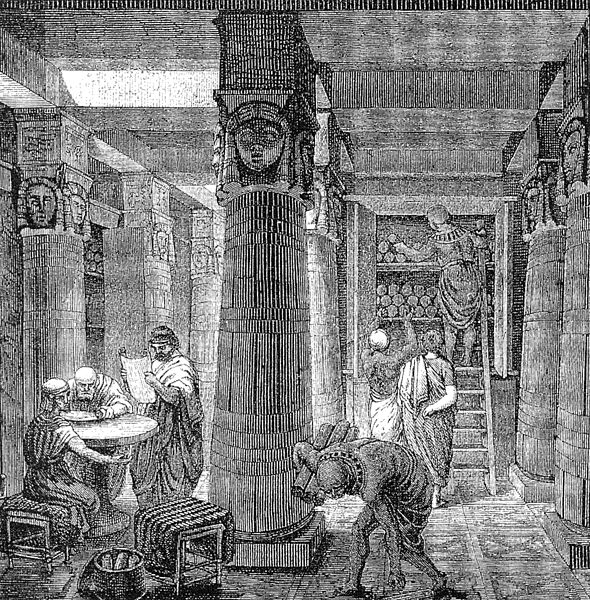

I think the more broad question to ask is: what is the purpose of the library? As I mentioned before, the library is much more than a repository of books; it’s a place to inspire. It is with good reason that we remember the Library of Alexandria today as a fulcrum of intellectual curiosity and invention. Just as libraries modernized with the invention of printing, why can’t libraries today enjoy another, digital renaissance?

“Inevitably, if you invite people in or make something available to people,” Reanimation Library’s founder Andrew Beccone told me last fall, “they’re going to come and do things you’d never expect or dream of.” Similar to DPLA’s Wikipedia-style model, there is a sense of openness or the unknown with digital libraries, and places like the Reanimation Library, located in Brooklyn, New York, offer forgotten and discarded volumes a second chance at life. “I suspected that other people would be interested in the collection,” Beccone told our own Nora Maynard last month, on his decision to turn the library into a public collection, “and that they would use it in ways that I wouldn’t.”

The Commercial Library

Undoubtedly, digital libraries are good. The search for a particular item will always be easier, and an infinite amount of information will be available (licensing agreements aside) to all humans, twenty-four hours a day, no matter where their location. As historian Robert Danton commented, “What could be more pragmatic than the designing of a system to link up millions of megabytes and deliver them to readers in the form of easily accessible texts?”

And that’s why libraries exist: to get books—and other forms of knowledge and entertainment—to readers, provided for free. What, then, could be lost in such a technical innovation? For one thing, there’s our ability to browse, to wander the seemingly endless rows of bookshelves in search of a book you didn’t yet know you wanted to read. More importantly, though, we also stand to lose control of our content.

When the concept of a digital library emerged in the early 1990s, researchers largely ignored the profound cultural, economic, and political impact digitizing books could have. The rise of Web 2.0 has seen an explosion of interaction and collaboration between users in virtual communities; it’s no longer a question of viewing content but instead how content can be used.

And because of this evolution, the enduring, well-documented challenge facing digital libraries is copyright. The future of the public library—both physical and digital—will hinge on how we will be able to purchase content and who will control content. Content is, and always will be, commercial, and in the digital world you will never have complete control over these millions of megabytes. (Just look at Amazon and George Orwell for a reminder.)

There is a lot to gain with digital libraries, but with them comes the risk that freedom of information will be lost. So at least for the near future, we should take care that digital libraries don’t replace traditional ones, and instead remember that they’re just a means to a different end.