“It’s A Bit Mysterious, and I Like That”: An Interview with Frank X. Gaspar

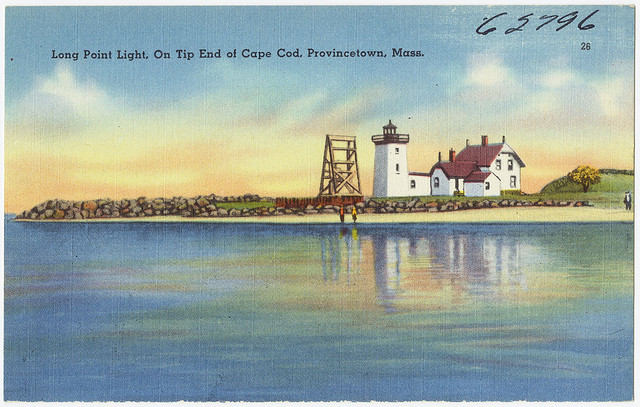

Frank X. Gaspar writes poems that are lyrical, powered by swift associations, and full of surprising images and leaps in thought that in retrospect make perfect sense. He is the author of five collections of poems, including Late Rapturous and The Holyoke, as well as two novels, most recently Stealing Fatima. Frank was born and raised in the old Portuguese West End of Provincetown, Massachusetts. He teaches in the MFA Writing Program at Pacific University, Oregon. We recently caught up via email to talk about Late Rapturous, the strange ways in which a poem can start, and the differences between writing poetry and fiction.

Frank X. Gaspar writes poems that are lyrical, powered by swift associations, and full of surprising images and leaps in thought that in retrospect make perfect sense. He is the author of five collections of poems, including Late Rapturous and The Holyoke, as well as two novels, most recently Stealing Fatima. Frank was born and raised in the old Portuguese West End of Provincetown, Massachusetts. He teaches in the MFA Writing Program at Pacific University, Oregon. We recently caught up via email to talk about Late Rapturous, the strange ways in which a poem can start, and the differences between writing poetry and fiction.

Matthew Thorburn: Late Rapturous is composed of prose poems as well as poems in long lines that sometimes seem on the verge of becoming prose poems. Would you talk about how it feels to you writing prose poems versus lineated poems? Do the two offer different possibilities or challenges?

Frank X. Gaspar: Interesting that you ask that. I don’t feel any difference in the process; it seems more a matter of how my mind is working at the time. I pay as much attention to sound in the long-lined poems as I do with poems having more traditional line breaks—a lot of attention, actually—but without the line breaks to perhaps reinforce the sound with the eye, the prose poems might not announce their accentual nature.

When I begin writing any particular poem, I have no idea what mode it will come forth in. The last few poems I have written are in shorter lines—they just seem to come that way. I let the poems push me around after a point; they seem to know how and where they want to go.

MT: I’m struck by the way your poems can seem to move forward by association, sometimes with an air of improvisation, yet they also feel inevitable to me—as if the poem is saying exactly what it needs to say. How does a poem start for you? And what is your writing process like?

FXG: I heard Allen Ginsberg once say, “Write your mind.” He went on to explain that he found doing so was more helpful and authentic than sitting down “and trying to make something up.” That resonated with me and I tried it, and it has been my modus operandi ever since.

A good number of my poems start with my centering myself right where I am. Sometimes I leave that centering process right in the poem: “I’m hoeing in the yard…” for instance. But in terms of improvisation, I just follow my mind. I had been reading the Dead Sea Scrolls at the time of writing that, so that was in my mind, and it went into the poem. And so on. The poem is “Paradise” from Night of a Thousand Blossoms, and it went into Paradise through Dante and Beatrice. I didn’t make it up. These thoughts were playing on different tracks in my mind. So I listened and watched.

This is not to say these things come out right—there is often a great deal of drafting. It’s not unusual for me have a twenty-line poem come out of two or three filled pages.

MT: I became aware of your poems by reading your recent work in Miramar, a journal that consistently amazes me, so I wanted to ask: are there journals that you especially turn to as a reader? And what have you read recently that moved you?

FXG: I am just looking around on the floor of my study: Miramar, of course, and Kestrel, and december, and Natural in Verso, which is a bilingual collection published in Lisbon. I have always loved The Georgia Review, Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner—and many others. Too many to include. When I get around to sending poems out, it’s always to magazines that ask for them or magazines that I like. The categories overlap somewhat.

I spend a lot of time going back to masters—Emily Dickinson, Hart Crane, Fernando Pessoa, for instance. I just finished a biography of Anna Akhmatova which moved me tremendously. It is rich with inclusions of her poems, and it gives a wrenching yet heroic look at her life and art, and the role of poets in Russia from the Revolution through the years of Stalin’s Terror. Poets in that culture were venerated, and many suffered horrifically for not toeing to party lines. It’s given me much to consider as we go forth in our own age and consider the imperatives and obligations of what we write.

MT: What are you working on now?

FXG: A very cranky novel. Cranky meaning it seems to demand being treated on its own terms. It makes me change everything as I go, and it really wants to run off and marry a poem. I only write both novels and poems because there is something irremediably wrong with my common sense. But I can’t help myself in this regard.

Generally I can’t work on poems when I am writing on a novel and vice-versa. This is not a good thing. Some new poems have managed to creep in through the cracks—slender ones, by the way, and in someone’s voice that is very different from what I consider to be my own. I hope they keep coming. It’s a bit mysterious, and I like that.

Read three poems from Late Rapturous here.